Long before America’s current urban revival, the Strip was ditching its streetside car parks for promenades and conceiving its own version of the ‘Bilbao effect’.

The Las Vegas Strip isn’t in Las Vegas. You’ve got to understand that before you can understand anything else about this glittering, 4.2-mile stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard described by William L Fox as “the most aggressively branded and promoted concatenation of adult theme parks in the world”. It is also among the most visited places on Earth, having surpassed Mecca back in 1999.

The Strip was created in Paradise, an idyllically named township of Nevada’s Clark County formed by hotel builders who had already built strategically outside city limits as a means of minimising taxes, dodging regulations and avoiding utility disputes with the city proper. Since Paradise’s founding in 1950, the unabashedly capitalistic and hedonistic Strip has seen an astonishing buildup, especially during its two most notable boom times: the mob-run 1960s and the corporatised 1990s.

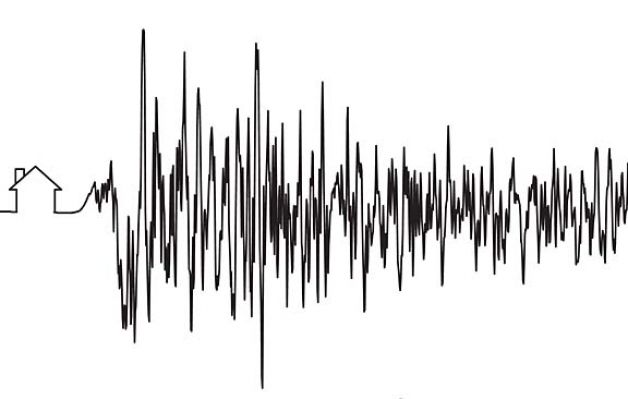

But what kind of an urban experience has resulted? To a first-time visitor, the Strip can look and feel like the concretisation of unplanned chaos – with its waves of pulsing lights and scrolling video screens; its “riot” of clashing, garish architectural styles; the wide central river of frequently gridlocked traffic; and the swarms of tourists, all dressed with aggressive casualness and milling blindly every which way. But does it make any sense at all to apply the term “urban planning” to the Strip? Or is this simply what happens when money dictates every aspect of a built environment?

“It seems to me that urban planning has had nothing to do with the Strip,” says Michael Green, associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and co-author of Las Vegas: A Centennial History. “For the most part, builders have been free to build as they please.”

From our partners:

In the early 1930s, says Green, “the building of the Hoover Dam and the nascent tourism industry turned Las Vegas into a city dependent on federal projects and visitors. Economic diversification always has been limited, so the attitude too often has been that if someone wants to build, unless it’s a real problem, let ’er rip!”

And rip it has. The dominance of this laissez-faire approach to architecture and urbanism produced, over the following decades, a flamboyant, unapologetic, gambling- and entertainment-driven pseudo-city that observers found compelling and repulsive in equal measure.

The repulsion eventually fuelled a great aesthetic controversy in 1972, when the architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour published Learning from Las Vegas, which dared to approach the built environment of the Strip on its own terms.

“Las Vegas is to the Strip what Rome is to the Piazza,” the trio declared, having a grand old time enumerating the freakish architectural mini-movements that had emerged there, from “Miami Moroccan, International Jet Set Style” to “Yamasaki Bernini cum Roman Orgiastic” to “Bauhaus Hawaiian”. But they also noted that, while the Strip originally “just grew”, they were seeing the emergence of “the usual building and zoning controls” and even a “Strip Beautification Committee”. It gets them worrying: “What will happen to the Strip when the tastemakers take over?”

More than four decades on, however, anyone setting foot on the Strip will soon realise – with relief or horror – that nobody remotely describable as a “tastemaker” has yet taken over. The place has, if anything, gone much further over the top, presenting visitors with streetside spectacles unthinkable in the era that Venturi, Brown, and Izenour were writing about: elaborate fountain shows at the Bellagio electronically choreographed to pop hits; canals dug into The Venetian hotel, complete with stripe-shirted gondoliers; a 541-foot replica of the Eiffel tower at a casino-hotel called, simply, Paris.

