Psychologists still don’t fully understand driving-related violence. But technology and improved transit infrastructure offer solutions to minimise it.

When Evander Holyfield was a young man, he was the victim of road rage. He was 17, he tells the Associated Press, and driving a car he described as “raggly.” When it broke down suddenly in the middle of the road one day, it set off an older driver, who honked his horn, furious, and even left his car to confront the future Undisputed World Champion boxer. Even at that young age, Holyfield was already an amateur champion. This is the Real Deal we’re talking about.

Fortunately for the other guy, Holyfield kept his cool.

Drawing on his early experience, the heavyweight boxer is now starring in a new public service announcement about road rage produced by Georgia law-enforcement agencies. In the video, Holyfield pulls out of a tree-lined driveway in his luxury SUV, only to cut off some bubba in a raggly Ford pickup truck by accident. Things don’t go bubba’s way.

From our partners:

“Everyone knows Evander Holyfield,” Georgia Attorney General Sam Olens told the AP. “Everyone knows he’s a former four-time heavyweight champion. And everyone knows they don’t want to mess around with him.”

Fair enough: Avoid fighting Evander Holyfield. (And whatever you do, do not get into a traffic run-in with Mike Tyson.) But what good does this message do for drivers? And what does it really say about violent or aggressive driving?

Vehicular assault, fist fights, stabbings, shootings: If the evening news is any indication, the nation’s drivers are out to get you. Yet 20 years after road rage emerged as a concern, the core reasons for violent frustration behind the wheel remain poorly diagnosed. Looking back, the phenomenon seems both overblown and understudied.

A national epidemic—or a ’90s media trend?

In a 1998 article for The Atlantic, Michael Fumento registered a surge in reports on behaviour the public was calling “road rage.” The phrase was coined a decade earlier, by newscasters at KTLA in Los Angeles, following a series of freeway shootings. Road rage didn’t take off in headlines and scare stories, though, until 1994.

“‘Road rage’ replacing DWI as top problem,” reads a typical headline in The Star-Ledger in 1997. “Nationally, there is an epidemic of ‘road rage’—aggressive drivers running red lights and venting high-speed hostility toward other drivers, the law and perhaps toward the hand that life has dealt,” offered George Will, in a 1998 column for The Washington Post.

Causes for road rage abounded. In a 1998 interview with The New York Times, John Larson, the late founder of the Institute for Stress Medicine in Norwalk, Connecticut, and author of Steering Clear of Highway Madness, blamed Hollywood. Larson specifically indicted a movie from the 1980s he called Road Warriors (perhaps referring to the 1981 post-apocalyptic classic, Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior).

Larson also blamed road rage on advertising and high-performance vehicles. He wasn’t alone in reaching for reasons. In his 1998 Post column, Will pinned road rage on identity politics and political correctness.

Fumento wasn’t buying any of it. His Atlantic article debunked the handful of studies and polls that served back then as evidence for an epidemic. As far back as 1998, he was condemning road rage as too broad a category, one that had expanded beyond driver-on-driver assault to include fights over parking and other conflicts. “The definition of ‘road rage’ now requires neither a road nor rage,” he assessed, four years into the so-called epidemic.

No data could confirm an increase in the incidence of aggressive driving, Fumento concluded, except for the increased number of people noticing and talking about it. “How many more lives could be saved and injuries prevented if we focused on behaviours that cause accidents, rather than on media creations like road rage?” he writes.

History has partially vindicated him. The number of screaming headlines describing road rage appears to have fallen off sharply. In fact, a Lexis search for stories in recent years containing “epidemic” and “road rage” garnered many more false positives than authentic hits. For example, a columnist for the Montgomery Advertiser offered in October that Ebola should rank low among epidemics in the U.S., a semi-serious list including “gun violence, road rage, high speeds, high places, global warming, memory loss, and weight gain.”

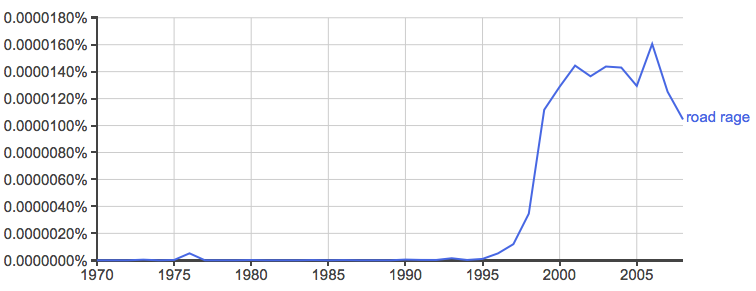

A scan of Google Books confirms the surge of road-rage interest in the 1990s, its plateau in the 2000s, and its relative decline since.

