For a few brief generations, at least.

ONE MILLION: THAT’S ROUGHLY THE number of oysters New Yorkers ate, every day, in the mollusks’ 19th-century heyday. That’s a rather mind-boggling amount of bivalves, but the numbers add up once you delve into New York’s long and fruitful history with this particular shellfish.

Archaeologists have discovered New York harbor-area middens—ancient shell piles—dating back to 6950 B.C. Oysters thrived for millennia in the brackish waters around New York Harbor, keeping the estuary clean thanks to their natural filtration abilities, and serving as a favored food for the Lenape people who once lived there. When Henry Hudson arrived in 1609, there were some 350 square miles of oyster reefs in the waters around what is today the New York metro area, containing nearly half of the world’s oyster population. European settlers wasted no time in turning this natural resource into a powerful industry.

By the 18th century, immigrants to what was then known as New Amsterdam referred to Ellis and Liberty islands as “Little Oyster Island” and “Great Oyster Island,” respectively. The Dutch named the waterfront Pearl Street for a midden, later paving it with discarded oyster shells (though they were disappointed to discover that New York oysters don’t actually produce pearls). New Yorkers started eating oysters en masse and shipping the delicacy to cities across the U.S. As the culinary historian Mark Kurlansky writes in his 2006 book The Big Oyster, “The combination of having reputably the best oysters in the world in what had become inarguably the greatest port in the world made New York City, for an entire century, the world’s oyster capital.”

