Millennial children have better respiratory health than did those in the smoggy ’90s.

Here’s some obvious but nonetheless cheering news from Southern California: Raising children in a place that’s not awash with foul smog, it seems, is actually good for their long-term health.

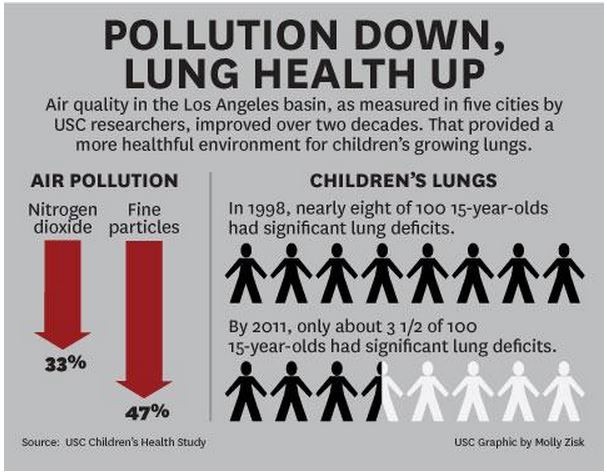

That’s according to researchers at the University of Southern California who spent 20 years following school kids in the L.A. Basin. They say children they monitored from 2007 to 2011—specifically those aged 11 to 15—have much better lung development than a similarly aged group did in the 1990s. And this physiological improvement corresponded with a period of better air quality, they write in the New England Journal of Medicine.

These are some of the ways in which millennial kids are breathing easier than their ’90s-era counterparts, according to the research:

From our partners:

• Their lungs grew 10 percent faster. This quickened development correlates with diminished levels of small particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide (40 percent lower than levels in the ’90s).

• Eight percent of study subjects showed impaired lung function in the mid-90s and 6 percent did a few years later. That number dropped to under 4 percent for mid-2000s kids, suggesting a gradual improvement in public health.

• Race, education level, and even exposure to tobacco smoke didn’t get in the way of their better respiratory health. “These [improvements] were observed in boys and girls, Hispanic white and non-Hispanic white children, and children with asthma and children without asthma, which suggests that all children have the potential to benefit from improvements in air quality,” states the study.

Despite this heartening bulletin, now is not the time to declare victory over SoCal’s floating toxic soup. The lower levels of pollution from 2007 to 2011 were partly due to decreased economic activity during the Great Recession, say the researchers. And with activity on the roads and at the region’s gargantuan ports expected to increase in coming years, there could be another surge in toxic emissions.

And that would be a kick in the diaphragm for people who came of age in the ’90s, whose lungs might be permanently impaired. Says lead author W. James Gauderman in a press release:

“Reduced lung function in adulthood has been strongly associated with increased risks of respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and premature death,” said Gauderman.

“Improved air quality over the past 20 years has helped reduce the gap in lung health for kids inside, versus outside, the L.A. basin.”

The growing years are critical for lung development. The researchers are monitoring lung function in a group of adults who participated in the study as adolescents. So far they have not found evidence of a rebound after the teenage years.

“Their lungs may have lost the opportunity to grow any more,” Gauderman suggested.

This feature originally appeared in CityLab.