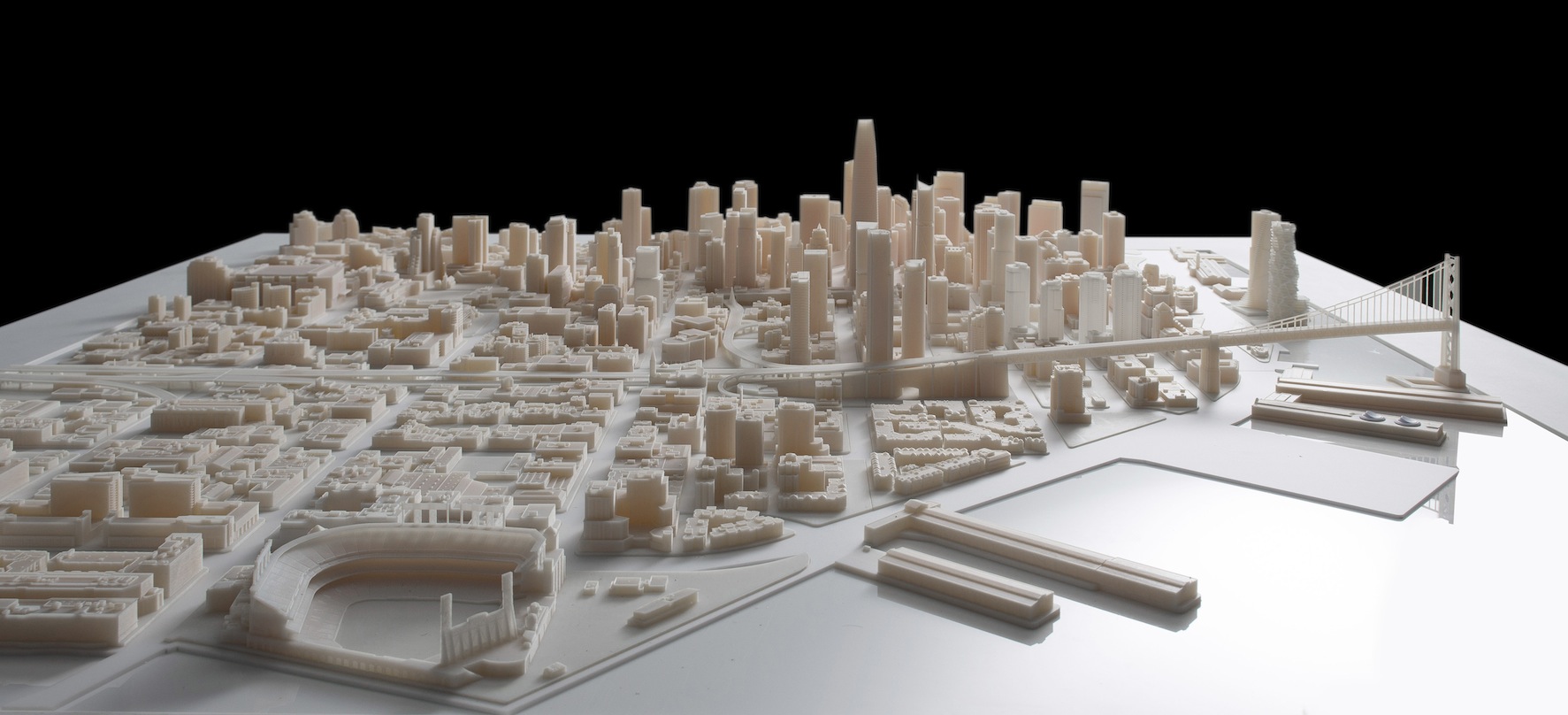

Much like the human body with its skeletal, cardiovascular and nervous systems, cities have infrastructure systems, such as highways, water systems and communications systems that allow people to move about the city, deliver goods and services and share information. But as we’ve seen recently, these city infrastructures often collectively fail during man-made and natural disasters. Why? Unlike the human body, these systems are often developed in silos, over time, in less-than-perfect ways. They are typically built for normality, not adaptability. As a result, there is no guarantee — often no real plan — that they work well together when subjected to a shock like flooding, a large earthquake, a heat wave, or a long-term stress such as explosive population growth and ensuing congestion.