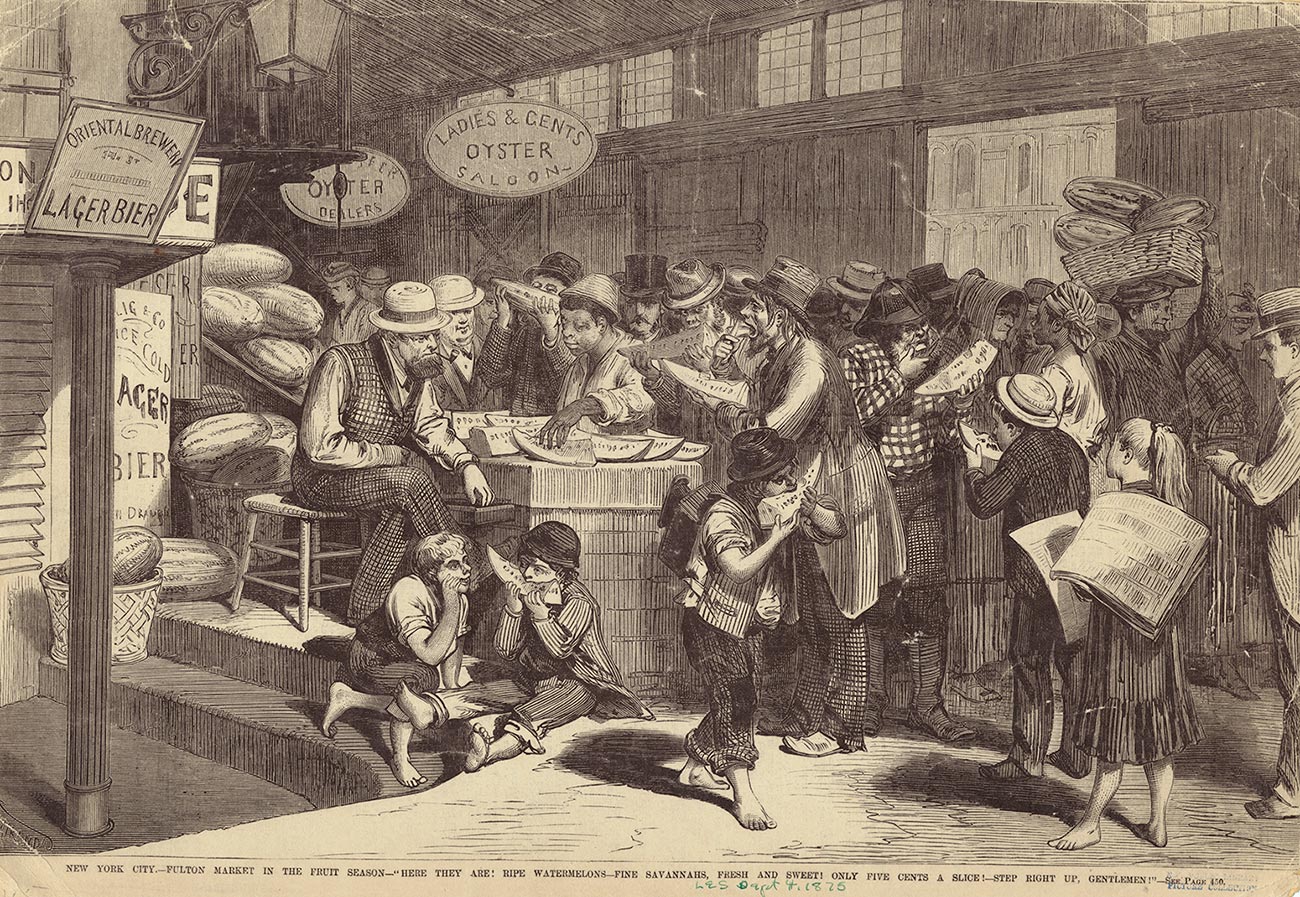

Oysters were everywhere in 19th-century New York. Oyster cellars advertised oysters “in every style,” (raw, fried, packed into pies and stews) and ranged from higher-end establishments to workaday pit stops offering all-you-can eat bivalves for six cents a pop. Cellar proprietors advertised their businesses by tying red muslin balloons over wire and illuminating them with candlelight, with one cellar reportedly even doubling as a post office for the Bowery village.

From our partners:

If the cellars weren’t to your liking, you could skip them entirely and just buy oysters off carts on the street, along with hot corn and peanuts. Oysters were so ubiquitous that Annie Hauck-Lawson and Jonathan Deutsch, in their book Gastropolis: Food and New York City, claim that even “the very poorest New Yorkers had no other substance than oysters and bread.” As for the millions of shells New Yorkers produced during these years of heavy oyster consumption? They were used to pave roads, crushed into mortar paste to fuel the building boom (Trinity Church, for example, was built with oyster shell-mortar paste), or burned for lime (a practice which was eventually outlawed due to its unfortunate, acrid smell).

New Yorkers needed something to wash down all of those oysters, too. Enter beer, which has an equally rich history in the city. The oldest-known brewery in the U.S. opened in New Amsterdam in 1633. But the beer scene really took off a few centuries later, in the mid-19th century, with the arrival of German immigrants who introduced a new style of beer called lager, which soon accounted for four-fifths of local beer production.

It didn’t take long for New Yorkers to start combining their love of oysters with their love of beer; the mollusk became a common snack at taverns and saloons across town. There are records of one 1850s-era oyster barge that served as a speakeasy for oystermen, who offloaded their wares at the rear of the barge, where they were quickly processed and sold fresh to wholesale customers lining the piers. Local legend has it that the second floor was home to a bathtub and a brothel for oystermen. That barge was later turned into a restaurant called, creatively, the Old Barge (advertising “choice beer, wines and liquors, hot meals”), and eventually a rowdy dive bar before being bought and refurbished by two Brooklyn restaurateurs in 2015.

Unfortunately, for as much as New Yorkers loved eating and selling oysters, they didn’t go about it so sustainably. A combination of overharvesting, the expansion of the city’s shoreline with industrial materials, and a serious lack of waste management contributed to the depletion of the region’s once-abundant oyster beds. By 1927, the last of the New York City oyster beds were officially closed for business. New York City’s oysters had become too contaminated to eat.

The passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 helped somewhat, but New York still has a ways to go before urban oysters are safe to eat again. In 2014, a citizen science project called Billion Oyster Project launched with a long-term goal of adding one billion live oysters back to New York Harbor to repair its ecosystem by 2035. Given that a single oyster can filter 30 to 50 gallons of water a day, and the city’s waterways are far from pristine, this is a worthwhile goal.

Slightly farther afield, in Long Island Sound, edible oysters flourish, particularly briny varieties such as Bluepoints (which abound in the waters surrounding Blue Point, a small town on Long Island’s South Shore) and Peconic Golds. The oyster oasis in this part of the state is also close to Blue Point Brewing Company in Patchogue, named for the oyster variety and the island upon which they were first discovered.

For lovers of oyster and beer, Patchogue makes for a perfect jaunt, just a short (less than two hours) Long Island Rail Road trip away. New Yorkers indulging in a summer Friday can even get a head start at Penn Station: you can bring a Blue Point beer aboard the LIRR (pro-tip: Rose’s Pizza on the Long Island Rail Road level offers Blue Point beers in cups of sizes up to 32 ounces). And starting this Labor Day, be on the lookout for Blue Point’s Good Reef beer to help support the Billion Oyster Project.

Recent efforts demonstrate that there’s still hope that New York City can reclaim its well-earned reputation as the oyster capital of the world. Until then, city dwellers hungry for fresh oysters and cold beer can visit Patchogue.

This feature originally appeared in Atlas Obscura.