The centerpiece of New York’s New Fulton Center, the Sky-Reflector Net recalls an era when transit design aspired to great beauty.

Fulton Center, the massive new subway station unveiled by the New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority [November 2014], is by far the city’s brightest transit hub. The $1.4 billion upgraded and redesigned center unites nine subway lines across downtown Manhattan, providing easier transfers, expanded tunnels, all-new digital signage, and better ADA accessibility for some 300,000 riders a day. It also features one thing no other subterranean subway stop in the city can boast: a view of the sky.

The Sky Reflector-Net, an artwork by James Carpenter Design Associates, Grimshaw Architects and engineering firm Arup, transforms the center’s already grandiose atrium into something to marvel at. The cable structure, suspended from a skylight 110 feet above ground level, diffuses and reflects light a full two stories underground, solving a classic problem in subway station design: the dearth of natural light. Despite having the nation’s biggest public transit network, this is a particularly vexing problem in New York City (look no further than the soul-suckingly dingy, dark subterranean labyrinth that is the modern Penn Station.)

Sky Reflector-Net’s cross-hatch pattern, created by aluminum panels hung on the cable net, draws the eye upward into the conical atrium. The sunlight casts a projection of the sky above onto the aluminum panels. Combined with the incline of the 53-foot-diameter oculus itself, angled toward the south, it’s a stunning visual effect, one that turns Fulton Center into something more than a hall you dash through to catch a train. It’s almost a pleasant place to be.

From our partners:

“We try to set up opportunities where people in their day-to-day activities discover something about a particular location that is perhaps both surprising and remarkable,” Carpenter tells Co.Design.

The designer, who helped develop Fast Company’s glassy office tower here in lower Manhattan and has long played with light in his work, was an obvious choice when the MTA’s Arts & Design program sent out a call for artists in 2004 to work with Grimshaw Architects on the Fulton Center pavilion. The architects, appointed to the project in 2003, were already “very captivated by the notion that daylighting could form a really powerful and profound component of the design,” says Vincent Chang, a partner at Grimshaw.

Carpenter’s proposal aligned with ideas about light and creating a grand public space—something on par with the iconic Grand Central Terminal—that the architects had already been discussing. “Our practice is about light in the public realm,” Carpenter says of his studio. “That’s the trajectory of our work: how light becomes an animator of public space.”

Our work is about how light becomes an animator of public space.

The Sky-Reflector Net, made of 952 perforated panels made out of optical aluminum and attached to a structure of 112 tensioned cables, becomes a connection between the subterranean city, with its blocks and blocks of subway connections, and the sky far above. The optical aluminum—which reflects a high percentage of light, but doesn’t create hot-spots of glare—paints a kind of diffuse portrait of the sky inside the building, one designed to resemble the soft, colored sheen of the film on a soap bubble. Carpenter intends it not just connect people to the outdoor world, but to the kind of natural light that in dense cities is often obscured by buildings. He is interested in exploring “the levels of complexity and intricacy and even beauty that exist in light” in a natural environment, he says. “We think of ourselves in an urban environment as being divorced from nature—how do you reconnect people with that sensibility of a richer world that we always associate with being outside of the city?” If you stand there for long enough, you can see the clouds moving.

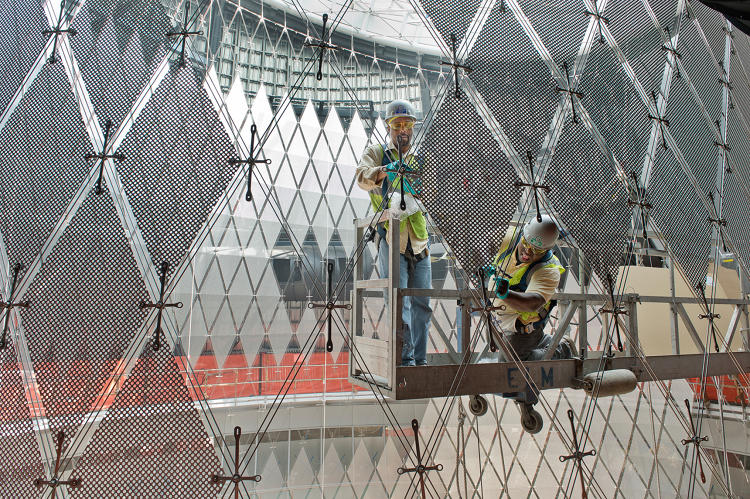

Though the design process lasted for nearly seven years, the actual construction of the Sky Reflector-Net took just six weeks. The 4,000 pounds of cable for the net, prefabricated in Massachusetts, arrived at the site already knit together, “basically rolled up as a carpet,” as Carpenter puts its. Before that, the architects, engineers, and designers involved went through numerous iterations, computational analysis, and what Chang describes as an “exhaustive amount of testing” to ensure that once the net was hoisted into place and its cables tightened, it would have the precise geometry and curvature intended.

The basketball net shape (an “eccentric toroid,” according to JCDA) serves to “increase the apparent loft of the space, to maximize the feeling of connection between the atrium and the concourse and the sky above,” says Nikolas Dando-Haenisch, a principal at Grimshaw. “It’s a bit of forced perspective to enhance the character of the public space.”

And creating a precise, predictable shape was not only about maintaining the net’s aesthetic qualities, but with a practical need for the artwork to integrate into the architecture. The perforated panels perform a duty that goes beyond artistic value: they’re part of the building’s smoke evacuation system. The panels obscure a great deal of building infrastructure, including emergency fan systems and ducts that would serve as the exit point for smoke should a fire ever occur in the subway tunnels below. “It works as a way of concealing a great deal of mechanical equipment,” Carpenter says.

Even during the depths of winter light will reach the bottom of the atrium.

Glass fins at the top of the skylight are oriented to maximize the amount of days during the year daylight will enter the space, so that even during the depths of winter light will reach the bottom of the atrium. “We didn’t want to explicitly make it a sun dial, but it actually could do that if you were really astute,” Carpenter says.

“This idea of bringing in a sky into the building is almost reframing a historical part of architecture,” Carpenter says. “In Grand Central, the ceiling is a painting of the sky. It’s a tradition of architecture,” he explains. “In our version, it is the sky—you’ve brought the image in as a true real-time projection.”

Rarely do trudging subterranean commuters have reason to gaze toward the ceiling lest it’s to avoid something leaking on their heads. Here, at last, there’s a reason to. With it comes relief from the crushing oppression of low-ceilinged underground mazes that only the savviest of travelers emerges from with any sense of direction. If there is any 21st-century model for the kind of grand public transit architecture New York built in the early 1900s, with Grand Central and the original Penn Station, this is it.

This feature adopted from FastCoDesign.