Much of the international community has condemned Russia’s annexation of four provinces of Ukraine as illegal. Joe Biden accused Vladmir Putin of a “fraudulent attempt” to claim Ukrainian territory and said the move was “trampling on the United Nations charter, and showing its contempt for peaceful nations everywhere”. The UK’s human rights ambassador, Rita French, denounced Russia’s move in the UN’s human rights council as “an unprovoked and illegal land grab of sovereign Ukrainian territory”.

Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, described the west’s condemnation of its actions as a “temper tantrum”, adding that “any sovereign, self-respecting state that realises the responsibility it has to its own people would do the same”. But the US ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, said the annexations – if allowed to stand – would “open a pandora’s box that we cannot close”. To get an idea of the stakes involved, it’s worth looking at the historical record.

Russia’s annexation of these territories is very unusual, at least since 1945. Almost never has a state conquered by force and then annexed a large populated territory like that in Ukraine. And the few times it has happened, the international community has almost always come together in not recognising the situation.

When Indonesia invaded and occupied East Timor in 1974 it was condemned and Indonesia’s claimed sovereignty was not recognised for decades. Eventually a democratic, UN-sponsored referendum produced the new independent state of Timor-L’este in 2002.

Territories occupied by Israel in 1967 and the northern part of Cyprus occupied by Turkey in 1974 have remained unrecognised for decades. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 is another notoriously unrecognised example of an illegal landgrab.

From our partners:

The direct material effect of non-recognition is close to nothing – especially compared to imposing economic sanctions on Russia or providing Ukraine with weapons and equipment. But what non-recognition can do is reassure everyone that the international community values a world without aggressive war.

So what if Russia is allowed to keep these territories – perhaps as part of a peace negotiation? Putin has stated that peace talks can now start but that the annexed areas are not on the table. If Russia gains rights over these territories (as well as in Crimea) because it conquered them in battle, and these rights are accepted by the international community, then the relatively solid expectation that illegal warfare conquest doesn’t pay is likely to evaporate.

How do we know this?

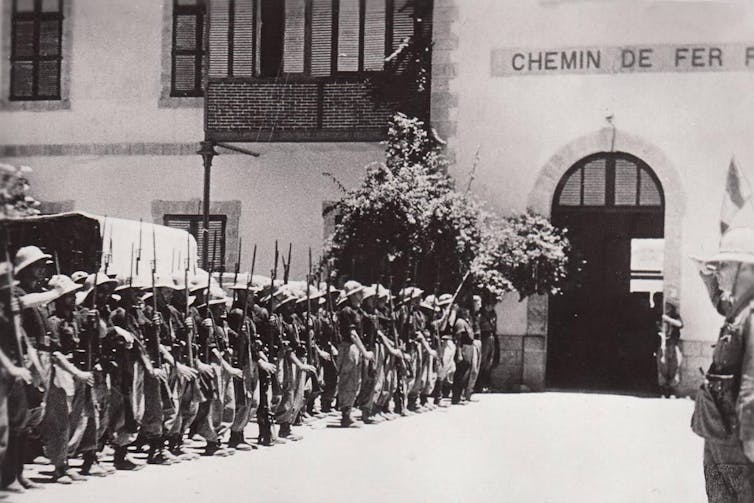

In 1935, Italy under the leadership of Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia. The League of Nations – and the US – condemned the invasion, declared support for the territorial integrity of Ethiopia and coordinated economic sanctions on Italy. But the foreign ministers of Great Britain and France reached a secret agreement with Mussolini to end the war.

This involved Ethiopia ceding most of its territory to Italy and handing Mussolini economic control over the rest of the country. Instead of defending Ethiopia against aggression, the UK and France tried to trade its sovereignty for an end to the war.

Wikimedia Commons

When this agreement became public knowledge, people around the world failed to appreciate this plan as a prudent acceptance of political realities. Instead, they thought that Italy, an aggressor state, was being rewarded for victories on the field of battle, a betrayal of the principle of opposing aggression.

The reaction was so negative that the UK and French governments abandoned the proposals and Hoare and Laval resigned in disgrace. Nevertheless, a month later, the US dropped its arms embargo against Italy and the League of Nations voted to end sanctions. Even though the US, the Soviet Union and a few other states refused to recognise Italy’s empire in East Africa, it was enough that the consensus was broken.

Some states, including Honduras, Nicaragua, Chile, Venezuela, Spain and Hungary left the League of Nations completely in response. A group of smaller European states, including Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Belgium said that they would no longer participate in the League’s collective security.

Remaining states, such as the UK and France, decided to try a newfangled policy of appeasement as a way to deal with aggressive states. The theory was that if you gave into states with demands, such as Germany under Hitler, they would then leave everyone alone and be responsible members of international society. What the failure of collective security in the Ethiopian crisis did was to remove collective security from the menu of options considered serious tools to deal with Italy and Germany.

Non-recognition is essential

The lesson from these historical precursors is that upholding the principle that conquest does not pay is potentially sustainable indefinitely. The division of Cyprus into the Republic of Cyprus in the south and the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is coming up to its 50th anniversary in November 2023. The north is still unable to trade with the EU because of the legal barriers created by non-recognition.

Non-recognition is essential for maintaining the existing consensus that success in battle should not confer rights on the victor. Without non-recognition, the will to protect the current relatively peaceful global order might evaporate like it did in the 1930s.

If Russia is allowed to keep the territories it has occupied by force of arms, a similar situation might develop as aggressors are encouraged and smaller countries feel the need to rearm themselves. We have already seen Finland and Sweden sign accession deals with Nato, which will immediately involve Nato bases moving closer to Russian territory.

Success in the field will send a message that might is right. This would not bode well for a peaceful and secure future.

Joseph O’Mahoney, Associate Professor of International Relations, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.