Anyone can use the city’s new guide to affordable housing–and eventually, it could go global.

Who gets to decide what “good” design is?

In the past, it might have been the critic who wrote about a building, or perhaps the architect who designed it, or the city agency that approved it. But a quietly ambitious project from New York City’s Public Design Commission is working to give everyone–from citizens to politicians–the language to talk about and advocate for good design.

From our partners:

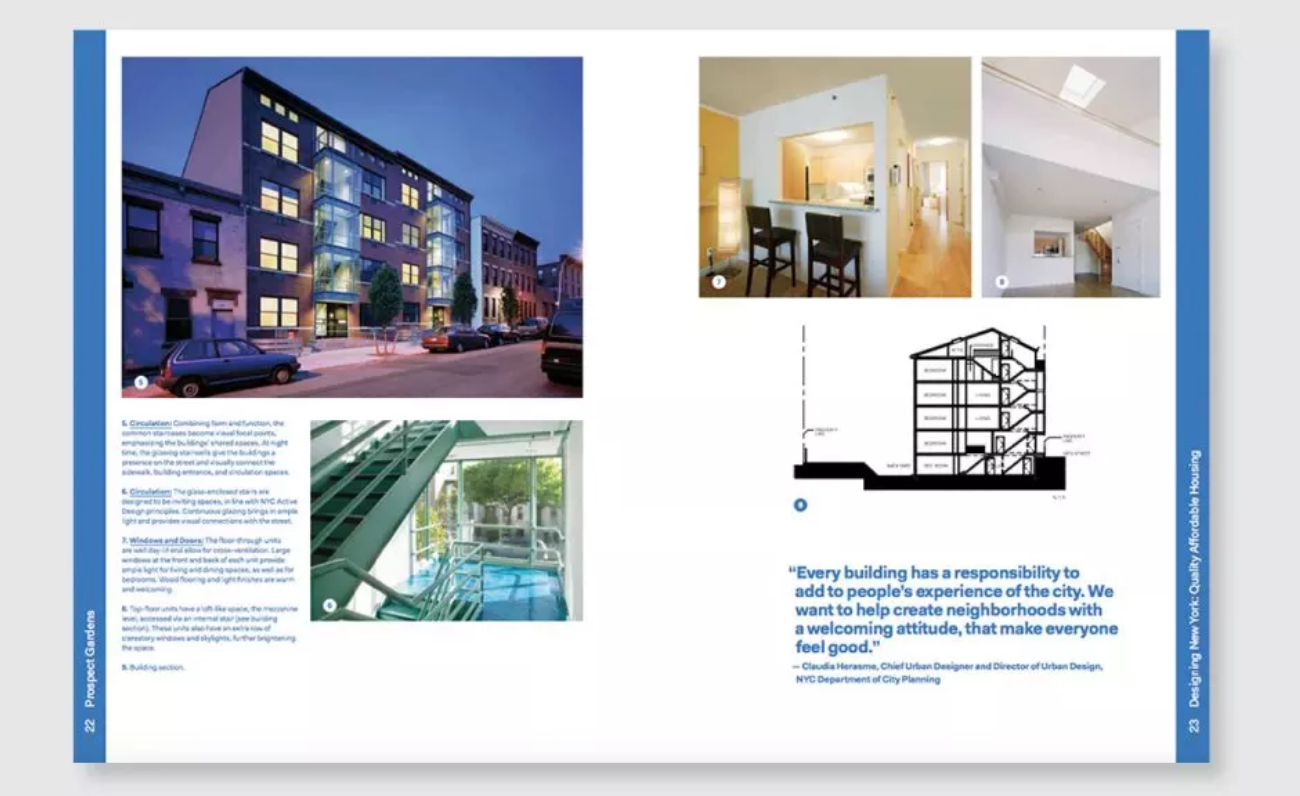

“It happens everywhere: A developer will say, ‘In order to get the affordability you want, or in order for this to happen in X amount of time, we have to do it this way,’” Moore says. “And these are projects that have proven that is not true.” A moment later, he adds, “in New York City, which is one of the most difficult development environments you’ll find anywhere.”

