One street size does not fit all neighborhoods, because carrying traffic is not the sole function of a roadway. These are the principles enshrined in a new plan for Southwest Portland’s streets, which seeks to improve roads while bettering stormwater management and without altering neighborhood character.

The Tryon-Stephens Headwater Neighborhood Street Plan, adopted unanimously by city council in November, is the latest of three by Portland’s Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) aimed at bringing options to neighborhoods with significant challenges to walkability and bikeability. All three have targeted formerly unincorporated areas that were folded into the city in the 1980s, infrastructure gaps and all. The Tryon-Stephens area in Southwest Portland is unique — it suffers not only from a lack of safe active transportation routes, but also faces challenges due to its hilly terrain, open channel streams and poorly infiltrating soil.

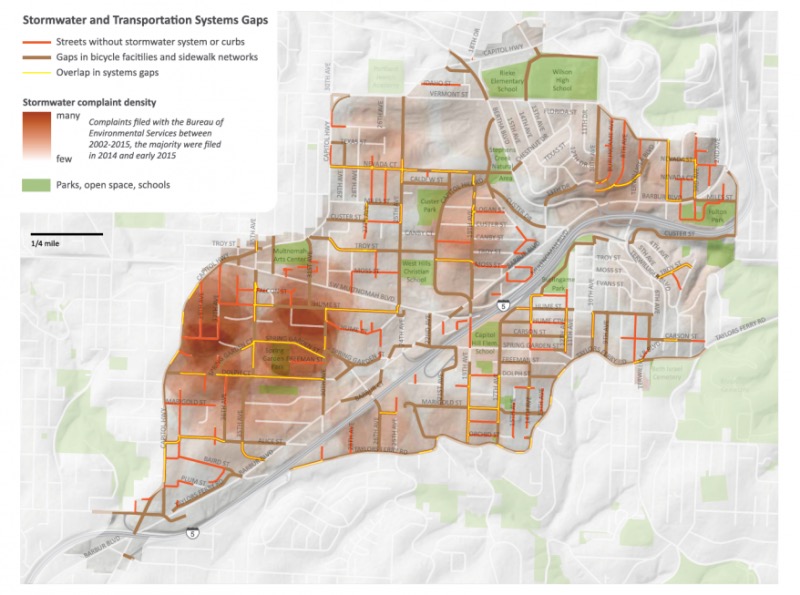

“The stormwater system is not really complete in the same way that the sidewalks and the road system is not fully developed,” says Naomi Tsurumi, environmental specialist at the Bureau of Environmental Services (BES), which manages the city’s wastewater and stormwater.

While PBOT was developing its streets plan, BES was creating a watershed management plan for Stephens Creek, one of the few urban waterways in Portland that is open and unpiped for most of its length. Pollutants and sediment — including gravel from the neighborhood’s unpaved streets — were washing into the river.

Recognizing that their priorities overlapped, the two agencies began to develop the streets plan together, the first time they have collaborated on a project of this scale. They overlaid maps of the gaps in their networks, to see where solving one lack could help address the other.

From our partners:

“This is something that is quite new actually to the city of Portland,” says Denver Igarta, senior transportation planner at PBOT. “We identify in policy now that traffic isn’t the sole function of a street. There are stormwater functions, there are also placemaking functions. If we can right-size the street improvement then we have space in the right-of-way to do other important, valuable things to build community and also to make the neighborhoods better places for the people who live there.”

More than half the streets addressed by the plan are local and residential. Improvements mostly consist of paving rutted, compacted gravel streets and making streets safer for cyclists and pedestrians.

“With all of our street plans we asked essentially three questions,” says Igarta. “What is it that you would like to see improved on your street? What is it you would like to see preserved on your street? And are there connections that are missing?”

One of the earlier neighborhood connectivity plans, for the northern neighborhood of Cully, revealed that residents did want to see enhancements, but they were concerned about roads that didn’t fit the neighborhood scale. Portland’s regulations at the time required a “one-size-fits-all” approach to street design: 28 or 30 feet of paved road, and a full buildout of sidewalks, curbs, planting strips and on-street parking.

These improvements, while they added pedestrian infrastructure and solved the headache of gravel roadways, often represented huge changes in the neighborhoods where they were implemented. Traffic speeds could increase, and sometimes street trees had to be removed. They created more impervious surface than was necessary.

From the Cully plan flowed a revise of Portland’s residential street standards, and guidelines introduced in 2012 allow PBOT greater flexibility in road designs, including options to build parking and sidewalks on just one side and to complement paving with traffic-calming measures.

“We are paving the street but without the effect of increasing the speed and volume of traffic that would normally come with the paving,” says Igarta.

“We’re trying to build a street that has a smaller footprint, less impervious surface, but also is identified as being a pedestrian-priority street.”

The Tryon-Stephens Plan goes further by creating a street typology, which identifies how much design flexibility a road can afford based on its traffic volume, terrain, natural features, land use, what destinations it serves and whether it is a key artery in cycling and pedestrian networks.

These designs allow the agency to cut down on run-off where possible, and also save money. A “shared curbless” street, a low-traffic residential street with no sidewalks and shared by pedestrians, bicycles and cars, costs about a third as much as a traditional street. The plan also recommends the city consider whether some currently unimproved rights of way are appropriate for cars at all, and close them to traffic to create more pedestrian pathways when possible.

“We intend for this plan to be useful not just for city staff to initiate projects but also neighbors who live on the street, property owners or maybe developers,” says Tsurumi. Most of PBOT’s resources serve the city’s larger arterial streets, but neighbors can band together to advocate for and collectively fund residential street enhancements. The agencies hope seeing a greater variety of street designs presented in an accessible way will encourage more residents to do so.

Southwest 19th Avenue will be the first to see improvements. The street is unpaved, missing stormwater conveyance and lacks sidewalks, but it’s also a designated urban trail, and is supposed to be a part of the city’s Safe Routes to School network. PBOT is closing it off to through traffic at both ends, one of which will terminate in a new regional stormwater facility, and implementing a “shared street” design with a 15 mph speed limit.

This feature originally appeared in NextCity.