The Imperial War Museum has been a poignant and moving memorial to Great Britain’s involvement in modern conflict for nearly a hundred years. In 1917, the British War Cabinet voted to create a national war museum that would record the horrific events still taking place in Flanders. The intention was to collect and preserve artifacts that would tell the story of the First World War, and Britain and her Empire’s role in it.

In 1936, the collection was moved to the former home of the Bethlem Royal Hospital in Lambeth, South London. Better known as the infamous Bedlam, the suitably foreboding and austere Victorian building was one of the world’s most notorious asylums and homes for the criminally insane.

With the outbreak of World War II, the museum’s remit was extended to include all current wars; the museum’s collection today includes the recent Gulf conflicts. The museum itself was hit by over 40 German incendiary bombs during the Blitz, but the museum survived and has grown to become one of London’s most fascinating collections.

The front lawn of the imposing former Victorian asylum is dominated by a pair of giant 15-inch guns from the Royal Navy’s HMS Ramillies and HMS Resolution, aimed in the direction of the River Thames. The main atrium is just as over-awing; suspended from the ceiling are an RAF Supermarine Spitfire that saw action in the Battle of Britain, as well as actual V1 and V2 rockets that terrorized London during the Blitz, and a Reuters news agency Land Rover that was hit by a rocket in Gaza in 2006.

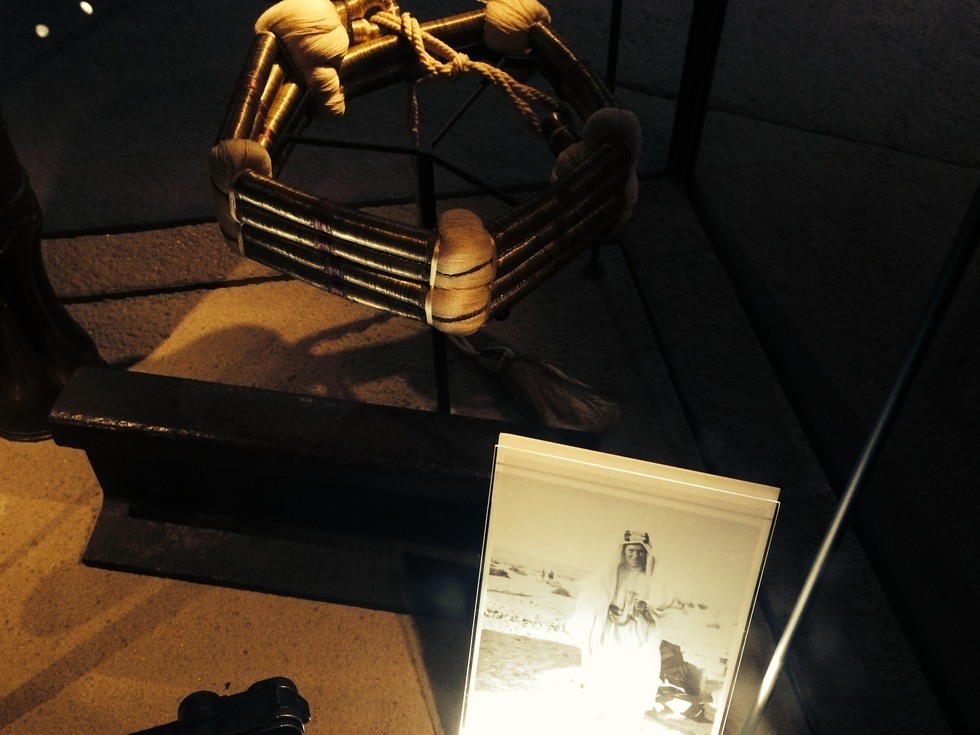

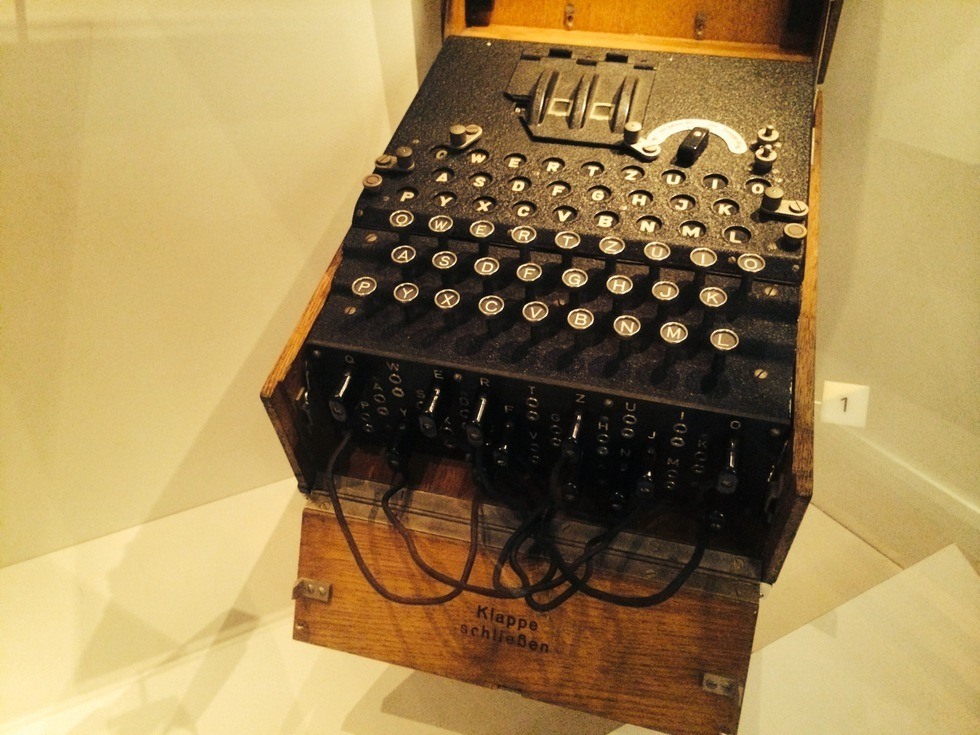

The scope of the museum runs to over 10,000,000 artifacts, including such extraordinary items as the original bronze eagle that crowned the Reichs Chancellery in Berlin, Captain T.E. Lawrence’s own personal Arab headdress, and one of the few surviving German “Enigma” code machines.

