Are great places created, or do they just happen? This question is receiving a great deal of attention right now, in academic journals and the professional press. The world’s cities face huge challenges over the next 30 years. They will have to accommodate another 2 billion people and provide a good living and meaningful economic and cultural opportunities. How can they be made better places to live? How can we maximize the chances that our public and private investment in the built environment will be successful? Great places attract talented people and businesses and generate cash flows that are sustainable and capable of growth.

Are great places created, or do they just happen?

There will probably always be something about “place” that is not capable of being defined or created—its genius loci, or essential character. However, in a number of cities around the world, we can find examples of successful long-term placemaking that have paid off from a social and business perspective. The example of Grosvenor—a major British landowner, with roots going back at least 300 years—gives us a Central London perspective.

These days, Grosvenor is a large and diverse multinational property group, undertaking investment, development and fund management from 18 offices around the world. The company’s key asset is known as “the London Estate,” comprising 100 acres in Mayfair and 200 acres known as Belgravia.

From our partners:

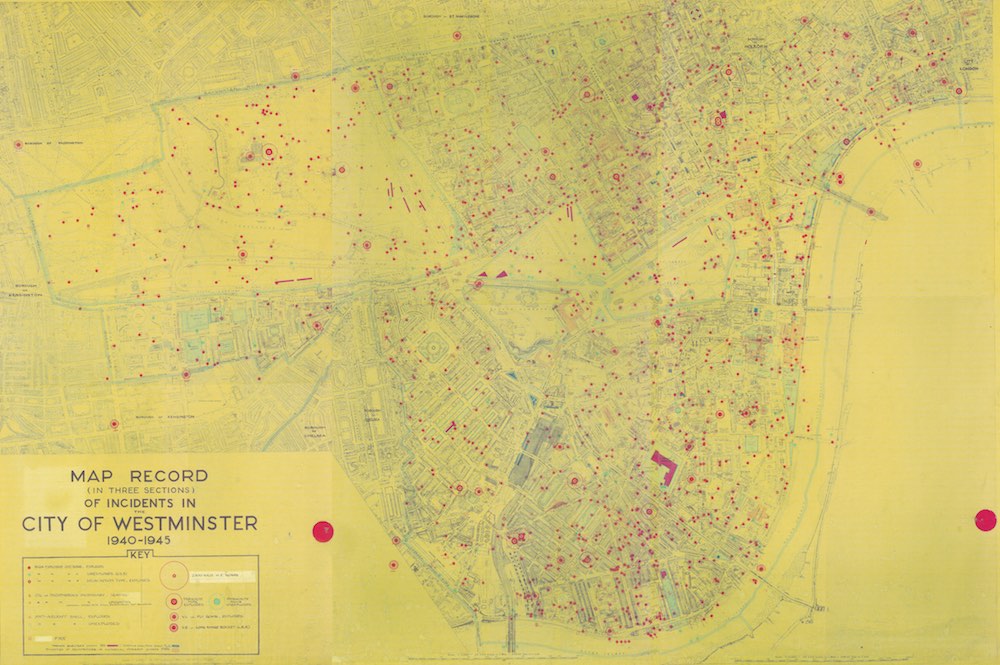

The London Estate is a very remarkable piece of land: Since it was developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, it has survived 44 separate recessions, numerous political changes and sustained bombardment from the air in World War II, which destroyed 25 percent of its building stock. Yet, in the early stages of the 21st century, this piece of real estate remains just as competitive as it ever was. Moreover, it is renowned the world over as a great place to work, live and visit. Mayfair and Belgravia contain some of the world’s most “prime” real estate. The income it generates and the values it commands in the marketplace are due to its ability to attract commercial and residential occupiers even in times of recession. What has made it so successful?

All great places need a degree of prosperity. Mayfair and Belgravia benefitted in the 19th and 20th centuries from London’s status as a capital city, major port and manufacturing center. More recently, London’s emergence as one of three major global financial centers, alongside New York and Tokyo, has generated huge numbers of very high-paying jobs and value-adding businesses, which have created demand for real estate.

As a result of success and good governance, London has a great legacy of parks, a well-functioning sewerage system, a metro, national road and rail links, and a world-class, though increasingly crowded, airport infrastructure—all of which make it a very liveable city. There is no doubt that a context of volatile but generally rising prosperity is a good background for the emergence of great places. But not all successful cities are good places to live. At a local level, economic growth still has to be converted into liveable places. Thoughtful real estate ownership and development turns economic prosperity into great places, which in turn generates further economic prosperity.

Grosvenor has made nine key contributions to creating a world-class place in London—some going right back to the initial development of the then greenfield sites.

