What is life like in Mali’s ‘city in the middle of nowhere’? Guardian photographer Sean Smith recently spent a week there, meeting everyone from Timbuktu’s chief muezzin to its only DJ.

Timbuktu’s clay-built Djinguereber mosque, commissioned in 1327 by emperor Musa I, at the end of Friday’s midday prayers.

An entertainer catches his breath during rehearsals. The city’s annual music festival ran for a decade until 2011, when a visitor was killed and three more were abducted.

From our partners:

The entrance to Timbuktu, a city largely run on donkey power whose population is now thought to have dropped below 15,000 people.

The 76-year-old muezzin of Djinguereber mosque, Mahamane Mahanmoudou, after making his early morning call to prayer.

The leader of the butchers’ corporation Mahamane Traore, 68, at the open-air slaughterhouse just outside the city limits.

Reaching the river Niger from Timbuktu requires a 30-minute drive along 12 miles of potholed road. Here, World Food Programme sacks are loaded on to boats to be shipped along the river.

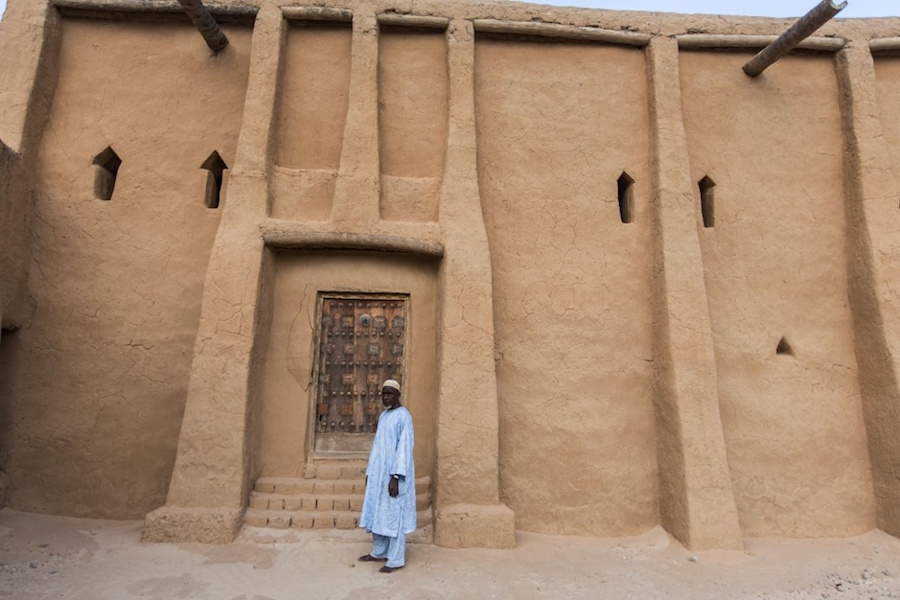

The muezzin of Djinguereber stands by the first of a series of doors into the mosque. Locals say if they are all destroyed, the world will end.

United Nations police on a foot patrol through the city. When France intervened militarily in January 2013, the UN followed with 10,000 soldiers and police.

Timbuktu’s open-air slaughterhouse. A new abbatoir was built but was seen as too far from the market, then was looted when rebel occupiers withdrew from the city.

The mosques and old buildings in Timbuktu are made from ‘banco’ – sand collected on the city’s outskirts and mixed with water. The technique is listed by Unesco in a special World Heritage category.

A rudimentary customs stop on the road into town. Timbuktu is a staging post on the desert trafficking route for both drugs and people.

Haoussa Tandina, 35, is the main breadwinner in her family. Her many businesses include making ice and juices, and selling fabric and clothes.

Volunteers clear rubbish close to the Djinguereber mosque. Much of the city’s waste gets dumped in the desert.

A DJ performs a sound check in the only nightclub in Timbuktu.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

A young boy collects water from one of the few remaining waterholes on the outskirts of the city.

A man takes a break from digging for banco. This free material has excellent insulation qualities, but requires a lot of maintenance.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

With midday temperatures in the 40s throughout summer, locals often stay out on the streets socialising until midnight.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

The hotel purchased by the late Colonel Gaddafi a decade ago; the former Libyan leader dug out the Timbuktu canal all the way to the Niger river in 2006.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

A demonstration at the city hall by civil defence force members, protesting at their exclusion from talks in Algeria aimed at brokering a settlement between warring Malian groups.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

Awaiting the catch at the fish market in the small village of Toya, on the banks of the river Niger.

The city’s local historian, Salem Ould Elhadje, says life in Timbuktu ‘is like the years of segregation in the United States’.

Diadié Hammadoun Maiga, 67, on the roof of his home. Maiga stayed put in 2012 to head the city’s crisis committee during the jihadist occupation.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

People, goods and livestock are crammed on to the back of an old truck and taken to Timbuktu from the river Niger.

Children wearing cattle horns play a version of ‘trick or treat’ during the first phase of Ramadan.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

Two boys walk past the Djinguereber mosque. Its annual restoration requires a team of 20 builders.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

UN police observe one of the city’s many donkey-pulled traps – Timbuku’s equivalent of the ‘man with a van’.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

The headmaster of Timbuktu’s Qur’an school, Abdoul Wahab Haidara, writes passages of the holy book out on wooden tablets for students to recite.

A UN armoured vehicle returns to the city limits after a patrol to the Niger river at Korioumé. There has been a recent surge in attacks on UN peacekeepers in northern Mali.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

A young boy sporting a Cristiano Ronaldo football shirt and large knife follows a limb of raw meat as it is carried from open-air abattoir to market.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

Dancers and singers during rehearsals. The Timbuktu Renaissance Initiative seeks to restore the city as ‘a beacon of tolerance, wisdom and innovation – the signature characteristics of its golden age’.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

Protesters demanding their voices be heard at the city hall. According to residents, rebel fighters are still present but dormant in Timbuktu, and active all around it.

For Cities: Timbuktu, Mali, Africa (Photograph : Sean Smith/Guardian)

The Djinguereber mosque during a sandstorm. The Sahara desert is encroaching on Timbuktu’s northern limits, stifling life in the city.

This feature originally appeared in The Guardian.