For centuries, people have lived in caves and tunnels under this region of Turkey. Now the subterranean city is serving a new purpose – as storage for vast quantities of agricultural produce.

The 98 square kilometres of the Cappadocia region in Turkey make for a strange landscape. Powdery white soil gives the place a lunar feel. The hollowed out hillsides and 10-metre tall “fairy chimneys”, a tourist attraction crafted by wind and rain, could be leftovers from a 1970s James Bond set. At night, lights flicker in the cones of rock, which hundreds of people call home.

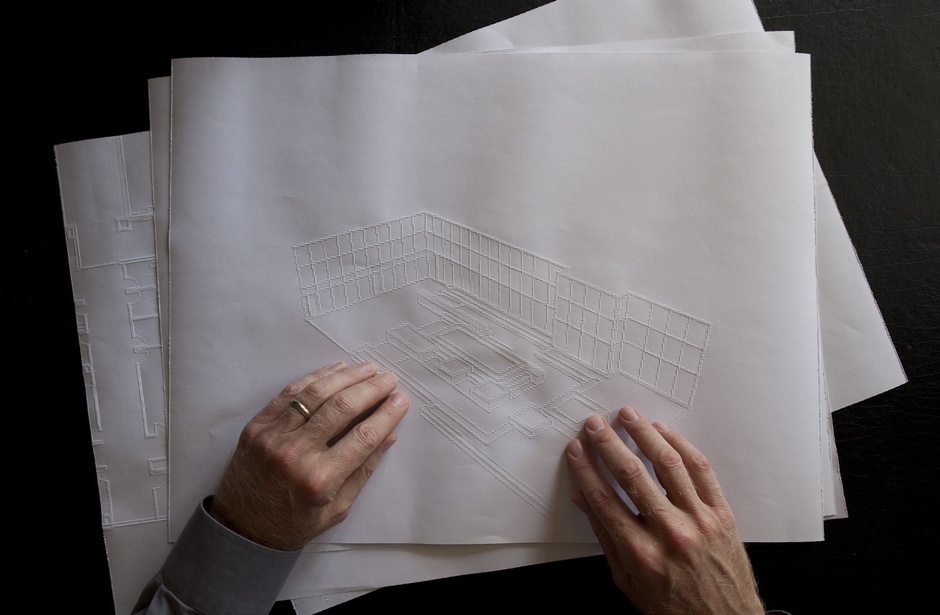

Beneath the earth, however, things look even stranger: a network of caves, connected into what used to be entire subterranean cities. Derinkuyu, in southern Cappadocia, was once home to as many as 20,000 residents living together underground. There’s a huge bathhouse, complete with a set of private rooms and tall ceilings to allow steam to rise, all of it ventilated by a system of shafts that run for dozens of kilometres in every direction – sometimes a vast distance from the populated areas to trick potential invaders.

Long abandoned, the underground cities of Cappadocia have rather suddenly been rediscovered: by the produce industry. The constant underground temperature of about 13C make the caves an ideal storage climate for thousands of tonnes of fruit and vegetables: apples, cabbage and cauliflower stay fresh for up to four weeks; citrus fruits, pears and potatoes for months. In a cave near the village of Ortahisar, nearly 6m crates of lemons sit in endless stacks. They arrive from Turkey’s Mediterranean coast on trucks and are unloaded by hand. Labourers – mostly women – package and stack the fruit, which then is stored underground until it is needed for export to Europe, Russia and elsewhere.

Okan Yazgan, who runs the Aravan Evi hotel here, has taken advantage. “We have a cave store with a capacity of 100 tonnes, but we do not have a large enough area for growing potatoes. So we rent our store space,” he said. The potatoes are stored underground and sold in situ when prices increase during winter and spring, Yazgan added.

From our partners:

The volcanic rock of these underground cities is moist and soft to the touch – a car key or pen easily leaves a mark – and the walls carry the marks of its former residents. Small ridges can be seen on the walls and ceilings, made as long as 3,500 years ago by the first people to realise that they could chisel out a home here. They liked living underground for much of the same reason that the produce vendors do: when visiting Cappadocia in 400 BC, Xenophon, a student of Socrates, reported seeing goats, sheep, cows and poultry fed on straw and hay. “Corn, rice, vegetables and barley beer was stored in large pots,” he wrote.

Could other cities learn from Cappadocia’s example? Berlin is home to many kilometres of underground tunnels and rooms, built in the second world war to protect against bombings; Switzerland has enough underground space to shelter every citizen in the event of nuclear war. Singapore, meanwhile, is planning to use a 150-acre cavern under the city to store fuel and build a facility for scientists and researchers. Although cities that don’t already have underground space would likely see limited benefits – meat and frozen foods certainly would require the refrigeration only fridges and supermarkets freezers provide – Nikolai Bobylev, an environmental scientist at Saint Petersburg State University, says underground urban space is an overlooked resource.

“We can use underground space for all the urban services that do not require daylight – transport, waste management, retail,” he says. “Thus we can save pressure [on] above-ground space for living, recreation, greenery – creating compact and more sustainable cities.”

In Cappadocia, some of the underground warehouses have a capacity of 20,000 tonnes, but the financial incentive is proving irresistible: local companies and those in the produce business have begun carving out new caves in the rock, and international companies such as Frito Lay are reported to be planning to invest.

Thousands of years since they were first created, the underground cities of Cappadocia are growing once again.

This article originally appeared in The Guardian.