Rural development programmes to wean poppy farmers off their illicit crop contend with lack of roads, water and power in remote areas plagued by militias.

UBo sits on the floor of his bamboo hut and puts away a plastic tray covered with a small heap of what looks like sticky, brown tar. This is the day’s opium harvest, which he and his family scraped off the bulbs of their two-acre field of poppies.

His farm, at the foot of a lush mountain, in eastern Myanmar’s Shan state, includes another two acres of rice. Opium will provide his family of seven in Pe Kin village with much-needed cash – his 6kg of opium could fetch about $1,800 (£1,250) – while the paddy provides food.

“We grow poppies because other [cash] crops don’t grow well here. Corn is not good with the poor soil and weather,” says U Bo, 57, a farmer from the Kayan ethnic group.

From our partners:

“I spend most of the money [from opium] on sending my children to school, the rest I use to plant fruit trees,” he says. The opium is sold through a network of secret traders.

His family is one of the estimated 133,000 households (pdf) in Myanmar, mainly found in impoverished, remote regions, who last year grew poppies across 55,500 hectares (about 137,000 acres) of land, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Myanmar is the second largest producer of opium after Afghanistan.

The trade in opium and its derivative heroin is controlled by many rebel groups (pdf) and pro-government militias who use it to fund a long-running civil war. The opiates, along with huge amounts of methamphetamine (pdf), end up in China and across south-east Asia.

While the hardy plant has long been a lifeline for poor farmers, U Bo says he is tired of growing a crop that is taxed by armed groups and corrupt police. “I really hope the new government can bring good changes. We would like to have power, roads, water — then I don’t have to grow poppy,” he says.

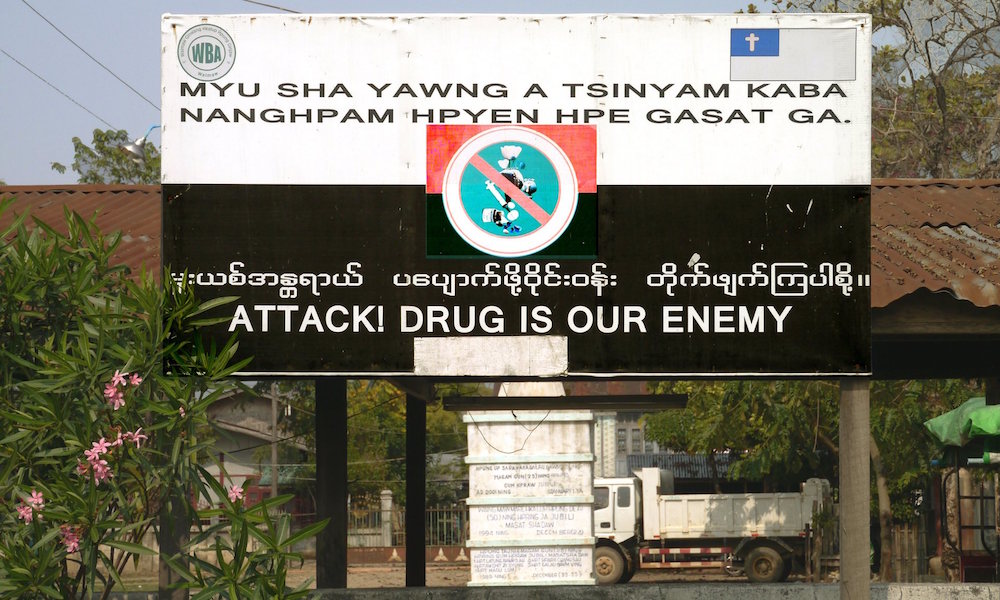

The ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) faces the task of boosting rural development to improve livelihoods and reduce opium cultivation. It will also have to tackle widespread drug abuse in some regions.

The Drug Policy Advocacy Group, comprising local NGOs, healthcare workers and independent experts, is hoping the new government will reform what they regard as harsh, ineffective drug laws and policies.

“We want them to revise the 1993 drug law to decriminalise drug use and reduce sentences for poppy farmers, and we want more health services for users,” says Nang Pann Ei Kham, the group’s coordinator. “We have contact with advisers to the new government leaders; hopefully we can draw their attention.”

Founded in 2014, the group has been organising events with police, NGOs, international aid groups and organisations representing farmers and drug users to discuss policy changes.

The first public event was held in Yangon in April. A member of the Myanmar Opium Farmers’ Forum told attendees that the government should allow subsistence poppy farming until it can provide alternative cash crops and improve land rights, infrastructure and basic services. “Many laws were adopted by the government without consulting opium farmers – we should now raise our voice,” said Lashila, a community leader from the Shan ethnic group.

Khin Maung Myint, an NLD MP from Kachin state, said his party had yet to decide on drug law reforms, but would prioritise rural development over poppy eradication and “help farmers change their livelihoods”.

The UNODC is already attempting to do this. It has set up a co-operative among 800 farmers in Shan state to grow 550 hectares of coffee for sale on domestic and export markets. It worked with the state land records department to give farmers land rights certificates. The programme is expected to expand to 1,300 hectares, and reforest areas cleared for poppies.

“Reducing illicit cultivation can only be achieved when the socio-economic conditions and livelihoods of rural households have been improved,” says Troels Vester, UNODC’s Myanmar country manager.

Such initiatives, however, run up against the realities on the ground. In Shan and bordering Kachin, the army allows militias to control vast poppy areas if they help fight rebel groups.

Tom Kramer, a Dutch researcher with the Transnational Institute, says the army’s position on illicit activities by its militias is an “obstacle for reform” of drug policy and unlikely to change until there is a nationwide peace accord.

In Kachin, local leaders complain that the influx of cheap drugs is destroying their communities. A local NGO estimates a third of all male university students inject heroin, though there is scant official data.

A lack of government action in the region has led to the emergence of vigilante groups, such as Pat Jasan, established by leaders at Kachin Baptist church.

Since 2014, Pat Jasan has mobilised thousands of volunteers to clear poppy areas and apprehend hundreds of drug dealers and users. The latter are taken into controversial, Bible teaching-based rehabilitation.

Kramer says the vigilantes’ emergence indicates the public’s desperation over the drug trade, but to address the problem, he says, “you need a development-led approach, an inclusive peace process, and [to] tackle corruption”.

U Bo says he is unaware of the abuse and conflict linked to the drug trade. “I don’t know about these things, I only grow poppies,” he says. “But I just want to grow a different crop and would like the government to support us.”

This feature originally appeared in The Guardian.