While helping others is a powerful motivation in the early stage of migrants’ and refugees’ arrival, it is not a good basis for genuine integration. Institutions should help refugees build social capital and agency in their cities.

Souad has a medical degree from Syria. She arrived in Germany in 2015 but found it difficult to find a job in the health field. In the first weeks and months after the end of her dangerous journey, she was filled with both relief and anxiety: Will she ever fit into her new environment? Will she ever lead a normal life and cease being “the refugee?”.

Life was scary and lonely at first but eventually, thanks to local NGOs and clubs, she met other women who were not just relief workers and refugees. She also began learning German in a social context, which was a welcome change from the dry, sterile manner of language classes. Staff and volunteers at the ‘refugee hotel’ where she first lived helped her with the paperwork, residents permit, finding schools for the children, booking hospital appointments and advising how she could ask for her qualifications to be assessed and recognised – not a straightforward process, as she quickly understood.

From our partners:

Her children attended welcoming classes – a long-standing institution in Berlin schools which is now inspiring others in Germany, a country where most schools are unaccustomed to diversity. Many offices, cafes, NGOs that display the sticker “Refugees welcome” gave her the courage to open the door and step in, overcoming her own fears and lack of linguistic and cultural fluency.

She engaged with the “Voice Refugee Forum” network which strives to give refugees dignity and a true place in the community as citizens, not as victims.

While helping others is a powerful motivation in the early stage of migrants’ and refugees’ arrival, it is not a good basis for genuine integration. If in the long term everyone sees you only as a person in need, this makes you doubt your capacity to succeed and gain agency in life. It is ultimately dehumanising.

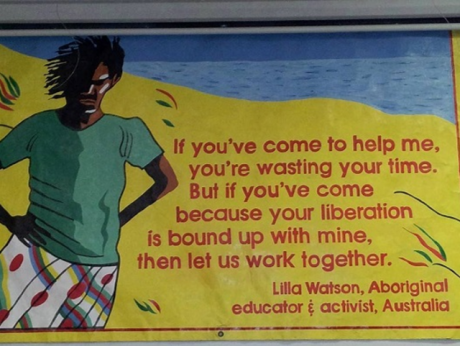

The Voice Refugee Forum express their mission through the words of Lilla Watson, Aboriginal activist in Australia: “If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

These words hold an amazing wisdom: human connections sometimes start with compassion and empathy. But a long-term relationship cannot thrive on this basis alone, or it will become pathological. Similarly, when welfare, education, support institutions operate from a place of pity, not potential, they do not empower but perpetuate inequality and subordination.

The goal of support institutions should be to build and maintain social capital – the dense network of relationships which forms the backbone of a functioning society. Social research has proven that the density of such network is at the core of all societal well-being – from health, to safety, creativity, longevity, economic growth and personal happiness. Human networks are powerful because individuals forming them are interdependent – each human brink brings value and none is subordinated to the other.

Networks emerge organically of course but people naturally gravitate to those who are like them – culturally and socially. It takes longer for networks to form organically across greater cultural distance, or when large groups of stranger move into existing communities. People need reasons to connect to others beyond their comfort zone. There are many barriers – in the way our cities are built as physical spaces – which make such interaction difficult. Left alone, human communities often segment and fraction alongside division of kinship, language, faith and social class, leading to segregated neighborhoods and schools.

When human mobility accelerates as in our globalised age, we need to invest in the social infrastructure which will increase communities’ capacity to overcome the natural resistance to difference and form a dense fabric of relationships across these natural dividing lines. In very practical terms, this means that we need more civil society organisations and sports clubs, community and women’s groups, interfaith councils and neighborhood fests.

We need more intercultural competent community developers and mediators, as well as police officers, social workers, teachers and civil servants who act as node in purposeful networks that nudge people into positive, productive, creative, trust-building interactions and relationships. Providing the resources and the framework for this work is a new but already indispensible task for public authorities, and in particular cities.

We need more Anti-rumours campaigns which help lower barriers to cross-cultural relations by telling the true story about migrants, their impact on society, their aspirations and lives, to create a positive human dynamic.

Our liberal democracies have been built upon the concept of equality of all human beings – a concept which in its legal interpretation is fundamentally individualistic and rights-based. If we are struggling to make equality a daily reality because we have invested very little in the understanding and practice of relational equality – the one that makes treats the other as equal because we experience the value they bring to our lives. Only this kind of experiential equality can ensure the sustainability of rights-based equality.