From our partners:

But it is the original First World War exhibit that continues to be the most affecting. Benefitting from a recent £40 million refurbishment to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the start of the Great War, most of the entire ground floor of the old hospital is given over to the “war to end all wars.” Gas masks, bullet-ridden signposts from the British front lines named for familiar home streets such as Tattenham Corner and Picadilly Circus, and barbaric-looking homemade trench clubs all speak to the horrors of the Western front that millions of men lived such desperate lives in.

Two artifacts on display are perhaps the most moving of all. The first is a torn sheet from a British army signal pad. Hand written in pencil and headlined “VERY SECRET,” it reads, “Zero hour will be at 3:50am tomorrow, 31st July.” Delivered to a front line commander, it was the dreaded order to go “over the top,” and began the Third Battle of Ypres, known as Passchendale. It was one of the most infamous battles of the war, known for the colossal number of casualties, and the heaviest rain storms seen in Flanders for 30 years, which turned the trenches into a nightmarish landscape of craters in which many soldiers drowned in the clogging mud. The hastily written signal ordered hundreds of thousands of men to their deaths in the shattered landscape of mud, treacherous shell craters, and barbed wire.

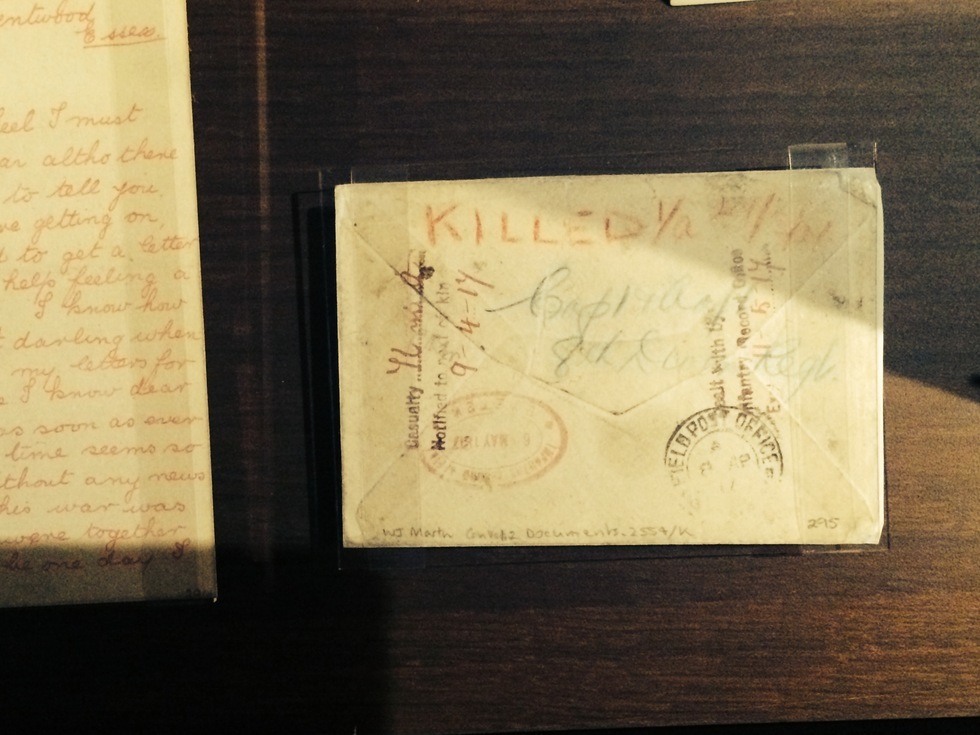

The item next to it is a letter written from an Emily Chitticks to her fiancee William Martin at the front: “My Dearest Will, I wonder how you are getting on. I shall be so relieved to get a letter from you. I can’t help feeling a bit anxious dear…..time seems so dull and weary without any news of you, if only this war was over dear and we were together again. It will be one day I suppose.” Unbeknownst to her, it was written the day after he was shot by a German sniper. The letter was returned to her with one word scribbled in red pencil on the envelope: KILLED.

Letters to soldiers in the trenches were the only form of communication and were essential to morale. Emily’s letter would have been delivered in one of the 19,000 mail bags that crossed over the English channel each day in 1917. The Imperial War Museum has curated over 7,000 of these heartbreaking letters to loved ones. Emily died in 1974 having never married.

The letter poignantly highlights the far-reaching consequences of the simple battle order marked “Very Secret.” The Battle of Passchendale ended just over three months later at a cost of over half a million casualties, with little gains to show.

A trip to the Imperial War Museum is a sobering reflection on the horrific events that took place a hundred years ago. Harry Patch was the last British veteran of the Western Front to die, passing away in 2009. He is quoted in the First World War Gallery: “I’ve tried for 80 years to forget it. But I can’t.”

This feature originally appeared in Atlas Obscura.