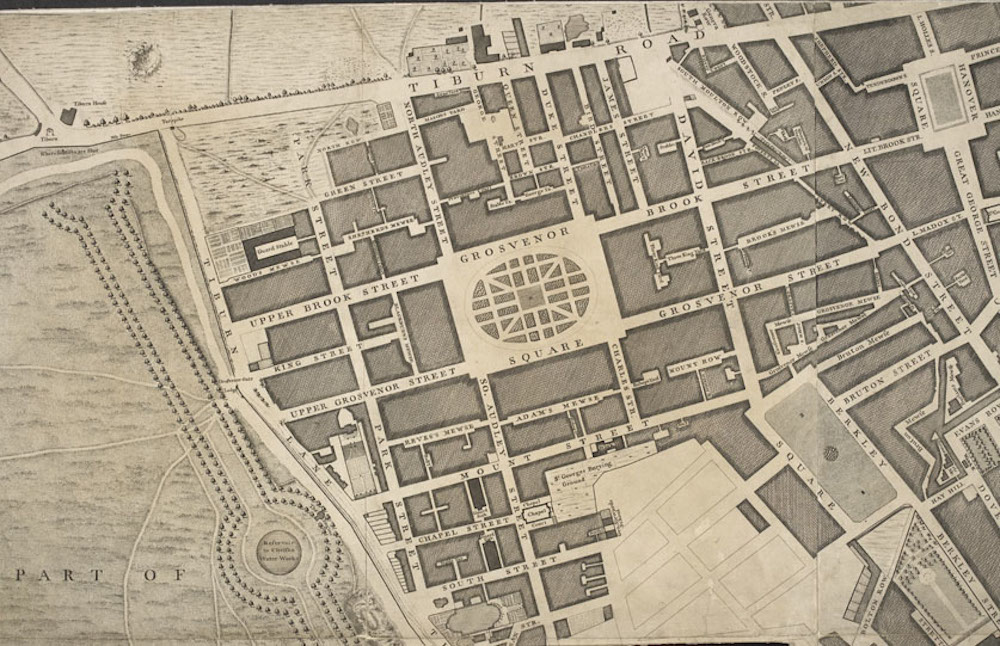

RATIONAL LAYOUT OF THE MAIN STREETS

The story of Grosvenor’s placemaking begins with the initial layout. In contrast to the rest of London and most European cities of the time, where the transport system is radial, Mayfair is laid out in a gridiron system. The main roads are wide, to accommodate carriages. This width, a benefit probably not foreseen by the original planners, has been able to accommodate changing modes of transport over time. The smaller roads, intended as service routes rather than main thoroughfares, have ended up as islands of peace and relative tranquillity, amongst the general hubbub of London. The major benefit of the gridiron system is that the traffic does not converge on one very small central location, so congestion and delay are reduced. Moreover, the estate is highly permeable: Traffic can pass from north to south and east to west, via a number of points of ingress and egress. The main traffic routes have numerous crossing points, created in the years since the initial development, so even in the era of the car, pedestrians can move around with ease, by any route they choose.

PLENTY OF GREEN SPACE

At the center of Mayfair is Grosvenor Square, bigger than Trafalgar Square and the second-largest square in London. It is now, and has always been, a well-tended and rather beautiful area of green space. Here the original designers also had foresight. An essential element of high-density urban living is publicly accessible parkland. It is not just the space for exercise that is important; there is something deep within the human psyche that finds green space both attractive and relaxing. Parks have been a central component of the hugely successful residential development of Battery Park City in New York. In Tokyo, one of my favorite cities and one of the world’s great places, even locals admit that the endless concrete gets them down from time to time and they have to get out of the city. In the 300 acres of Mayfair and Belgravia, a full 25 acres are given over to urban parks.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING AND BALANCED SOCIAL MIX

Mayfair and Belgravia are world famous for their high-end residential properties. What is less well known is that approximately 30 percent of the housing units are affordable, or rented out at below-market rents. Moreover, the provision of affordable housing goes back to the mid 19th century. In part, this reflects the natural need of a wealthy residential area for workers. However, it also reflects a concern for the living conditions of ordinary workers. The Page Street flats, on Grosvenor’s Millbank estate, were built by the Grosvenor Estate to rehouse workers whose housing had been destroyed when the Thames burst its banks in 1929 (a reminder of what life was like in London before the Thames Barrier was built). The flats were designed by one of Britain’s foremost architects, Edwin Lutyens. Be this as it may, the point is that great places are inclusive, and in successful, market-driven cities, around 25 percent of the housing stock will need to be provided at below-market rents.