Cities are the places where relational equality forms and operates, even more so in societies where cultural diversity increases social distance and barriers to interaction. The intuition of the original Intercultural city research by Phil Wood and Charles Landry which underpinned the Intercultural cities programme of the Council of Europe, was that in times of intensive human mobility, cities need to purposefully take up the task of nurturing relations and building social capital across cultures. After almost 10 years of developing and putting this intuition into practice in partnership with 120 cities across the globe, we have solid research evidence that the intuition was correct, that the Intercultural approach to integrating diverse societies yields results.

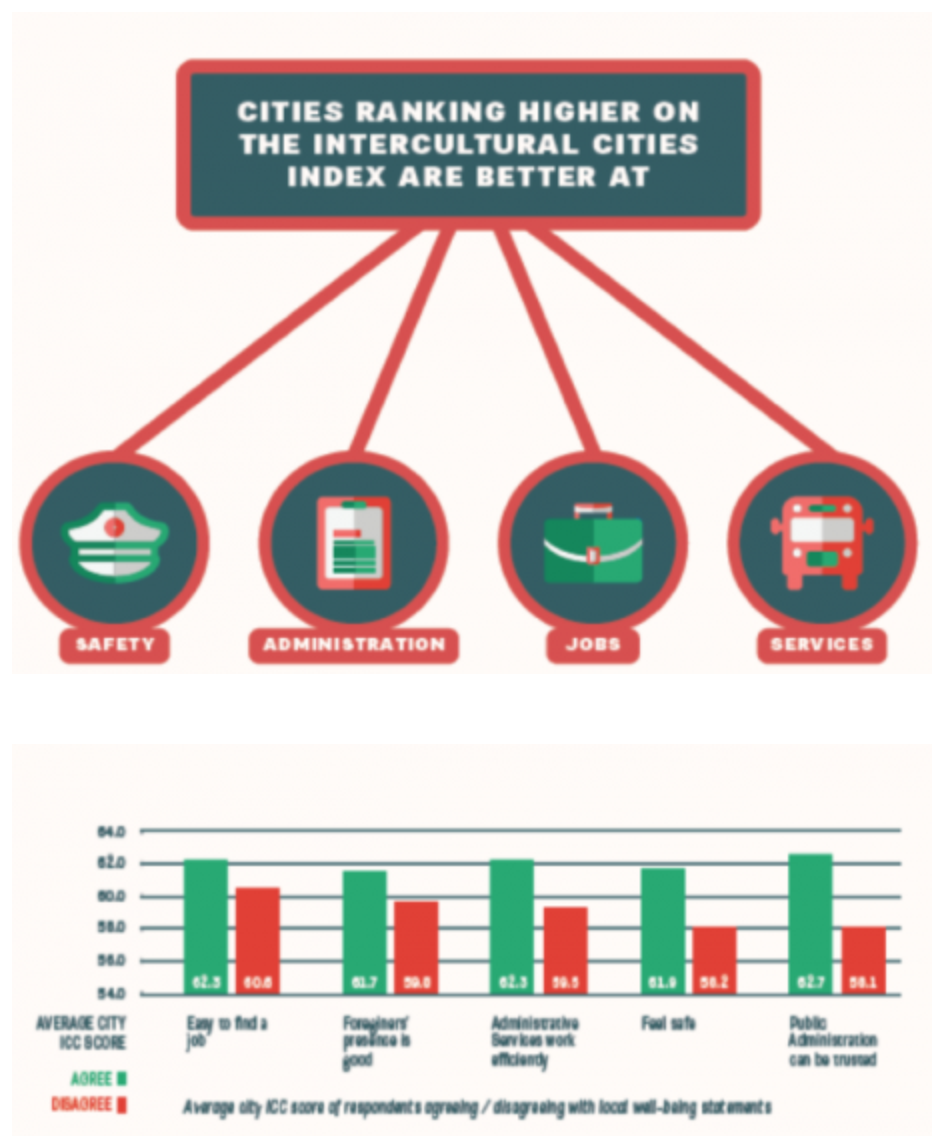

A study released in November 2017 (see summary of the results) by the Migration Policy Group focused on the interdependence between the adoption of the intercultural integration approach by cities and citizens’ perceptions of quality of life. Its conclusion was that in cities with stronger intercultural policies the majority of people had positive attitudes to migrants, thought that their city was safe and good for finding jobs, the presence of immigrants was good and services were trustworthy and efficient.

The study also found that local intercultural policies are the strongest factor for local well-being, just as significant as citizens’ age or education level, and more significant than national policies. Co-designing inclusion/integration policies with local and national authorities is likely to improve overall policy results on inclusion.

The future of cities is certainly diversity – managed in an intercultural way.

This article is written by Irena Guidikova & originally appeared in openDemocracy.