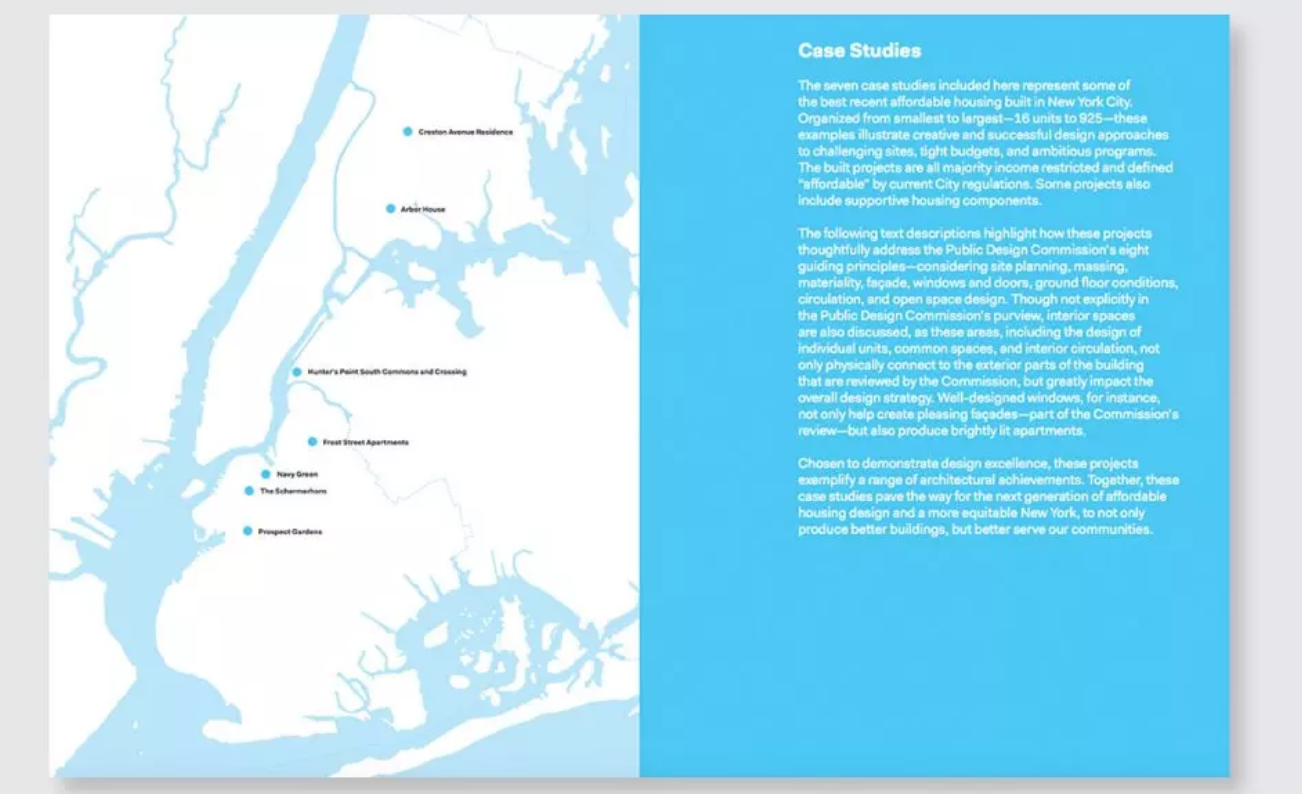

The buildings in the report are diverse, and the scope of the guide is broad. It details a housing development in the Bronx where access to affordable and healthy food is hard to come by–so the architects integrated a hydroponic farm on the building’s roof, offering fresh food to occupants through a CSA agreement. Another project on a former brownfield site in Brooklyn, once home to a naval prison, was transformed into “mini-neighborhood” with affordable housing organized around a wide common green.

The guide, which is free online and will be distributed to stakeholders in the city, represents just the beginning of the project’s ambitions. The Public Design Commission has received funding to turn the project into an online platform–perhaps even an app–that anyone in the world can access and add to. They’ll spend the next six months developing an initial online version, and eventually, it could function as a platform for sharing successful design solutions all over the world.

“There’s a really broad spectrum of people that could use a resource like this,” Moore adds. “So that’s really the ambition . . . to not only talk to architects, or people in government, but to [create] a reference point for all the people who need to become more literate and aware of all the different ways that you can accomplish good design in housing and community development.”

This feature is written by Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan & originally appeared in FastCo Design.