The way these systems become interdependent can make a city brittle, and it means that in a disaster, a failure in one system quickly cascades to the next. For example, metropolitan water is used for drinking, but also for local agriculture and power generation. A drought that severely constrains water means that water for human consumption must become a priority, but that can lead to a loss of water for agriculture, as California is now experiencing, and power generation. To combat these water cascades (no pun intended), cities must not think about water systems without also thinking about food and power systems. As with the human body, each of these systems is semi-autonomous to capitalize on its specialized function, but will fail – now or in the future – if it can’t rely on the other systems. Hold your breath for a minute and think through all the system cascades your body will go through – aerobic, circulatory, muscular, nervous system – to adapt to the loss of just one system. The difference is your body has evolved this adaptive ability; many cities have not.

Infrastructure systems cascade during disaster, lead to more disruption

There is no shortage of real examples where infrastructure systems cascade during disruption:

From our partners:

- After Superstorm Sandy, impassable roads led to inability to restore electric power. That led to an inability to fuel cars and trucks due to flooding and a lack of electricity to pump fuel. That cascaded into further economic impacts, as people were unable to get to work.

- In the 2011 Fukushima earthquake and tsunami, flooding of backup generators caused overheating of fuel and nuclear release.

- During Hurricane Katrina, few believed that the levies would break, and when they did, the massive flooding caused loss of human life and ran roughshod through emergency response, medical care, water and wastewater systems and transportation services.

- The Northeast Blackout of 2003 caused boil-water orders and widespread cellphone outages, causing illness and hindering emergency response.

- A 2012 power outage in India left 600 million people without electricity, disrupting water supply, stalling hundreds of passenger trains, and stranding 200 miners (some blame this failure on India’s explosive growth).

As a result of these system failures, lives are deeply, often permanently changed; many businesses disrupted by these disasters never return.

The bottom line is that from a resilient-city policy point of view, it’s not enough for water, electricity or fuel systems to be resilient to shocks. The linked water-electricity-fuel systems need to be resilient to these shocks.

So, what can cities do?

- Design or redesign: Cities need to design – mostly redesign – their systems for resilience, that is, so that they can continue to deliver services in the event of a shock or acute stress. New York State, for example, now requires that a certain number of gas stations in each locality have backup generators so that a power outage doesn’t prevent people from fuelling their cars.

- Analyze interdependencies: Getting to resilient designs will require better understanding – through analysis – of what these interdependencies are. Which infrastructure are most important for near- and long-term resilience? What infrastructure risks – loss of electricity, transportation or emergency response – most jeopardize the city’s people-resilience goals and why? What interdependencies between these systems could cause shocks and stresses across these systems, affecting the resilience of them all? And what are the benefits and costs a particular resilience design buys a city?

Metrics for cities on the way

Resilience analysis will require risk assessment and resilience measurement. As we speak, metrics are being generated: a recent Suisse Re study estimates city risks to natural disasters; a recent Grosvenor study takes it one step further by analyzing cities’ resilience based on their vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities. The latest C40 Report outlines climate adaptability metrics and design approaches for 63 member cities. And cities can utilize advanced techniques, such as scenario planning in conjunction with options analysis, to address not only climate and other future uncertainties but also what adaptability cities can put in place to be resilient to that uncertainty.

Smart growth – literally, being smart about city growth – can generate a resilient future if cities tame these increasingly ungainly infrastructure systems, through analysis and then resilient design or redesign, and implement these designs through city planning, investment, and coordination. Designing infrastructure for resilience can be done while designing for growth. Individually and collectively these systems can and do serve us well – even thrive – during growth, stress, and shock. And even during everyday life.

OK, you can stop holding your breath and let your systems recover.

This article originally appeared on 100 Resilient Cities.