One of the first thoughts Danna Masad had about the importance of architecture occurred to her in early 2002, during the Second Intifada. A period of intense Israeli-Palestinian violence rife with military incursions, daily checkpoints, suicide bombings, anger and political hopelessness, it was a surprising moment for a young Palestinian woman to have a career epiphany.

At the time Masad volunteered with the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, a local arm of the International Red Cross. “Ramallah was under siege and I remember entering cold concrete houses, which were covered in mold, and families living in the most dire conditions,” she recalled in crisp English. “Why were we building in this way?”

Before that, in late 1990s, Masad studied in Palestine’s most prestigious architecture program, at Birzeit University north of Ramallah. Every day she would drive from Ramallah to Birzeit — a trip that should have taken 10 minutes, but stretched to an hour due to an Israeli checkpoint — weaving through a landscape of informal architecture that is biblical and congested at the same time. The haphazard urban layout situates the buildings in strange ways. Twelve-story apartment buildings cling dangerously to steep hillsides covered in ancient olive trees. The Birzeit campus reflects this tension, sitting like a fortress with lines inspired by Soviet architecture.

After finishing her bachelor’s degree amid the simmering conflict, Masad moved to California to get her master’s in architecture from California Polytechnic State University. In 2009 she returned in Palestine, somewhat disillusioned but ready to change the way its cities were being built. To her surprise, others had the same idea.

Masad is part of a generation of Palestinians who came of age during the violence, political infighting and restricted movement of the Second Intifada, which began in 2000 and lasted for roughly four years. In 2007, the New York Times called her and her peers “generation lost” in an article about their dim prospects for professional or political opportunity. “To hear these young people talk is to listen in on budding nihilism and a loss of hope,”Times correspondent Steven Erlanger wrote.

From our partners:

Yet after talking with Masad, one is left with a very different impression.

Far from the “lost generation,” Masad and her peers are embracing sustainable urban design with the notion that breaking out of never-ending fighting and occupation may require building a better way forward. The movement cuts across ethnic and political lines. It includes Israelis, Palestinians and international supporters from across the world.

In East Jerusalem, for instance, a young Israeli named Micha Kurz is working around the political quagmire to build a more livable reality for Palestinians and Israelis. Through his European Union-funded non-profit Grassroots Jerusalem, Kurz is attempting to make communities cleaner, safer and easier to navigate — without counting on the mythic day when the occupation ends. In the small villages dotting the West Bank, Sahar Qawasmi, with her non-profit Riwaq, is working to bring life back to historic Arab downtowns ignored during Palestine’s foreign-funded building boom.

Though small in number, these advocates are part of a larger movement seeking a greener and more open way of life in the increasingly urban Middle East. In the absence of a working peace process — or perhaps in defiance of a working peace process — they are sidestepping formal political channels to make change in neighborhoods and people’s homes. Within this honest assessment of a deadlocked political situation is a shred of hope for the region’s civic future.

“Our studio and others working on issues of urban design are trying our best to show people that we can be sustainable,” Masad said.

NOWHERE TO GO BUT UP

Ramallah, the de-facto capital of the Palestinian West Bank and just 10 miles from Jerusalem, has seen incredible growth in the past 20 years. What was once a sleepy village is now a crowded, booming capital city accommodating hundreds of thousands of people during workdays. According to the Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics, the greater Ramallah area in 2013 has an urban population of 170,000 people and a rural population of slightly less than 140,000. But on any given weekday, the city struggles to deal with the number of people pouring from all corners of the West Bank. Mind-numbing traffic jams are frequent and pedestrians fight to navigate crowded sidewalks. With each new season, Ramallah feels as though it is shrinking ever more under the pressure of Palestine’s population boom.

Yet the city’s downtown remains surprisingly small. Despite the crowds and traffic, the area contains little more than a single central market and a handful of streets connected by two traffic roundabouts, one of which was refurbished and renamed Arafat Square in recognition of the Palestinians’ successful bid to be recognized by the United Nations as a state. By six o’clock most evenings, the city’s busy demeanor transforms back to that of a sleepy village.

Salim Tamari, director of the Institute for Palestine Studies and an adjunct professor of contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University, blames the impending crisis largely on the explosive growth of Israeli settlements. “The main issue in terms of urban development on the West Bank is that there is confinement,” Tamari, an affable older man with bushy eyebrows, explained in his book-lined office in central Ramallah. Between sips of strong Turkish coffee, he explains Palestine’s quixotic urban geography, shaped by nearly five decades of Israeli occupation and the Oslo peace accords.