INTELLIGENT EVOLUTION OF ARCHITECTURAL STYLE

There are only 18 original 18th century buildings left in Mayfair; yet, if by magic, someone was brought back from that time and taken for a walk around Mayfair, I am convinced they would recognize it quite easily. This is because new buildings, often not developed by the landowner but by someone with a long lease on the land, have had to be approved by the estate as being “in keeping.” The architecture has had to reference the past, and the other buildings nearby, but density and massing have not been overly restrictive. This intelligent evolution of style preserves the sense of place, but gently increases floor space. The two images of the northern terrace of Grosvenor Square show how post-World War II building harks back to the original facade. The modern building is not particularly elegant, but it fits in and draws some charm, which it needs, from the surrounding area.

CONSISTENCY OF ARCHITECTURAL STYLE

Belgravia is known for its consistency of style, with its creamy stucco facades and black railings. In fact, the painted facades only came in after the clean air acts of the 1950s. Before that, the buildings would have been a yellowy, lime-washed stucco. The stucco would be rather grimy, a legacy of the smoke from hundreds of domestic coal fires. Today, each property has to be painted by the leaseholder once every three years with good quality oil-based paint, to a tint approved by the estate surveyor. The railings always have to be black. Some have attempted to paint their finials gold, but this has been resisted. The result is visual harmony and a strong sense of place.

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE RETAIL STOCK

The opportunity to revitalize Belgravia with a coat of paint is an example of active management. In creating and maintaining great places, there is a need to go beyond this to curatorship. In 2000, retail rents in Mount Street, with its rich terra-cotta facades that date back to the 19th century, were £90 per square foot. The street was dominated by antique dealers who were slowly moving their businesses online. Now rents are around £500 per square foot. The transformation was triggered by the arrival of Marc Jacobs. Grosvenor’s retail managers were aware of the surge in demand for luxury fashion items and decided to relocate, by consent, the antique dealers to other parts of the estate. The street was turned into a cluster of super-luxury fashion brands. Care was taken to maintain the convenience retailers that inhabited the area, which are essential for the residential occupiers and local office workers. Now the street hosts brands such as Oscar de la Renta, Christian Louboutin, Goyard and Céline and is an internationally acclaimed high fashion location. Great places need to be economically vibrant and sometimes that means proactively changing the tenant mix.

FLEXIBILITY WITHIN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Urban economies change over time. Mayfair, when it was laid out in the 19th century, was largely residential in use. After World War II, it emerged as a leading office center, housing the headquarters of numerous companies. A Mayfair address became an essential part of a company’s credibility, particularly if it wanted to tap the public markets for funding. The Georgian and neo-Georgian buildings stayed the same, preserving sense of place, but, crucially, the occupier base changed and the economic vitality was preserved. Over time, banking and wealth management businesses joined the corporate headquarters, and in the 2000s Mayfair saw the emergence of a hedge fund cluster. More recently, because of huge global interest in living in London, properties are being converted back to their original residential function. Flexibility within the fabric of the built environment is the key to reconciling economic change, which is inexorable, with maintaining the vitality of place. Without this flexibility, places can be destroyed by economic change. Grosvenor’s genius is to sensitively go with the economic flow, adapting to the emergence of new occupiers.

INVESTMENT IN THE PUBLIC REALM

Due to the initial layout, Mayfair and Belgravia have many high-quality public spaces. In 2007, recognizing the increasing importance of public space in live-work environments, Grosvenor developed, in conjunction with the Danish architect Jan Gehl, a strategy for the public realm. This includes enhancements to pedestrian areas and investment in international-quality public art. The public realm, or the space between buildings, as Gehl puts it, is actually the most important component of place. A good public realm makes people want to dwell there, and creates life and vitality and transactions. By contrast, a poor public realm makes people hurry home. In fact, many cities around the world are rediscovering the importance of the public realm, particularly in attracting talented, “work anywhere” individuals.

COMMUNITY BUILDING INITIATIVES

Another recent management initiative, based on the idea of creating communities, are arts festivals held in numerous garden squares across the estate. Of course, good places will create their own social life, but there is a role for events that are out of the ordinary, because they create interaction between people, which is both the consequence and origin of place.

We started with the question: Can developers or landowners create great places? The answer has to be a resounding yes. Grosvenor is a great example, but it is not the only one. The interesting thing about Grosvenor is that it is a private-sector developer, investor and landlord. It has used, over the long term, its large consolidated land holding to create great places that are remunerative but also provide beneficial social outcomes. It is not obvious that democratized land use, exercised through city authority planning departments, has done better.

This feature originally appeared in CBRE Blueprint.