In exclusive Malabar Hill, the city’s dwindling Parsi community continues with the Zoroastrian tradition of disposing of dead bodies by exposing them to scavenger birds. How much longer can this 3,000-year-old tradition survive?

The price of homes on Mumbai’s swanky Malabar Hill would make Manhattan blush. The current rate soars to a dizzying Rs 100,000 (£1,000) per square foot. But a verdant sprawl of 54 acres on the hill’s crest is not available for money of any heft or colour. Here, shrouded in mystique and ancient trees, the ‘Towers of Silence‘, or dakhma, repose in the 300-year-old Doongerwadi, the garden on the hill. Here, the city’s once-definitive, now-dwindling Parsi community continues with its 3,000-year-old Zoroastrian tradition of disposing of the dead body by exposing it to scavenger birds.

The prophet Zarathushtra insisted on a reverence for all elements. None of them is to be defiled. A corpse is considered impure not just physically on account of infection and decay, but also because it is swiftly colonised by evil spirits. Therefore, cremation and burial on land or sea are unacceptable. However, in places where no dakhmas were possible – Delhi and the Diaspora for example – the dead are interred in community plots in Christian cemeteries.

Keeping aside the macabre imagery, this system of exposure known as dokhmenashini is swift and ecologically sound. It’s also softened by mythology: the soul’s cosmic transition is aided by the vulture’s mystic eye, and the feeding of one’s dead body to the birds is considered the devout Zoroastrian’s final act of charity.

Dokhmenashini originated in ancient Persia, the homeland which the Parsis fled, circa 900 AD, to protect their ancient faith from an emerging Islam. The practice survived in pockets such as Yazd, but Iran’s dakhmas were declared a health hazard and illegal in the 1970s because urbanisation had marched upon these once-desolate ‘sky burial sites’. Mumbai’s Doongerwadi broods on despite its luxe location. But the towers are now far from silent.

From our partners:

The threat hasn’t come from the health department of the municipal corporation or external protest. It has arisen from the dokhmenashini system’s chief accessory. India’s vulture population had seen a steady decline due to habitat destruction caused by that omnibus aggressor, urbanisation. But it precipitated thanks to the livestock version of the drug Diclofenac, developed in the early 1990s. It proved toxic for the vultures feeding on bovine carcases. The drug was banned in May 2006, but by then it had decimated 95% of these birds. And plunged the towers of silence – and an aging community – into seismic controversy.

It’s epicentre is Mumbai where 45,000 of India’s 61,000 Parsi-Irani Zoroastrians live. The ratio of deaths to births is 3:1, so deep faultlines appeared after a woman called Dhun Baria produced ghoulish photographs supposedly of unconsumed corpses piled up in the dakhmas of Doongerwadi. This was doubly disturbing for a community whose ancient funereal ceremonies lay great store by ritual purification and distancing the living from the ‘contagion’ of a corpse. The dead can be handled only by a designated class, who by this token became the ‘untouchables’ of an otherwise proudly casteless community, a marginalisation portrayed in Cyrus Mistry’s unsettling novel, Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer.

Parsis are an exemplary minority in an India of inter and intra-communal strife; they are lovably eccentric and heir to the awesome legacy of their forebears who created much of Bombay’s wealth and built visionary institutions. So, cocooned in the goodwill they enjoy, they are left very much to their own practices. It is difficult to imagine a similar benign indifference to an inefficient disposal system in the heart of as posh and powerful a residential area as Malabar Hill, even if it remains out of sight within a 54-acre cordon sanitaire.

After Baria’s photographs, an agitated section of Parsis themselves demanded a municipal inspection, an idea abhorrent to traditionalists since non-Parsis are allowed only in the peripheral areas of Doongerwadi. However the ambient air was swiftly examined, and declared safe. But the disquiet has not disappeared. How can it?

A project in collaboration with Oxford University to breed native vultures in captivity in situ proved abortive, and though 182 chicks have resulted from the Bombay Natural History Society’s all-India secular progamme, it may be a while before it can rank among Europe’s success with the Eurasian Griffon Vulture or the saving of the Californian Condor. Getting the vulture back into Doongerwadis may be a romantic ideal for a species as threatened, but we may have to accept that it is impractical, even inadvisable, in today’s urban crunch.

The Towers of Silence in Mumbai (and places such as Hyderabad) have found an alternative in powerful solar concentrators which desiccate the corpse admittedly not in the half-hour that a hungry flock of vultures accomplished, but which still keep to Zarathushtra’s injunction not to defile the elements. The solar-concentrator option has mercifully retained the religious relevance of the real estate goldmine of Doongerwadi. No Parsi would want the mystic eye of the vulture to be replaced by the rapacious one of the land shark.