Signed in the mid-1990s between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Oslo peace accords gave way to interim self-government called the Palestinian Authority and divided the landlocked West Bank into three sectors: areas A, B and C. With various restrictions, Palestinians were given control over Area A, or about 18 percent of the West Bank’s 2,173 square miles. The rest of the West Bank came under shared Israel-Palestinian control or sole Israeli control, with 61 percent falling into the latter category. Today, more than half of West Bank Palestinians live on the 18 percent of land controlled by Palestinian officials.

[infobox]For these young designers, a more sustainable Palestine would be a political statement of independence and a solution to Palestine’s burgeoning housing crisis.[/infobox]While studying at Birzeit, Masad quickly realized that her coursework wasn’t preparing her to solve these problems easily observed in Ramallah. “There was a disconnect between what I saw on the ground and what I was being taught in the classroom,” she said during a recent interview, emails flickering on a laptop in front of her. “It was great to learn about Frank Gehry but it had nothing to do with the issues facing us on the West Bank.”

The lessons on Frank Gehry were in early 2000, just before the breakout of the Second Intifada and the collapse of the Oslo peace process. As violence engulfed Israel and Palestine, a state of direct military occupation, in which Israeli tanks were stationed in various Palestinians cities, became a daily reality. Ramallah had transformed into a war zone. The aftermath of this violence left a strange status quo in Israel and Palestine. Israeli settlement activity surged throughout the West Bank while leaders bemoaned the need to rekindle the peace process, something that continues until today.

This was a moment in time when the international architectural community was turning its focus to the twin challenges of climate change and a changing global economy. In Ramallah, Masad began to formulate ideas about how Palestine could respond to its own environmental and economic conundrums. How could Palestine house a growing population in ever more limited space when access to both foreign resources and capital were also limited?

The designer started to think about things like building more affordable housing with fewer imported materials and reclaiming waste as raw material for construction. In 2010, she enrolled in a traditional permaculture course in the West Bank village of Marda, near Salfit. The course proved to be a turning point in her career, introducing her to a handful of other architectural alumni from Birzeit University who were motivated to bring green thinking to Palestine. For these young designers, a more sustainable Palestine would be a political statement of independence and a solution to Palestine’s burgeoning housing crisis.

Within a couple of weeks, Masad and three other designers, Ghaith Nassar, Rami Kasbari and Lina Sale, had created Palestine’s first green design firm. The collective is called ShamsArd, which means “sun” and “earth” in Arabic.

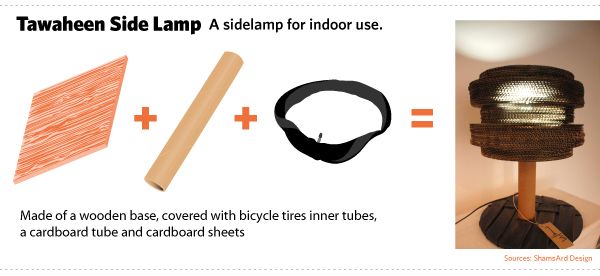

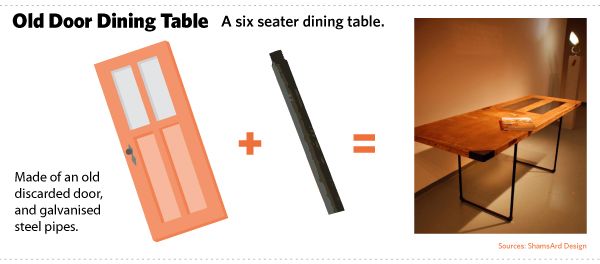

In a small studio buried in the midst of Ramallah’s jumbled architecture, the young firm began building furniture out of trash found on the West Bank. The act had an implicit political meaning — Israel has tight restrictions on shipments and production of anything that Palestinians could use for military purposes, which includes building materials, including cement, gravel and lumber. By reusing materials, the collective demonstrated independence from these restrictions. Inside their studio, old doors become tables and wooden crates transform into a desk suitable for a functioning office. The collective’s latest project is a series of houses in the Jordan Valley made entirely out of earth and mud.

“We are part of an industry that is not sustainable here on the ground,” Masad said. “It is damaging to the environment and also to the community because it is uses materials that are not locally made… This is the part where we believe we can change the local community through empowerment.”

