Raised in New York, fed by newspapers and nourished by urban life, comics tell the secrets of cities … and of those of us who live in them.

If you have made it this far into the story, the chances are the city in your mind is New York. Or at least some version of it. Surely no streets have been portrayed on the pages of comics as often as Manhattan’s, most famously as Metropolis by day and Gotham by night. Not to be outdone, Spider-Man once even said “I am New York.” Batman, the Ninja Turtles, the Fantastic Four, Superman and a host of other do-gooders in stretch pants may have thoughts on that. As might Mitchell Hundred, who, despite possessing superpowers unsuited to desk work, hangs up his cape and becomes mayor of the city in Ex Machina. “Stopping bullets ain’t in your job description anymore, boss,” says his aide when the guns come out.

There may not be a birth certificate for comics (especially if you embrace the broader definition of “sequential art“), but the strip was certainly raised in New York, and well fed by the competition between newspapers and their publishers in the early 1900s. Well nourished, too, by the meat and drink of urban life. The countryside is a fine habitat for spiders, but how is Spider-Man meant to get around with nothing but branches to swing from? Superboy grew up in farmland, sure, but the call for caped crusades came from the city – because cities have people, possibilities … and crime.

From our partners:

Of course there are exceptions. Good ol’ Charlie Brown, safe in the midwestern bliss of his strip, doesn’t have to get involved with that delinquent nonsense – but if we’re in the city, crime is on the menu. Gotham has had many makeovers in Batman’s time, but, as Batman Unmasked author Will Brooker says: “The defining characteristic of Gotham must be that there is always crime. Because Batman is, on one key level, the man who fights crime.” (Exactly where in New York, however, is hard to nail down. Over the years, Gotham has had to be to be a very adaptable place, perhaps because definitions of its locale, such as that of the journalist William Safire – “New York below 14th Street, from SoHo to Greenwich Village, the Bowery, Little Italy, Chinatown and the sinister areas around the base of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges” – passed their sell-by date as Manhattan cleaned up under mayors Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg. The recent Christopher Nolan films owe a much greater debt, in appearance, to Chicago.)

Yet while villainy may be prevalent on comic-book streets, those streets come in myriad forms. Whatever you imagine a city can be, you’ll find it out there on those waffled pages. The debated differences between Marvel’s landmark realism v DC Comics’ fantasy town-planning seem fairly niche when you visit Philippe Druillet’s Delirius, a city that covers an entire planet (not unlike the sprawling carbuncles of Judge Dredd’s precinct, Mega-City One). Delirius is a planet dedicated to enjoyment: “Four million square miles of untold pleasures for everyone … Sumptuous casinos and low dives! Wild night-clubs! Temples of debauchery! Blood-soaked arenas!” For protagonist Loan Sloane, where there’s pleasure, there is also plenty of pain.

Frank Miller’s Basin City – a place that only began representing itself honestly when it dropped those first two letters to become Sin City – is a town where even the priests say things like: “Ask yourself if that corpse of a slut is worth dying for.” It’s so hopeless and mean that the grime can’t be contained in classic urban cauldrons such as “projects” and docks: even the forests and farms surrounding it crawl with menace. Everywhere is black and white and red all over. The New York of Alan Moore’s Promethea is initially also portrayed as a kind of Babylon, but there is at least some redemption here as it is transformed, straight along biblical lines, into an ectopian paradise – “a heavenly radiant city”. The pages glow with electric blues, golden sunsets and sex.

Want to see Paris in 2023? There’s the Nikopol Trilogy. Berlin 1928-1933? Jason Lute’s Berlin (City of Stones). Hiroshima just after the bomb? Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa. How a Belgian architect imagines the future? Les Cités Obscures, from François Schuiten – beautifully constructed cityscapes that twist and knot as they reach for the sky. Cleveland? Page Harvey Pekar. The life of a man who lives on top of a building between two hoardings? See Owen D Pomery’s Between the Billboards – a contemporary “self-published comic series following the main character James Ebner and his detached existence”.

As this list makes clear, cities – as places that ferment action and opportunity – are obviously a great source of narrative for comics. But perhaps the connection is even deeper. There’s as much action to be found in the private world of urban living as there is spilling out on to the streets. As the Riddler once asked: “When is a man a city?”