Traditionalism is an aging community’s security blanket, most of all in matters of the imminent after-life. The dakhma is presented as the only intermediary for the true Zoroastrian. The strict rituals and prayers recited in the Doongerwadi ‘bunglis’ where the family remains closeted for three days, guarantee the untroubled passage of the soul across the mythical ‘chinvat bridge’ – and help the living towards a ‘closure’.

Unfortunately, this has turned into an instrument of emotional blackmail. The Bombay Parsee Punchayat (which administers Doongerwadi along with the community’s fabled trust funds) refuses to allow modern compulsions to compromise tradition. Those not convinced of the solar concentrators’ efficacy who want to opt for the electric crematorium have been stubbornly denied the final comfort of their 3,000-year-old rituals on the ethereal crest of Malabar Hill. Perfunctory prayers at Mumbai’s soulless municipal crematoria are just not the same.

Thinking Parsis despair over this avoidable controversy cleaving apart a community already grappling with survival, identity and rudderless youth. Their plea is that there is space enough and more in these 54 idyllic acres to enable different paths to a Zoroastrian Paradise. An exclusive crematorium for as tiny a minority is impractical anywhere, and unthinkable on swanky Malabar Hill. The Parsis who prefer cremation over the solar concentrators want only to be allowed last rites and prayers in this three-centuries’ sanctified place of solace, even if in a segregated ‘bungli’. Is it really sacrilegious, they ask, especially now that the disappeared vultures have tolled the knell of the ancient, ordained system?

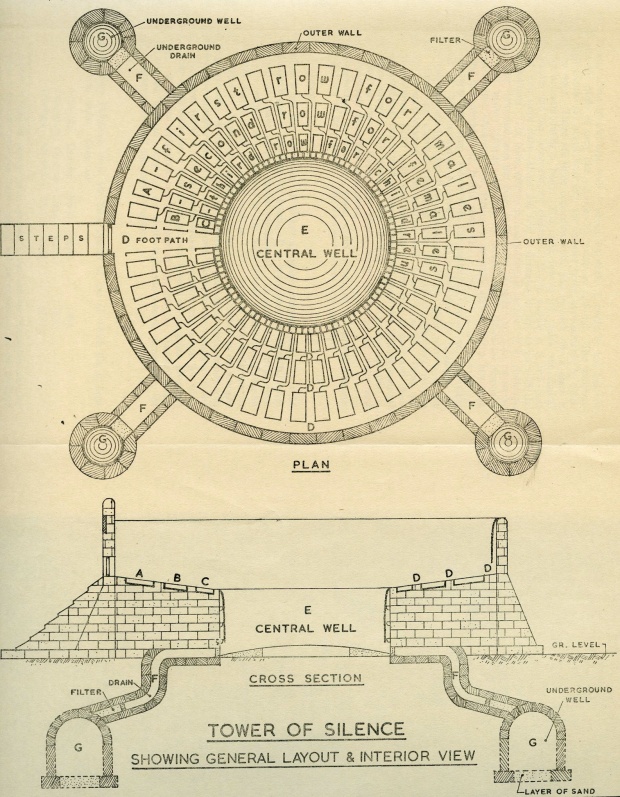

How the ‘Towers of Silence’ work

The circumference of the dakhma, a roofless structure, with only one iron door with a padlock and about 18-feet high wall, is about 300 feet. It could be less, but not much, for birds of prey like vultures to swoop in and out.

The structure has a high plinth, say about 8-10 feet, the interior being approachable by steps reserved for accommodating a body. The outer row is for males, the central one for females and the innermost for children. In the middle is a well – just a pit paved with some stone slabs – about 150 feet in diameter or less to go with the size of the dakhma.

The body, after it is laid to rest, is stripped of its clothing which is later destroyed, and the body is disposed of within a hour by the scores of birds, mainly vultures, and only the bones remain. These are removed into the well called bhandar. The bones are generally allowed for a few days to dry under the scorching sun before removal.

The question may arise. Where does the putrefying matter go and what happens to it? Four structures jut out from the inner portion of the dakhma. These are channels connected with the well or bhandar. At the furthest end of each channel is yet another well making four in all. These are outside the dakhma. Each outer well contains a thick bed of sand and charcoal. And putrefying matter washed out due to rains will meet this filtering material and stay there allowing only water to pass through. The bones, being subject to air, water and heat, get completely dried and disintegrate.

This feature originally appeared in The Guardian.