Palestine is a culture steeped in tradition. For that reason, the designers were a bit surprised when their work began to receive positive attention on the West Bank and in Diaspora communities abroad. Their first exhibition of furniture in 2012 nearly sold out. They could hardly keep up with orders coming in. During Palestine’s largest annual art event, the Qalandia International Art and Design Festival, ShamsArd was asked to make a series of public furniture installations throughout the city. Today, some park benches in Ramallah are actually ShamsArd creations made entirely of old doors and other reused construction materials.

Yet changing the minds of local craftsman accustomed to working with new materials has proven to be the most difficult part of the creation process. “We are trying to change the way that people think of their surroundings starting with furniture and building,” designer Rami Kasbari said over a cup of coffee in Jericho. He had just given a tour of their latest earth architecture project in the Jordan Valley.

The project is a private house on the dusty outskirts of Jericho, one of the world’s oldest cities. Rami pointed out the ruins. “People ask us all the time if structures made out of mud and earth can really last,” he exclaimed. “Look, these structures are more than 5,000 years old and they are still here.”

Their buildings are done in a style made famous by Nadar Khalili, a late Iranian-American architect best known for starting the California Institute of Earth Art and Architecture. While materials for the housing project — little more than earth and mud— are cheap, labor is costly and intensive. This is exactly where the issue of independence comes into play. “We would rather provide jobs to Palestinians than use cheaper materials which have to be imported over Israel-controlled borders,” Masad said under a beating desert sun.

[infobox]Masad and her peers are embracing sustainable urban design with the notion that breaking out of never-ending fighting and occupation may require building a better way forward.[/infobox]Ramallah is a small town where it’s hard to avoid running into the same people over and over again. Within this tight-knit population is an increasingly large number of Palestinians who have returned home after receiving education in the U.S., Canada or Europe, bringing with them new perspectives and ideas about the embattled nation’s future. The members of ShamsArd represent this trend. Yet for all their activism and esoteric ideas on design, they remain tied to local culture. In between comments on earth architecture, architect Rami Kasbari mentions his upcoming wedding and the difficulty of remaining traditional in a modernizing environment.

In November of last year, Masbari and other 80 other people — academics, designers, urbanists and artists — gathered on the top floor of a modest five-story building in the upmarket Maysoun neighborhood of Ramallah. They were there for a conference entitled “Modernity, Architecture and Urban Life in the Arab Region.”

Outside of a crammed room, conference co-organizer Nora Akawi, 27, explained why she had decided to put the event together. Looking out over Ramallah and the Israeli settlement of Psagot, which towers above the city like a fortress, the Columbia University-educated curator and architect spoke about the need for more connections between cities in the region, so that the conversation moves beyond the frame of identity and into something more global. These cities can be a “fantastic laboratory for various experiments that go beyond the identity-based narrative that is religious or national, but are political in the sense of action and pluralism,” Akawi said. “Jerusalem specifically can provide a fantastic laboratory for this kind of urbanity.”

Akawi, dressed in the international architect’s uniform of bold eyeglasses and a crisp blazer, is a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship. She was born in the Israeli city of Haifa two years before the outbreak of the First Intifada. After earning a bachelor’s degree in architecture at Israel’s prestigious Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, she moved to New York for graduate studies at Columbia’s School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. She now runs a small design studio, workshop and gallery space affiliated with Columbia in Amman, Jordan. Previously, she helped run Al Ma’mal LAB, a small design studio in Jerusalem’s Old City.

“One of the challenges,” Akawi said, “is that we don’t have the ability to visualize the West Bank and Jerusalem without the divisions that already exist. I think that we need to, as planners, be able to reimagine [the built environment] and free ourselves from the geopolitical divisions that currently consume our land.”

GRAY ZONES

The 10th-century Arab traveler and scribe Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Al-maqdisi once described Jerusalem as “a golden goblet full of scorpions.” Eleven centuries later, Jerusalem remains the beating heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and a primary place of interest for Palestinian urban planners.

Along the road connecting Jerusalem and Ramallah sits the shabby village of Kufr Aqab. It feels lawless: There are no traffic lights, no crosswalks and a near-constant display of garbage clogging the streets. The village is buttressed on its eastern flank by the Israeli separation barrier, a 12-foot-high concrete wall complete with imposing guard towers. Kufr Aqab looks like a forlorn West Bank village, but it is not. The village became part of Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War, in which the Jewish state took control over the eastern part of Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza. Currently, Kufr Aqab exists in the impossible position of being on the West Bank side of the barrier, but still within the boundaries of the Jerusalem municipality. Residents pay city taxes and get little in return. Garbage is collected once every two weeks, water access is infrequent and the Jerusalem police rarely enter.

