If everyone who recently migrated to cities in the region were a country unto themselves, it would be the world’s sixth largest.

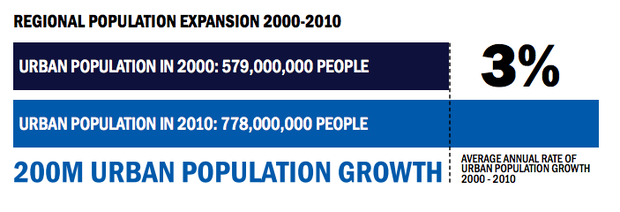

Almost 200 million people in East Asia migrated from rural areas to cities between 2001 and 2010. If all these people were to band together and declare themselves a country, it would be the world’s sixth largest. That’s a lot of people.

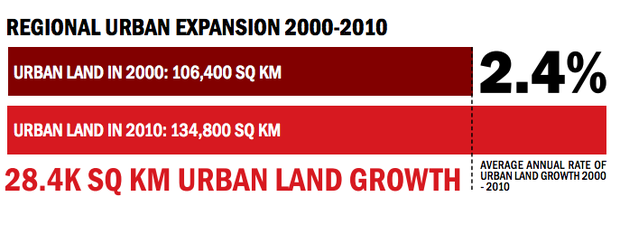

A new World Bank report uses satellite imagery and geospatial mapping to compare this influx of people with the expansion of urban areas from Mongolia and Myanmar on up to Japan. It finds that although cities in the region expanded at breakneck speeds during this period, they couldn’t keep up with ballooning urban populations. New residents poured into cities at an average of 3 percent per year, while land expansion happened at a 2.4 percent annual rate, according to the report.

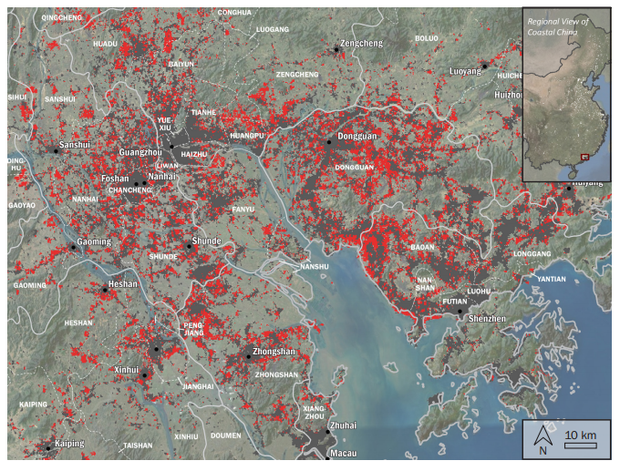

China rules the roost, accounting for 80 percent of the region’s urban land growth. But while China is dominating in absolute numbers, it’s smaller countries like Laos and Cambodia that are transforming at the fastest rates: 7.3 and 4.3 percent urban expansion per year, respectively. Because these countries have historically been rural they literally have more ground to cover,explains Judy Baker, author of the report.

From our partners:

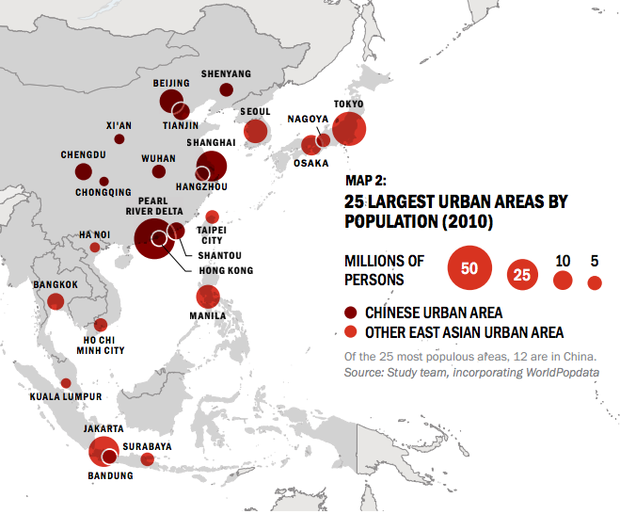

In terms of population growth, as well, China is formidable. It houses 600 out of 869 urban areas in the region that contain more than 100,000 residents.China also contains 12 of the 25 largest ‘megacities‘—those with more than 1 million people. These have doubled their area in the decade surveyed. Outside of China, urban centres in Malaysia, Cambodia, and Vietnam grew the fastest (Interesting side note: despite the hue and cry made about “megacities,” small and medium-sized urban areas increased more in space, population, and growth.)

The report also examines the link between urbanisation and a country’s GDP. High-income countries, like Japan and Korea, had the lowest growth rates because they’re already pretty urbanised. Cities in middle-of-the-rung countries, like Indonesia and China, spread out quicker. Lower-income countries, like Cambodia, showed the fastest population growth. Whatever the current GDP of the country, more urbanisation means more economic activity, which leads to a higher national income, says Baker. The chart below shows that all countries experienced a jump in GDP with urbanisation.

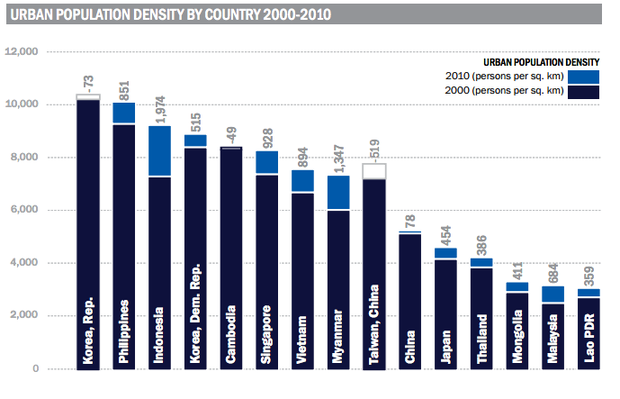

The other thing the report backs up is that, on the whole, urban density in the entire region is really high. In fact, the density of the region’s urban areas is 1.5 times the average density of cities around the world. This is a good thing, says Baker, as compact urban development, done right, can lead to walkable, livable cities with affordable transport.

Of course, the extent of urban density varies by country. Indonesia, for example, has seen the most growth in density because its growth in population surpasses its growth in urban space. On the other hand, China’s urban density remained stable because its spatial expansion rate is keeping up with the rate of urban migration.

The point of the whole study is to give planners a lay of the urban land across East Asia so that they can tackle problems like urban fragmentation in the region. Baker also hopes that people combine the released dataset with others to reveal new insights that help plan for the future. At the moment, people who live in cities only make up 36 percent of the region’s population, and only 1 percent of the total area is urbanised. This is just the beginning.

This article originally appeared in CityLab.