Water as a liquid has no shape. It acquires definition from its surroundings, providing boundaries and edges to our landscapes while also connecting them.

How water is shaped, naturally or artificially, can distinguish it between a weapon-like tool (think of an industrial water jet cutter that can precisely slice through stone, leather, tile and steel) and a trusty, quiet, stationary park fountain (think of the ball fields where the push of a pudgy little thumb releases a soft, luscious pulse of cold water into a play-worn, parched mouth).

[infobox]“Fountain designers and hydraulic experts often push the limits of water’s physical properties. When creating fountains, designers consider how the water should move — with gentle insistence or raging force; how the water should sound — as a soothing trickle or as a surging splash; and how the water should look — clear and smooth or frothy and white.”— Symmes, Marilyn F, and Kenneth A. Breisch. Fountains Splash and Spectacle: Water and Design from the Renaissance to the Present[/infobox]

While it is easy to see how water can be shaped when it is used ornamentally or as a recreational or industrial tool, it is less easy to imagine the intricate subterranean design of pipes and valves that allow (some of) us to live pretty much where we please, confident that with a turn of a knob or a press of a button, we can summons potable water. Equally as hidden is the drainage of our on-demand water. We may briefly watch it swirl downward but then it slips into little holes and then, into darkness.

There are people who “daylight” these subterranean hydraulic mysteries — at least a few layers of them. Meet Emmanuel Thingue, drinking fountain designer and Larry Snyder, drinking fountain fabricator.

From our partners:

Emmanuel Thingue, Senior Landscape Architect with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, has thought more about drinking fountains than he ever imagined he could and, he admits, more than he’d like to. In the early 1990s, during the salad days of his civic career, Emmanuel unwittingly became the designer of what is now the most ubiquitous style of drinking fountain in New York City’s parks — an uninterrupted cast iron number that he originally designed for an upgrade of Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza.

As any good landscape architect would, Emmanuel’s research and early sketches of new site furnishings for Cadman Plaza were informed not only by the Plaza’s 1939 inaugural architectural tone and materials vocabulary, but also by its vandals, prostitutes and maintenance crew’s service registers from the 1970s and 80s.

“During our design research,” Emmanuel says, “we found that most city park drinking fountains were vandalized in one specific way — by knocking out the bubbler. That was the single, chronic, most destructive form of vandalism because once the bubbler is gone the entire piece of furniture housing the waterworks is completely useless.” And so out of the gate, New York City Parks was charged with creating a drinking fountain design that was indestructible, functional and elegant.

Protecting the bubbler became a preeminent design concern.

[infobox]Vandals unwittingly helped restore public drinking fountains to the field of landscape architecture where the mere suggestion of making them, I learned, goes over like a lead balloon.[/infobox]

Drinking fountains are a chore, a must, a functional necessity and a fundamental distraction to landscape architects’ more poetic callings. In my interviews, I found their creative and intellectual disinterest in (and there’s no sexy way to say it) public utilities infrastructure surprising since it has been the developments in design, architecture, hydrology and engineering related to public drinking fountains and private taps — the very domestication of water — that has directed human settlement patterns globally.

What’s more, for centuries, drinking fountain design has been a coveted job. Fountain construction was well-patronized and the presence of fountains in the landscape frequently bombastic, symbolizing civic and religious power as well as a nation’s technical acumen and wealth. With just around three percent of our planet’s water being potable and our species unable to survive without it, the way we shape water’s release matters.

It is worth remembering that New York City was, roughly 175 years before Emmanuel’s redo of the Cadman Plaza fountains, one of the first American cities (Boston was the other) to establish a reliable water distribution system for its residents — the Croton Dam aqueduct and reservoir system. Colonial settlers were convinced to establish this system only after 218 years rife with waterborne pandemics, ineffective wooden water pipes, flagrant corruption within privatized water companies, and the last straw — an inextinguishable fire (“The Great Fire of New York”) in 1835 that nearly leveled the city thanks to poorly designed and maintained public water fountains and hydrants.