“There is a difference between the planning of the Strip versus other parts of the Las Vegas Valley,” Mario Bermudez, Clark County’s zoning planning manager, tells me. “On the Strip, we routinely review multimillion to multibillion dollar projects. Because of the tax and gaming revenue generated from these projects, the entire State of Nevada benefits. While other projects throughout the Valley do provide an economic benefit to the state and county, it is not at the same level as the Strip properties.

Bermudez highlights the need for close cooperation with private companies in order to address the challenge of “how to adequately provide services to such a concentrated area … The Strip is only four miles long, and the number of pedestrians and cars requires us to work very closely with the resort hotels and other businesses to provide for the adequate movement of people and cars. We negotiate development agreements to mitigate impacts such as traffic, water sewer and public safety.”

More local-government mechanisms have indeed engaged in recent decades – but mostly to facilitate the Strip’s demolition, rebuilding and upward expansion. “To streamline and speed up the permitting process for the Strip, Clark County set up a special team of planners: the High-Impact Projects team,” says Stefan Al, associate professor of urban design at the University of Pennsylvania and author of a forthcoming book on the Strip. “They negotiate with corporations on a development agreement for each project” which dictates that the developer must include or fund certain pieces of public infrastructure.

Still, much remains as it ever was in this arrangement of, as Hal Rothman put it in his history of Las Vegas, Neon Metropolis, “little city-states, interrelated little kingdoms, entirely self-contained and at war for customers”. Enter any one of them, and you still contend with what Learning from Las Vegas calls the “intricate maze” that “disorients the occupant in space and time. One loses track of where one is and when it is. Time is limitless, because the light of noon and midnight are exactly the same. Space is limitless, because the artificial light obscures rather than defines its boundaries.”

But perhaps the most noticeable difference between today’s Strip and the one from which Venturi, Brown, and Izenour learned is in its relationship with cars. In the early 70s, they described casinos surrounded not by literal lakes, full of fountains and gondolas and what have you, but by lakes of parking.

“In the old Las Vegas, nobody walked anywhere,” writes Rothman, whereas by the 21st century, the Strip had become a promenade: “A de facto one created not by planners but by the feet of thousands. Every day, tens of thousands stroll the Strip and drink in the spectacle.”

Not only did this transformation occur in the 1990s, before America’s current urban revival got into full swing (with its associated trend for greater pedestrianisation), but it occurred in a context where, according to Al, “gaming industry interests easily prevail in a context of unincorporation, fragmented government, a limited tax base, powerful gaming lobbies and the absence of a city hall. So what is fascinating about the Strip is how, in spite of these looser planning conditions, corporations became interested in implementing good planning and urban design principles.”

Of course, the builders of the Strip have long understood the appeal of traditional cities, or at least simulacra thereof. In addition to those replicas of Venice and Paris, visitors can also eat, drink, and gamble in spaces themed after mid-century New York and ancient Rome (resorts modelled on London and San Francisco also reached the planning stages in the early 2000s, before the economy soured). But no project more overtly articulates the Strip’s response to the comeback of the American city than MGM’s CityCenter, which opened in 2009 at a cost of nearly $10bn, the most expensive private development in the country.

Al describes CityCenter as the product of “the Bilbao effect: the notion that buildings designed by celebrity architects bring in tourists, and in particular a higher-end type of visitor”. MGM’s version was to bring in name-brand architects such as Daniel Libeskind, Helmut Jahn and Norman Foster, and to install public art by the likes of Maya Lin and Claes Oldenburg. Furthermore, CityCenter is a mixed-use complex, including about 2,400 residential units. “It goes against the casino design convention,” Al says, “by having towers that let in natural light and meet the street the way buildings do in other cities” – with retail spaces, not gaming. This has long made good economic sense; the Strip’s non-gaming revenue began exceeding its gaming revenue back in 1997.