Or, as Sophie Yanow puts it in War of Streets and Houses, published just this year: “Where else can a queer kid go to find people like them to experiment with the possibilities only made real by city life?” The strip’s spare panels, often just lines drawn on a white background, aren’t focused on buildings but on the mental and physical struggle cities can create. Yanow grew up in the woods, moved to Montreal and felt the kettling pressure of urban control while taking part in the 2012 student strikes. How people are moulded by cities and their authorities is also captured in Will Eisner’s Life on Dropsie Avenue and The Building, both of which unpick New York’s historical fabric; and the interests of Chris Ware’s Building Stories and Karrie Fransman’s The House that Groaned take that to a very local level.

Steven Walsh, the man at the helm of London’s treasured Gosh comics, picks out Eisner’s work. “He may well be the greatest chronicler of urban space in the history of comics – his gritty, grimy streets streaked with steam rising up and shadows carved across the looming buildings,” Walsh says. “Much of Eisner’s work was concerned with people feeling overwhelmed or powerless, themes that are well suited to the populous anonymity of the city.”

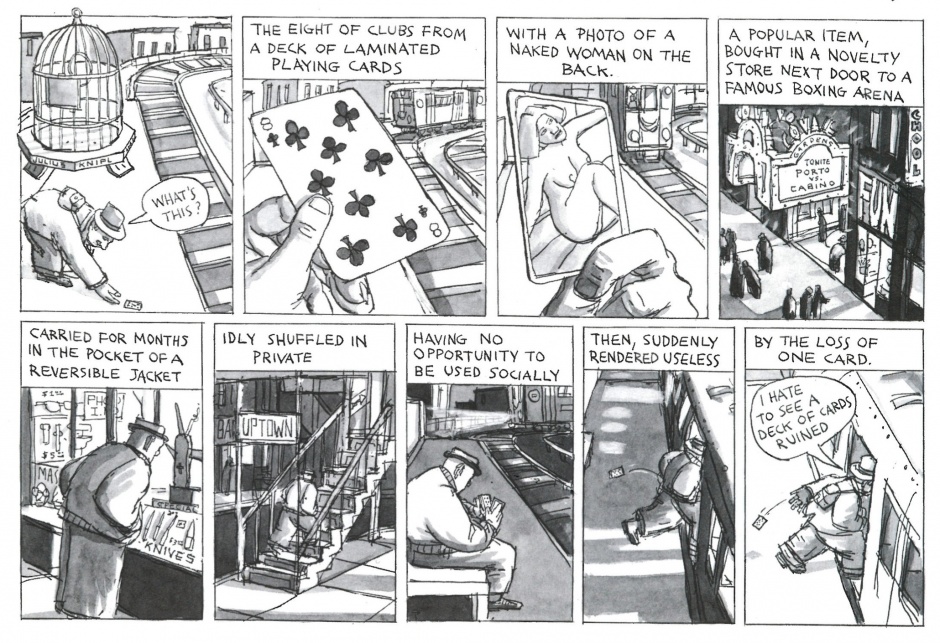

A more gentle impression is made by the Ben Katchor strip that maps the movements of Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer. Knipl is a genial creation: a rotund, wide-trousered chap in a hat, who accepts commissions to take photographs of buildings in an unnamed city. The objects and buildings trigger old memories for Knipl, so while his photographic eye is cooly detached, surveying the present, his emotions about the past emerge through a witty, drip-fed commentary. In one episode from Cheap Novelties: The Pleasure of Urban Decay, Knipl picks up a playing card from the pavement. “What’s this?” Then, in barely 50 words and eight panels of pen-and-ink, he gives a meditation on the social bonding that cards represent. “I hate to see a deck of cards ruined,” he concludes, as the train doors close. In an interview with Katchor for his weekly Panel Borders podcast, Alex Fitch touches on the feeling of loss in Knipl; but Katchor explains he isn’t criticising modern architecture so much as the absurdity of the built world – the disconnect between the people that construct it and the people that use it.

I asked Katchor about the fictional cities he likes to hang out in. “I love to visit the imaginary midwestern city of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy comic strip and the ‘New York’ of Harry Hershfield’s Abie the Agent,” he says. “The object description, the line quality and the language used by these artist-writers produces these unique and palpable environments. Gould’s city has a cool, brutual angularity. Hershfield’s New York is a early 20th-century city of Yiddish-tinged English, cosy interiors and wild business schemes.”