So in 1990, with a modest city Parks budget (hell, the entire city was emerging from decades of near-bankruptcy), Emmanuel sought help in fabricating what would be a lasting urban drinking water fountain. He found Larry Snyder. And in Larry, he found a comrade from America’s second biggest city after New York—Los Angeles. They could speak bubbler bashing with street-smart ease and design from reality’s hard ground.

Larry Snyder has the kind of New York City accent I love — long-a’s and charmingly dropped r’s that suggest an interesting life. Born and raised in Manhattan in the 1930s (thereabouts), he left for Los Angeles soon after serving in WWII, where he picked up engineering, building and fabrication skills as a soldier. With a New Yorker’s irrepressible confidence, Larry founded Canterbury International in his adopted hometown. It is now the country’s most esteemed fabricator of public site furnishings.

“We designed many fountains before New York City Parks,” Larry tells me. “I think of drinking fountains as works of art. I’ve studied them on trips to older cities in Europe to understand the possibility of what they could be for communities today. There was more grandeur in the past though. Of course that was before ADA. None of those ornate, old fountains are compliant now.” When Larry received the call from Emmanuel, he understood what he needed. “I’m from Manhattan and I know New Yorkers like to destroy things!”

The fountain that Canterbury custom makes for New York City Parks is a very heavy-duty cast iron. Each fountain is a solid, “period-elegant,” one-piece casting made with ductile iron. Before applying a finishing seal, the entire iron fixture is cadmium-plated, then dipped into a molten zinc-tin combo ensuring that if the finish cracks, there is a protective coating below that won’t rust. The fountain bowls are either bronze or stainless steel. And lastly, the bubbler is housed in an iron sheath so that, as Larry says, “You could hit it with a hammer and you’re not going to hurt it.”

The NYC fountain — Canterbury

But shaping water and designing fountains is about more than outwitting the criminal mind or aligning the materials “vocabulary” of a public place. Shaping water into public drinking fountains rests on what is essentially universal common-law acknowledging our species’ need for water.

In the 1964 film A Fistful of Dollars, Clint Eastwood , in classic spaghetti-Western form, rides into a dusty town with his brim-dipped hat and dark wool poncho, his horse clip-clopping past bleached adobe houses. The first thing he does as The Man With No Name, is stop at the town well to get fresh water. Quenching his thirst is the one thing he can do anywhere in peace. Even in this epicenter of American Frontier barbarism, he will not be denied water.

“If a drinking fountain wasn’t located in a marketplace or town-center, in exchange for a few coins,” writes Marilyn Symmes, former Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum curator and editor of the book, Fountain: Splash and Spectacle, “water sellers provided a cup of water for those who needed a drink. There were also water carriers who transported barrels to homes far from their source. So vital was the water carrier’s role that they were occasionally immortalized, as in Rome’s Fontana del Facchino.”

[infobox]Following this idea that fountain design is driven by the basic human need for water and our almost instinctual impulse to share it, is geology. Geology shapes water, which shapes behavior, which shapes culture , which shapes law , which shapes religion , which shapes design (in some roulette order).[/infobox]

Our global deserts are a natural terrain to turn to when looking at the culture of shaping water. Ottoman, Syrian and Persian drinking fountains fill design canons because harsh equatorial and desert climates make water a highly valuable resource and a highly considered object of design.

Interestingly, as a point of entry into desert drinking fountain design, I discovered the writing of United Nations researcher Jarmo J. Hukka and Petri S. Juuti, Finnish Professor of Environmental History and Technology at the University of Tampere, who explain that, like in the Torah, “the Shari’ah, goes into great detail on the subject of water to ensure the fair and equitable distribution of water within the community. No one can refuse surplus water without sinning against Allah and against man. And, also like the etymology of Torah, Shari’ah means path to the watering hole.”

Landscape-archaeologist Avi Sasson also explains that in ancient Jerusalem, providing water to travelers via sabils (kiosk-style drinking fountains) “was so important that Turkish authorities would grant tax exemptions to anyone who privately built a sabil for public use, on condition that he ensured that water would always be available for travelers.”