Kufr Aqab is not the Jerusalem promised by Mayor Nir Barkat in his sleek rebranding campaign for the contested holy city. The neighborhood does not have working garbage disposal system or sidewalks. Driving through, classic stereotypes of maniac Middle Eastern drivers seem apt as one is forced to carefully negotiate potholed streets with no working traffic lights. Without regular trash pickup from the city government, residents resort to burning garbage. As a consequence, dull, thick smoke covers everything with a toxic film. The area is a literal gray zone within the occupation’s strained geography.

Despite its noxious environment, Kufr Aqab is booming. Rents have reached highs unthinkable a few years ago. Developers are swooping into build narrow concrete apartment buildings in alleyways. Bordered by the separation wall and the United Nations-administered refugee camp of Qalandia, Kufr Aqab is unable to expand outward and thus expands upward. Tall apartment buildings can’t be built fast enough to satisfy the demand.

Part of the reason is intermarriage. Love knows few boundaries and neighborhoods like Kufr Aqab, inside Jerusalem but on the West Bank side of the separation barrier, are ideal places for mixed couples to settle.

In a situation of total confinement and virtually zero public resources, the community has stepped in to take control over its neighborhood. Community members patrol their streets at night and handle the episodic crime though a traditional vigilante system.

Enter former Israeli soldier Micha Kurz and Grassroots Jerusalem, a non-profit organization that stepped in to fill the void left by a dysfunctional municipality. After returning from a stint of post-army international travel, Kurz became active in various political movements critical of Israel’s occupation. Born and raised in Jerusalem, he decided to focus his energy close to home. He started his non-profit to provide needs-based assessments of places like Kufr Aqab, neighborhoods long forgotten by the municipality. Arming locals with cellphones connected to an elaborate database, Grassroots Jerusalem has been quietly collecting accurate data concerning the needs of Jerusalemites. In effect, it does the job that the city won’t in Palestinian neighborhoods.

“Israel might take care of issues like water, waste management and maybe even build some new schools in the near term,” Kurz, 31, explains over the din of a bustling West Jerusalem cafe. “But they will do with this without working according to community-based plans. In a sense, the city will do this without any Palestinian leadership within the development.”

“The plan is completely top-down in the sense that Palestinians don’t even have access to the plans,” Kurz adds. “They will watch it happen outside their door. Keep in mind that many Palestinians have not voted for this government and basically have no say whatsoever. They can’t even read the plans because they are in Hebrew.”

Kurz’s long-term vision is to build an infrastructure for civic involvement that incorporates Palestinians into the process. As a former soldier, he isn’t naïve about the unlikely prospect of tearing down the concrete separation walls that cut off Kufr Aqab. Instead, he is focused on piercing the cultural and structural divide that leaves the neighborhood in ugly limbo.

“We are not going to end the occupation,” he said. “But we can encourage the Palestinian population of Jerusalem to become more active in how the city is running, whether through needs-based assessments of neighborhoods or simple translation help. The goal is greater participation in how the city is run.”

It’s a goal that rolls off the tongue easy enough, but what does Palestinian participation in East Jerusalem look like in practice?

Jerusalem City Councilwoman Laura Wharton of the left-leaning Meretz party supports Kurz’s work, but is skeptical about the results it will yield.

“On the one hand, [Palestinians] complain that they are not getting services. On the other hand, there are a lot of people, a large enough percentage of residents that don’t want Israel to take responsibility,” Wharton said over coffee at an Italian café near Jerusalem’s hulking stone city hall. She tells a story to illustrate her doubts: An Israeli friend was involved in a road-paving project Silwan, a Palestinian neighborhood in Jerusalem. The paving was something that residents wanted, but the mostly Palestinian surveyors were afraid to go Silwan because they didn’t want to be identified with the Israeli government. “The ones who did go there were all threatened and attacked, and they had a very difficult time even paving this road,” Wharton said. “On the one hand, they knew that they needed it, but they didn’t want Israel to be the one doing it.”