Yet road rage didn’t fall off the map altogether. Anti-road-rage advocates, most notably the clinical psychologist Arnold Nerenberg, pressed the American Psychiatric Association to include road rage as an entry in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. While the ever-growing DSM had listed “Intermittent Explosive Disorder” as a thing since the third edition (1987), only through subsequent revisions (in 1994, 2000, and 2013) did the definition for IED expand sufficiently to capture road rage. Domestic violence is also sometimes categorised under the same anger disorder.

For his part, Nerenberg—who once maintained a website at roadrage.com, and sold his guide, The Handbook for Overcoming Road Rage, via a toll-free number, 1-888-ROAD-RAGE—was convicted last February for defrauding the federal government of nearly $1 million.

Working through road rage, clinically speaking

Aggressive driving, of course, never went away. But despite its quasi-official designation as a ubiquitous mental disorder, road rage is the subject of some pretty thin research.

For example, a study from Plymouth Rock Assurance released last September found found that 99 percent of surveyed licensed drivers in New Jersey had witnessed at least one road-rage incident. Yet only 35 percent of these drivers reported feeling “uncontrollable anger” themselves while behind the wheel. Maybe typical of bad driving studies, but not at all isolated.

More rigorous, less subjective analyses are out there, including a 2006 study released in Accident Analysis & Prevention on the groups of people who were more likely to engage in road rage. (Namely, it’s the usual suspects: men, young adults, binge drinkers, people with trust issues, people arrested for non-traffic violations, and—worryingly—motorists with a gun in the vehicle.)

“Despite the fact that IED, or some version of this diagnosis, has always been included in the DSM, changes in criteria in the various editions over the years have resulted in relatively little being known about the incidence or prevalence of IED either in clinical samples or in the general population,” reads a 2007 survey from the Archives of General Psychiatry. At that time, only two prior published studies had grappled with the epidemiology of impulsive aggression. The 2007 survey concludes, in summary, that “IED is a much more common condition than previously recognised.”

“While road rage is an intuitively recognised phenomenon for most of us, for research purposes, a consistent definition of the term appears to be lacking,” ventures a 2010 report in Psychiatry. This study found that just 2 percent or fewer incidents of road rage ever result in physical damage to person or property. Even still, the actual figures for violent crimes might still be strikingly high, depending on the definition of road rage and whether it includes things like fisticuffs over parking spots.

Research that takes a step back can be illuminating. An experiment detailed in Environment & Behavior found that exposure to roadside vegetation (as opposed to manmade materials) can lead to higher tolerances for frustration among drivers. Mood and the presence of passengers plays a role in a teenage boy’s willingness to engage in risky driving, explains a study in Transportation Research. These are efforts to understand complex driver behaviours, which might be more fruitful than approaching road rage as an epidemic.

Still, the problem is diffuse, according to the government. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration distinguishes between aggressive driving (a traffic violation) and road rage (a criminal offence). Of some 6.8 million automobile accidents every year, NHTSA attributes “a substantial number” to aggressive driving. That’s as specific as the agency gets, though.

One solution for road rage: Ban all drivers

Experts appear to agree that road rage—to the extent that it exists outside of 1990s alarmism—is a catch-all term for complex psychological and environmental factors. Some of those psychological contributors include displaced anger, unrewarding jobs, and an inability to accept blame, according to relevant research. Those are tough nuts for policymakers to crack.

Among the environmental factors, though, are some areas where smart planning and legislation could make a difference in driver behaviour. The number of miles driven per day, traffic density, and the presence of a firearm in a vehicle all appear to contribute to aggressive driving. Getting guns out of cars seems like a no-brainer for eliminating deadly driving conflicts (even if it’s a non-starter politically).

Pulling drivers out of cars altogether might be another solution. The jury’s still out on how or whether this could work. Even with the imminent opening of a testing district in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and ongoing tests in Mountain View, California, driverless auto technology is still far from a proven technology. It’s not entirely clear yet that driver-free automobiles will improve the experience on the road. They might just make traffic that much worse. (For Google’s part, its self-driving machines won’t be designed to rage against us.)

Laws on aggressive driving are all over the map. In Virginia, aggressive driving is a separate (and lesser) offence than reckless driving. Several other states have passed sanctions targeting aggressive driving. California law specifies that courts can suspend the licenses of drivers who commit criminal vehicular assault.

More states should follow the lead of New Jersey, which passed an expanded assault-by-auto statute in 2012. Under the law, drivers who cause injury for reason of anger are subject to the same severe penalties as drivers who cause harm while under the influence. The growing prevalence of dash-cams (or bike helmet-cams) makes motive easier to establish.

If a solution is in the offing for violence related to aggressive driving, it’s probably going to come from the technological or legal sphere, not better mental-health treatment. And any solution is likely going to need to address environmental factors that guide fundamental driving behaviours—factors such as traffic planning, speed limits, segregated bike lanes, and so on.

Perhaps nothing can solve road rage. But if violent crimes arise from conflicts that are built into street design and traffic planning, those crimes are preventable.

This article originally appeared in CityLab.