It wasn’t just the desert-dwellers who encouraged public drinking fountains and discouraged privatization of water. The Roman Catholics were grand public drinking fountain patrons, as were many aristocrats who knew their hold on power relied on an attention to The Commons.

Yet as hydraulic engineering evolved and potable water became increasingly domesticated across classes and landscapes, the role of The Commons in providing drinking water shifted. The role of architects in designing public drinking fountains was also adjusted to meet a decrease in demand.

[infobox]Landmark civil rights regulations like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) have altered public drinking fountain design practices and inspired innovation, but the most significant catalyst that has restored an interest in public drinking fountain design has been the plastic drinking water bottle.[/infobox]

Plastic water bottle sculptures created for Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development

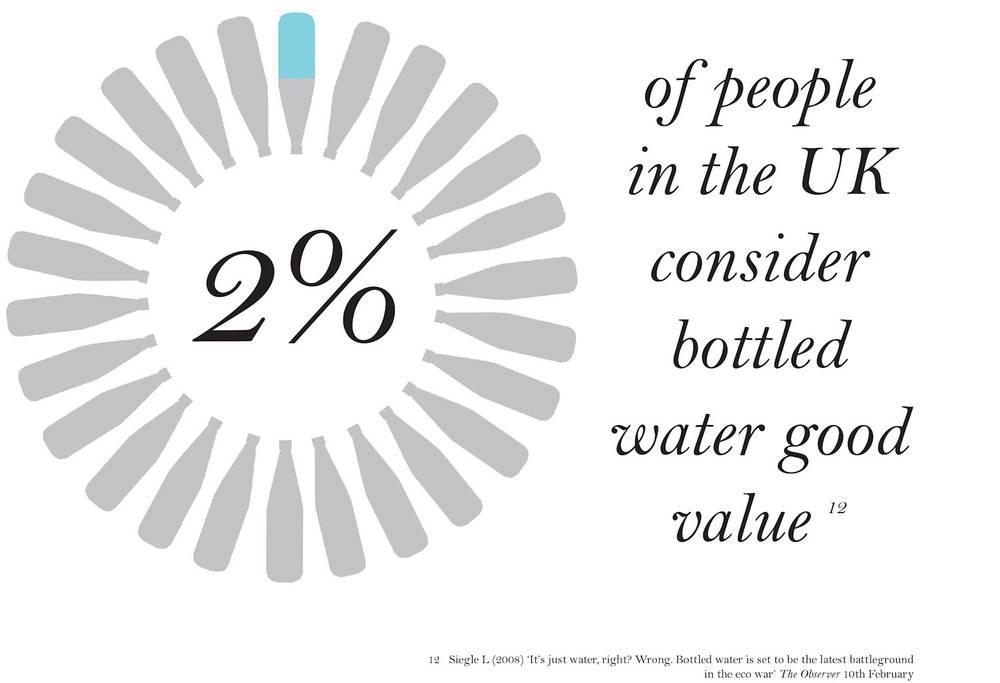

Alarmed by climate change, colossal plastic marine debris and the sheer regressiveness and irrationality of paying for a public utility and then paying for it again in the marketplace has inspired a new generation of 21st-century public drinking water fountain designs.

While in London for work two summers ago, I met up with architect Je Ahn at his Studio Weave in Hackney to talk drinking water fountain social history and a possible joint project in New York City’s Central Park.

As luck would have it, while Central Park Conservancy turned a disinterested ear, the AJ Kiosk Challenge (Architects Journal) was launched, commissioning concept designs for a 21st-century drinking water fountain. Studio Weave, Zaha Hadid, AHMM and three other firms participated. Studio Weave created Watering Poles, picking up and playing up the irrepressible, timeless universal culture of “watering holes.”

The strong legacy of understanding the art of the commons, and the drinking fountain’s central role in them, is returning—triumphantly, colorfully and sustainably. In an era of inclusive and environmentally-attentive design, the specs and forms may change, but the brief is the same: to quench the thirst of every passer-by.

This feature originally appeared in reform at Medium.