Knipl’s city is designed to be as old as New York, but not New York. It’s a city for everyone. “It shares many of the social and economic systems of a city like New York City,” says Katchor, “but they are completely different in the particularity of their details. I try to avoid generalities or universals. The approach is one in which the assemblage of the city (buildings, objects, etc) has an impact upon the thoughts of the people – it colours their dreams.”

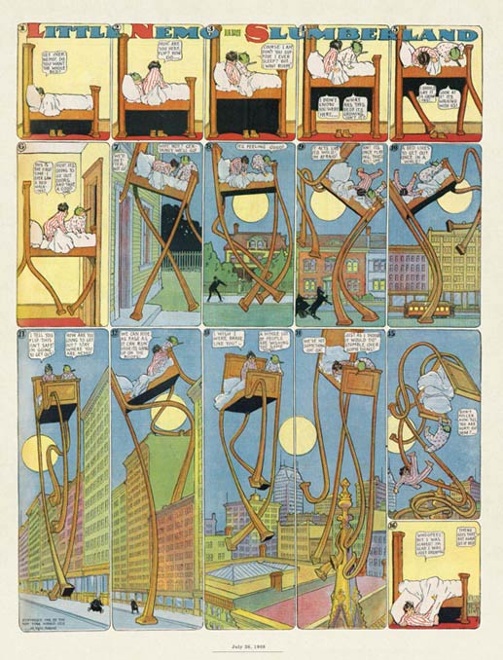

No one’s dreams were more coloured by the city than Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, one of the earliest US strips, which ran in the New York Herald from 1905-1911. As he falls into a fantastic sleep, Nemo’s cot grows legs like a giraffe and he strides, almost Godzilla-like, through fantastic, sky-scraping scenery inspired by McCay’s memories of city expos and theme-park rollercoasters – a kind of fantasy architecture. It’s the architecture of the page, though, that McCay was most radical with. Nemo didn’t just reach across the page, but down it, in dizzying vertical panels that knocked out the supporting walls of the old calendar-like “waffle” of the comic.

There’s a wormhole you can travel through, straight from Nemo’s dreams, back in the early 20th century, to Dean Motter’s 2001-2 Electropolis (“Yesterday’s City of Tomorrow“), a retrofuturistic mash of mile-high skyscrapers, Zeppelins and Van Der Graaf generators that imagines 1999 as it was predicted to turn out back in 1939. Here is a curdling of past and future. As Motter’s own site says: “From the air the city resembles nothing so much as the interior of an old radio or television set. Machinery as architecture … Electricity as commerce … Electropolis is a vintage murder mystery involving Menlo Park, the electric detective.” (And while we are in the precinct of detectives and floating cars, mention must be made of The Long Tomorrow, written by Dan O’Bannon in 1975, illustrated by Moebius – a cyberpunk story whose visuals unmistakeably influenced Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.) That corridor between past and future is arrestingly revealed in one of the most famous graphic novels to be set in London, From Hell, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s speculation on the motivations of Jack the Ripper. In one arresting panel we see the Ripper (William Gull), bloodied knife held high, beholding a vision of the Nat West tower.

More often, though, it is the past that haunts. FreakAngels, written by Warren Ellis and drawn by Paul Duffield between 2005 and 2011, involves, as Ellis puts it, characters with a range of special abilities such as telepathy “living in a post-flood London that they might possibly have had something to do with”. For Duffield, London is a character – a kind of ghost. “Seeing so many recognisable landmarks and streets confronts any reader who is familiar with the city with a constant sense of what has been lost and what used to be,” he says. “I think there’s also an interesting twist on this ‘ghostly” element of the city – while certain landmarks remind us of what was, they are also repurposed in a more immediately human way. Spires become watchtowers, the top of pubs become gardens, churches become secular gathering places. We interact with them through the comic in a much more intimate way than we ever interact with them as residents or tourists. In this respect, the city can be seen as a space in which the environmental changes of the story can be instantly understood – a sort of visual narrator.”

