Wealth is inherently collective. Whether it’s land or property, shares of a company, artwork or just cash, its market value is based on how many others want it and have the means to obtain it. Perception matters. The fewer people who want what you’ve got, the lower its value.

Because so much of household wealth in the United States is tied up in the housing market, the stories we tell (or don’t tell) that shape our perceptions of where we want to live and among whom we want to live, end up having a dramatic and ongoing effect on race-based wealth inequality. This, according to the authors of a new study, released this week, from the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

“Much of the research on implicit bias focuses on individuals’ perception of individual members of an oppressed class. However, we should expect some of these biases to carry over into places where there are high concentrations of black people,” write authors Andre Perry, Jonathan Rothwell, and David Harshbarger. “The value of assets — buildings, schools, leadership, and land itself — are inextricably linked to the perceptions of black people.”

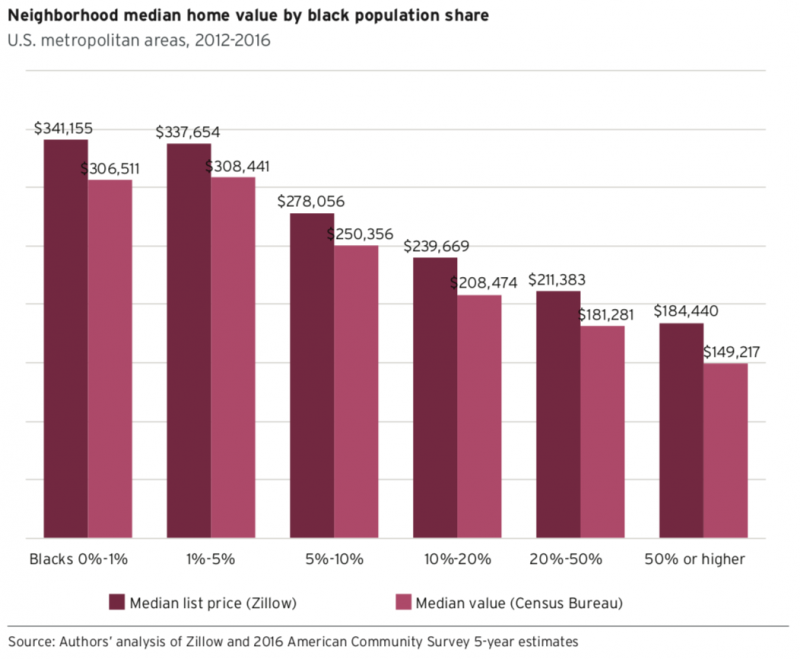

If black people are therefore the only people who want to live around a lot of other black people, that would be a major reason why the higher the concentration of black people in a neighborhood, the lower the home values in that neighborhood. As the authors found, in the average U.S. metropolitan area, homes in neighborhoods where the population is at least 50 percent black are valued at roughly half the price as homes in neighborhoods with no black residents.

From our partners:

To illustrate the point about existing perceptions of neighborhoods with large concentrations of black people, the authors cite a recent incident in which the namesake of the University of Mississippi’s journalism school posted a Facebook status decrying the growing prevalence of black residents in the neighborhoods around the university.

“To be clear, the sheer presence of black women doesn’t devalue homes,” the study authors write. “However, signaling they do can negatively impact housing markets.”

According to the authors’ analysis, differences in home and neighborhood quality do not fully explain the lower value of homes in black neighborhoods. Homes in majority-black neighborhoods are worth $48,000 less than homes of similar quality in neighborhoods with similar amenities but few or no black residents, the authors found.

In total, the authors tabulated that majority-black neighborhoods contain 3.2 million owner-occupied homes worth an estimated $609 billion — but those homes would collectively be worth $156 billion more if not for the lower value that comes with the perceptions associated with being in a majority-black neighborhood.

The undervaluation of majority-black neighborhoods is of particular concern for cities. The nationwide fervor for homeownership helped precipitate the subprime mortgage crisis, which disproportionately targeted neighborhoods of color and wiped out a generation or more of black wealth. Still, home equity remains a key source of capital or collateral to help start or grow a business, or to help pay for college tuition.