Since our interview, Grassroots Jerusalem has changed its name to Grassroots Al Quds, adapting the Arabic name for the city in a move that underlines their frustration with continued neglect on the part of Israel. Kurz himself has become an active member of the global Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign in effort to bring a non-violent end to Israeli control in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

A NEW WAY FORWARD

The road to Rawabi, Palestine’s first planned city, is similar to the entrance of an exclusive Southern Californian suburb. Carefully placed olive trees and rustic stones accent the smooth pavement leading to the billion-dollar real estate project. But Rawabi’s precarious location in the heart of the West Bank is impossible to conceal. Scars of Israel’s 44-year occupation litter the otherwise serene landscape surrounding the project. The 20-minute drive north from Ramallah to the new city is dotted with empty Israeli military checkpoints, eerie memorials of the bitter fighting of the Second Intifada. Rawabi’s modest entrance is marked by a series of discreet signs, small enough that passing Israeli settlers can ignore the project’s existence altogether.

Inside the construction site, hundreds of workers and city planners, each wearing neon safety vests and helmets emblazoned with Rawabi’s cheerful logo, are busy building a new kind of city for Palestine. Rawabi, which means “hills” in Arabic, will contain more than 5,000 residential units spread across 23 suburban-style neighborhoods connected by shopping centers, office buildings, parks and playgrounds. On clear days, the Mediterranean coast and the skyline of Tel Aviv glimmer in the distance along with the Israeli settlement of Atara, perched on an adjacent hilltop. The architecture of the project is decidedly Middle Eastern, but not in a Palestinian way. The virtual models, which are handsomely displayed on iPads in Rawabi’s sales office, show a project that looks more like it belongs in Dubai or possibly the outskirts of Tel Aviv, not the placid rolling hills of Palestine. For a society steeped in conservative values, Rawabi’s promise of a modern, stable and safe planned city, where young families can live, grow and work, is a 180-degree turn from what most Palestinians have come to expect in an urban environment.

With roughly $750 million in funding from private Qatari companies, the project enjoys the backing of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. For these leaders, the nation’s largest-ever building project has become a political vehicle carrying the message that Palestinians are ready for their own independent state.

If Palestinians can build its own middle-class city in the midst of the occupation, the argument goes, they can build a state. Given all this, Rawabi has become an integral part of whistle stop tours for international journalists, pundits and policymakers visiting Israel and Palestine.

Inside Palestinian civil society, the project has generated controversy. Late last year, Rawabi launched a large billboard campaign throughout the West Bank with eye-catching projections of the new city throughout. In short order, the billboard in downtown Ramallah was quickly defaced. It now carries the graffiti, “where the Palestinian cause goes to die,” across the bottom of it. Today, most independent political activists see Rawabi as a display of a corrupt mainstream establishment’s power and reach.

“I don’t think that Rawabi is good for Palestine,” said Sahar Qawasmi, an architect working for Riwaq, a Ramallah-based non-profit that documents and preserves historic Palestinian buildings and cities. “It is destroying the urban and cultural landscape of the West Bank for the shallow goals of a narrow group of political and business elites in Palestine.”

However popular or unpopular the project ends up being, its success will have a sure bearing on the future of the region. If it does well, there is likelihood that other foreign investors, especially in the Gulf States, would begin eyeing Palestine differently, pumping money into the local economy, generating jobs and lessening dependency on Israel. Outside the region, the development has already come to symbolise an upwardly mobile, educated and westernised population eager to be done with war and occupation.

[infobox]If Palestinians can build its own middle-class city in the midst of the occupation, the argument goes, they can build a state.[/infobox]Rawabi “touches upon all of the core issues of control and sovereignty,” Robert Danin, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told The Atlantic in February. “This could be a huge, iconic victory for the whole strategy of building Palestine from the bottom up rather than trying to build it at the negotiating table.”

Danin could be talking about Masad and ShamsArd, who are also certainly also dedicated to building Palestine from the “bottom up.” Indeed, however different these two approaches are, both indicate an eagerness to move past the political roadblocks that have stopped growth for years, and a willingness to use development as a tool to do that.

Back at Rawabi, the developers are well aware of the project’s political implications.

“If the political environment improves then you will see Rawabi two and three,” Amir Dajani, the deputy director of Rawabi, said on a recent tour. “If the political environment deteriorates and it is in a state of limbo, then we may have to reconsider our plans and maybe slow down part of the construction.”

He added, “We are living for today’s politics.”

This feature originally appeared in Next City.