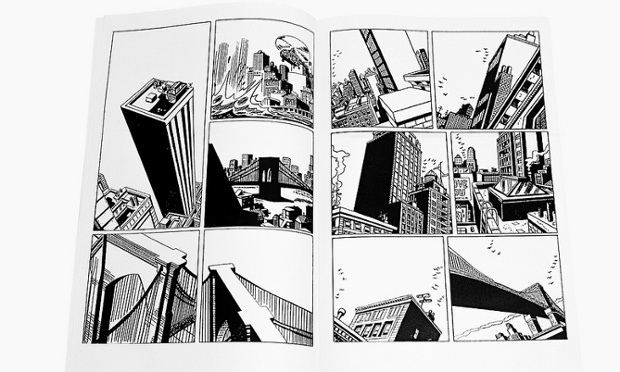

The city literally becomes the protagonist in Stuart Bannocks’s City Strips, which take stories from well-known comics, such as Spider-Man and Batman, and remove all the characters and the dialogue. The result (which echo the Garfield Minus Garfield strips, which erased Garfield from his own world) are what Bannocks calls “all action architecture from some of the most read cities of fiction earth“.

Some works are more concerned with reality. Although Joe Sacco’s early comics are fictional, he eventually fused journalism, illustration and travel to produce celebrated reportage such as Palestine, The Fixer and Safe Area Gorazde – books that seem to smuggle you into a city as much as simply reporting on it. Similarly, Guy Delisle has sought out conflicted places such as Pyongyang, Shenzhen and Jerusalem, relating his experiences as graphic novels. Equally, at the other extreme, there are comics that stretch beyond any practical possibility, where you find yourself dropped into Escher-like mazes, places in which the comic itself becomes the city. Norwegian artist Terje Brofoss, AKA Pushwagner, conjures a dystopian suffocation in his graphic novel Soft City, with its large pages packed with repetitions of windows, people and vehicles stretching to infinity. These expansive A3 pages, filled with spidery lines, make me think of the Total Perspective Vortex in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: a vertiginous reminder of how insignificant we are in a colossal repetitive universe.

Everywhere you look, being trapped is a theme. Greg M Smith, a scholar at Georgia State University, says that for Will Eisner “comics form a catalog of how architecture can become a frame and how these frames can become prisons”, so it is fitting that in Marc Antoine Mathieu’s Acquefacques, the protagonist Julius Corentin escapes his “prison”, and can be seen reading the comic that he is in (that is, the same one you are reading) or walking along the dividers between the panels, looking down into the boxes on either side of him as if they were office cubicles. As Mathieu plays with the grid of the comic book page, he reveals one of the reasons this art relates so well to the city, itself a multimedia grid of hoardings, billboards and shop windows that squabble for our attention – and turn our gaze into that of the wandering “flaneur”. Eisner was all too aware of this, and a warning he makes in his book Comics and Sequential Art, written in 1985, has only snowballed in relevance: “The most important obstacle to surmount is the tendency of the reader’s eye to wander.”

Is that wandering eye how we take in cities? Duffield agrees that the grid of a comic page is very well suited to portraying built-up cities, but warns of thinking photographically. “Creating the sense of a place is often about more than just picking a camera angle and pressing the virtual shutter button,” he says. “Such an image can’t be the entirety of place, only ever the place as seen from one vantage point. It’s interesting to think about ancient illustrations of cities, before literally represented perspective was the norm in the visual arts. Such illustrations aren’t ‘realistic’, but perhaps they better represent the internalised impressions we have of the places we live, which are jumbles of memories instead of a series of images recalled with photographic fidelity.”

Grids of images, stacked floor by floor … comics are miniature apartment blocks that we peer in to, like the chair-bound Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window. It’s not just what happens in those windows that’s of interest, either. Buildings hide as much as they show, and as Scott McCloud suggests in his Understanding Comics books (themselves in comic-book form), lots of mischief takes place in those spaces between the windows. This, he says, is where the reader becomes implicated, no longer an innocent bystander. In McCloud’s mind, if a comic book shows an axe raised above a head in one panel, and a decapitated corpse in the next, there’s only one person who joined the dots – one person who committed the crime: you.

Well, that’s probably the most benign place to indulge your inner super-villain. Comics reflect the cities we live in and the effect those cities have on us – as well as the cities we build inside ourselves. Just be prepared to face the men in tights, or else move to the country, where Spider-Man can’t get a grip.

This feature originally appeared in The Guardian.