“Superficially, one can claim that the newer hotel-casinos on the Las Vegas strip are more ‘urban’,” says Aseem Inam, associate professor of urbanism at Parsons The New School for Design who is currently writing a book about CityCenter. But, he warns, “some of these claims come more from the project developers” – as when MGM itself calls the project “one of the world’s largest environmentally sustainable urban communities”, or when the Department of Comprehensive Planning, which oversees and approves projects on the Las Vegas Strip, promotes it “as an example of cutting-edge urbanism”.

“A closer look reveals it to be otherwise,” says Inam, citing the expense and absentee ownership of CityCenter’s condominiums, the confinement of its “so-called ‘public’ spaces” within private property, often with restricted access, and – contrary to the project’s claims of pedestrian-friendliness – “a prevalence of automobile-friendly features”, including four large parking garages and its main entrance, a “whopping” eight-lane “driveway” which pedestrians can’t cross, having instead to use a series of escalators and bridges. “While cars flow in and out of the property smoothly, pedestrians are made to do this dance, primarily to entice them into the shopping mall, restaurants, casino and hotel.”

And while CityCenter incorporates certain elements of “real” cities, the project seems wholly to have forgotten about others. Green recalls once being interviewed by MGM representatives about his take on CityCenter’s “mixed-use” nature: “I wondered what people were going to do for groceries and schools, and how traffic would be affected; the interviewers seemed shocked at the very idea.”

For all its vices, CityCenter does have virtues: the architecture itself (though Foster’s hastily built Harmon Hotel will be demolished before ever having opened); its six gold certifications from the US Green Building Council (a degree of environmental friendliness that convinced the Nevada legislature to allow CityCenter an estimated $390m tax break); and, as part of its deal with the High Impact Project team, the inclusion of such public infrastructure as a fire station, contributions to a new police station, and an almost $2m contribution toward a storm water retention basin.

But as always in Las Vegas, the places of greatest interest aren’t in the public realm but the quasi-public private one. Or as Learning from Las Vegas puts it, “the relation between public space, public-private space, and private space is as intricate and intriguing as that of the Rome of the counter-reformation.” Though now considered an urbanist no-no due to their tendency to drain activity from the street, the countless elevated pedestrian bridges across Las Vegas Boulevard stand as an example: though very much private space, they nevertheless give rise to their own social and commercial ecosystems of buskers, beggars and entrepreneurs with coolers full of cold beer.

Developments such as CityCenter have even gone so far as to build their own transportation systems – in its case, a free tram taking riders to the Monte Carlo Resort to the south and the Bellagio to the north. Casino mogul Steve Wynn, more than anyone else the maker of the modern Strip, planned in the 1990s to connect all his properties in this manner, but the formidable Caesars Palace, which stands between Wynn’s Mirage and Bellagio, refused him permission to cross its property.

Al characterises these trams not as proper transit, but as examples of developers employing “weapons of mass traffic” against one another. And while they point to the surprising potential of Las Vegas’s thoroughly private approach to urbanism, they also highlight its predictable limitations. The agonisingly slow bus lines running up and down the Strip will, for the foreseeable future, remain in dire need of a dedicated lane, and without proper public funding, the Las Vegas monorail that entered operation in 2004 has had to defer the dream of connecting the airport, the Strip and downtown.

The corporate consolidation of the gaming industry, has, at this point, put the majority of the buildings on the Strip into the hands of just three corporations. And while this certainly eases the construction of that quasi-public infrastructure, obviating many disputes over tram and overpass pathways, it could also, as Al says, result in a situation where “Las Vegas’s designers would be hindered, just like Disneyland’s, by the demands of a single client, resulting in blandness.”

Despite its endangered flamboyance, however, we can continue to learn from Las Vegas, especially on the question of whether private enterprise alone can produce a functional urban environment. The answers – both yes and no — are illustrated with characteristic vividness on the Strip.

This article originally appeared in The Guardian.