As noted in the study, 90 percent of the nation’s 40 million black Americans live in metropolitan areas, and majority-black neighborhoods in metropolitan areas are home to 14.4 million non-Hispanic black residents as well as 5 million residents from other racial and ethnic groups. Majority-black neighborhoods also house a large portion of the nation’s human capital, including 2.3 million adults age 25 and older, 5 percent of the nation’s metropolitan population with a bachelor’s degree, 10 percent of its public schools and also 6 percent of its libraries. Some three million businesses are also located in majority-black neighborhoods.

There are 113 metropolitan areas with at least one majority-black neighborhood across the country, and the study release includes an online database to look up the state of housing values in each metropolitan area. The metro with the largest gap was Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk in Connecticut, where homes in majority black neighborhoods are worth only 17 percent of the value of homes in neighborhoods with less than one percent black population. Charleston, S.C., and Savannah, Ga., were not far behind.

In Florida and Alabama, a handful of metros actually had majority-black neighborhood home values that met or even exceeded home values of neighborhoods with few or no black residents.

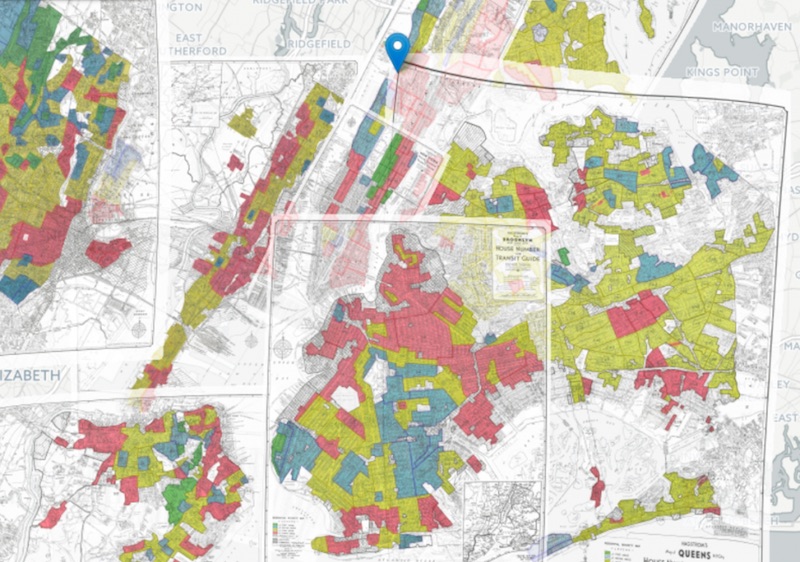

The authors say history is a factor in the undervaluation of black neighborhoods. The study references the legacy of redlining — how racial zoning and racial steering by real estate agents gradually segregated cities by race, combined with public policies enacted in the early and mid-20th centuries that subsidized or incentivized the large-scale construction and purchase of mostly single-family homes exclusively to white families while denying the same to black households and other minority groups.

Redlining shaped the hyper-segregated cities of today, with large pockets of poverty concentrated in predominantly minority neighborhoods. Without equal access to capital to develop, build and maintain their properties or buildings, majority-black and other majority-minority neighborhoods fell into disrepair, priming these majority-minority neighborhoods to be demolished to make way for highways or other large-scale public projects during the era of “urban renewal.”

Although redlining explains how many neighborhoods became majority-black in the first place, the study authors claim historic disinvestment related to redlining does not explain the entirety of the gap between home values in majority black neighborhoods and neighborhoods with few or no black residents. Ongoing perceptions about black people and black neighborhoods remain a major factor behind that gap, in their analysis.

Finally, the authors also explored the relationship between housing wealth and the economic prospects of future generations.

“If properties in black neighborhoods were priced equally as those in white neighborhoods, black children coming of age in the 1990s and 2000s would have had much more wealth to draw upon to pay for things like private schooling, tutoring, travel, and educational experiences, as well as higher education,” they write. “Greater property wealth may have also facilitated higher rates of entrepreneurship among black parents, which may have positively affected children.”

Indeed, they found, black children born to low-income families had higher incomes as adults if they grew up in a metro area that “valued black property closer to its observable market characteristics.”

“The evidence does suggest there may be underlying links between the two phenomena that warrant further exploration,” the authors write.

This feature is written by Oscar Perry Abello & originally appeared in NextCity.