It took very concerted policy efforts going back to the early 1990s.

If you’re a city resident of a certain age—basically, that part of the generational Venn diagram where X and Y overlap—you probably know someone who recently left to start a family. The reasons vary, but in predictable fashion. Not enough room in the apartment. Not enough park space nearby. No dependable public school and no affordable private one. No way to navigate a stroller on the subway that doesn’t result in occasional tears of rage.

But are cities fundamentally unsuited to family life, or have they been in such a rush to feed the needs of young singles that they’ve unwittingly overlooked the procreating part of the population? The Sightline Institute’s blog has been running a fantastic series, written by Jennifer Langston, tackling these very questions. All the posts are worth a read, but what caught my eye was one on a North American city that seems to be doing an especially great job luring families: Vancouver.

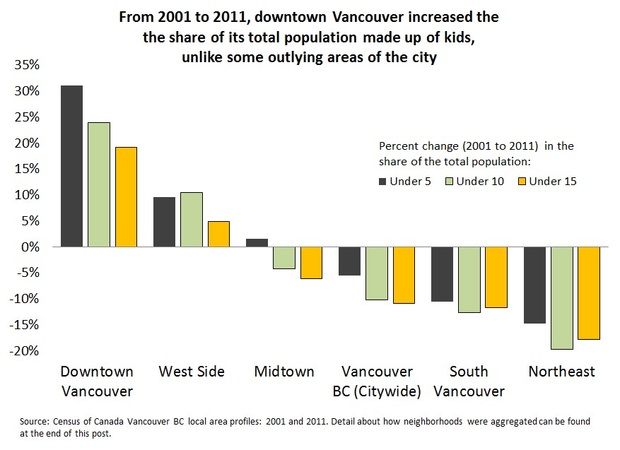

Downtown Vancouver, in particular, has made a concerted effort to improve living conditions for families, starting back in the early 1990s. Evidently, the policies have paid off. In 2011, downtown Vancouver was home to 5,100 kids under 15—five times more than downtown Seattle, which itself is doing better in this regard than most American cities. This part of Vancouver is also outpacing the city at large, as well as outlying parts of the metro area.

From our partners:

Let’s take a closer look at the policies responsible for this change (most of them described in a set of guidelines for “high-density housing for families with children” adopted by the city in 1992).

Units: For starters, Vancouver required developers to set aside of share of high-density housing units for families—typically 25 percent, according to Langston. That means at least two bedrooms, one of which should have play space for toddlers designed into it. (Oh, and thick, thick walls.) Since families might not want to live on the 16th floor, the city suggested grouping family units closer to street level, often in multilevel townhouse-type structures that form the base of more traditional residential towers. This ground-level clustering makes coming and going easier and gives children peers in neighbouring units.

Buildings: Family-friendly buildings need a few architectural quirks that towers for singles might not: bulk storage space for things like strollers or toys, better nighttime lighting in common areas, corridors that can fit a tricycle. They also need secure, safe play spaces—ideally ones that can be seen from inside the units or from a designated supervision area. The spaces should maximise sunlight and be made to withstand “the rough and tumble of children’s play,” according to Vancouver’s guidelines. You have to love a government document with lines like this: “Opportunities for water and sand play are especially important.”

Surrounding areas: Vancouver also realised that not all parts of the city were as family-friendly as others. It instructed developers to choose sites within half a mile of elementary schools, daycare centres, and grocery stores, and within a quarter mile of transit stops. Safe walking routes—ideally separated from high-traffic arterials—were also important. Langston writes that the city went a step further and actually required some developers to build or fund community facilities (such as daycare centres or parks) if none already existed, and even to designate sites for schools.

One former Vancouver planner told Langston that developers might initially balk at such requirements, but that they’d eventually recognise the potential to reach a new market. Indeed, a follow-up study on housing satisfaction among families in the city’s False Creek North area found that 96 percent would recommend living there. The conditions aren’t family-perfect—the city still has a shortage of schools, space for teenagers has been tougher to create, and questions of affordability linger—but they’re definitely family-friendly.

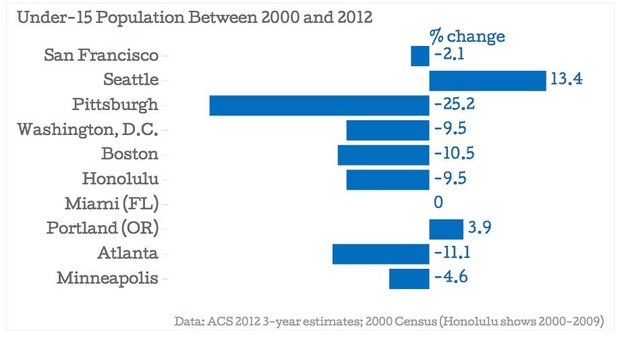

Using Census data, we reexamined this list by change in population of kids under 15 (not 18) between 2000 and 2012:

What does this show us? First and foremost, that many major U.S. cities have their work cut out for them if they want to be home to more families. Those that do can’t start implementing such policies soon enough. But it’s interesting to note that the two cities on this list actually growing their youth population, Seattle and Portland, are also the ones closest to Vancouver. Coincidence? Perhaps. A good place to set the family-friendly compass? Sure seems like it.

This article originally appeared in CityLab.