We would like to thank our generous sponsors for making this article possible.

Is the semiconductor crisis finally over?

- Some chip shortages could remain through 2023 and into 2024, though supply of semiconductors and raw materials will generally improve in the auto sector.

- The auto sector can expect a strong year in 2023, with global car production up 3%.

- As semiconductor supply returns, global auto pricing should remain stable.

The chip shortage is all but over, according to J.P. Morgan Research. In fact, there may even be oversupply in the short term, though looking further ahead, some shortages could linger as certain types of chips remain more in demand than others.

Semiconductors or chips are a crucial element in the manufacturing of consumer electronics such as smartphones, cameras and computers. In cars, they are needed for everything from entertainment systems to power steering. At the height of the chip shortage, global auto production slumped 26% during the first nine months of 2021. Find out why chip shortages heavily impact the auto industry and what lies ahead for 2023 as the outlook improves.

What’s next for the auto industry as supply chain issues fade?

“2023 should mark a strong earnings year for the industry, with less volatile raw material costs and a more stable supply chain,” said Jose Asumendi, Head of European Automotive Research. “Raw material headwinds will slow, eventually providing a tailwind sometime in the second half of 2023. Overall, we predict a strong year for the autos sector, with global car production up 3% year-over-year.”

From our partners:

There is likely to be less earnings volatility in 2023, with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) maintaining strong pricing power. Equally, more stability should boost the earnings momentum of suppliers and make this a stronger year across the board. “We anticipate tight control over inventories, which maintains pricing power for OEMs and reduces the likelihood of rising incentives,” added Asumendi. “Overall, we expect a more stable pricing environment.” In terms of demand, OEMs expect some normalization, which is not unusual moving away from a period of extraordinary demand and low supply.

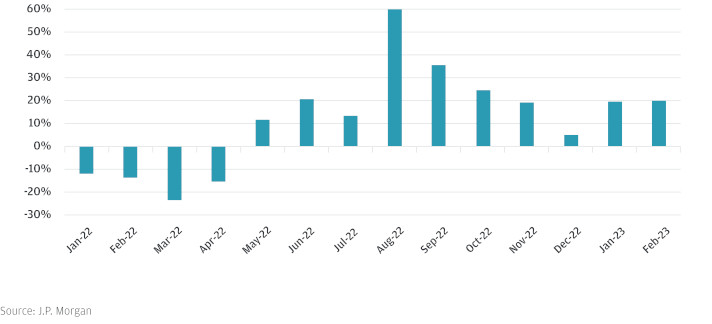

Europe remains the weakest region for production, particularly compared with North America and China, where there has been stronger recovery post-2020. The region has been the hardest hit by supply constraints linked to semiconductor shortages and the Russia-Ukraine crisis. However, production is showing signs of improvement. “Counterintuitively, we now expect Europe to show the strongest growth rate globally in 2023—we anticipate 5% year-over-year,” said Asumendi. Strong growth rates in January and February confirm supply chain stability is returning following the constraints of the past three years.

European auto production volumes in 2023 (year-over-year)

Will the chip shortage remain in the past?

We’re nearing the end of the supply crunch after more semiconductor capacity came online in 2022 … Looking ahead, we don’t predict any major constraints.

Sandeep Deshpande

Head of European Technology, J.P. Morgan

Chip supply began to improve in 2022 and looks set to continue through 2023. Capacity was initially freed up due to weakness in some end markets, particularly PCs, smartphones and consumer electronics, where sales began falling in March 2022. Foundries in Taiwan reallocated some of this capacity to the automobile and industrial end markets, which lost out to other sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, automakers are increasingly requiring chips with higher computing power—especially as the industry transitions to electric and autonomous vehicles—which are fundamentally different to those used in PCs and smartphones. “Capacity still needs to be qualified for use in the automotive industry. Can the right matching occur between available supply and correct qualification? This is the difficulty that remains, though we don’t predict any major constraints,” said Sandeep Deshpande, Head of European Technology Research at J.P. Morgan. “We’re nearing the end of the supply crunch now after more semiconductor capacity came online in the second half of 2022.”

What caused the 2020 chip shortage?

In the simplest terms, the chip shortage was due to strong demand and no supply. This goes back to COVID-19 lockdowns in the second quarter of 2020, when demand for work-from-home technology increased exponentially and automakers found themselves competing for the semiconductor capacity in Asian foundries. These supply chain issues caused upheaval in the auto industry, holding up production and denting sales.

Adding to the problem, downstream operations in South and Southeast Asia were adversely impacted by the COVID-19 Delta variant, creating further bottlenecks in the supply chain. Malaysia in particular performs many “back-end” operations such as chip packaging and testing, which are more labor-intensive than wafer fabrication processes, so activity is more easily affected by public health measures.

At the beginning of the pandemic, car companies canceled orders, but as production ramped up again toward the end of 2020, there was no semiconductor supply available. This was compounded by increased demand particularly at the higher end of the autos market, as low interest rates aided affordability.

While the COVID-19 pandemic was the initial catalyst for the chip shortage, structural factors were also part of the picture. Fundamentally, the auto industry is changing, with a major shift toward automation and electric vehicles. These require yet more chips, causing further strain on an already stretched industry.

Originally published at: J.P. Morgan