The wind speed in this breeziest of cities once hit 154mph just a few miles from the centre, but it’s not as bad as it sounds – 62 turbines generate the city’s electricity, while air pollution is non-existent as any fumes are whipped away.

On the harbour front in Wellington stands the figure of a man. Naked, eyes closed, he leans forward into a never-ending gale, a look of abandonment – perhaps joyful – moulded onto his cast-iron face.

“Wellington and its elements provided me with a degree of solace in a time of unrest,” says Max Patte, the sculptor behind the self-portrait. “A transitional period of my life following a move from my home in London.”

While it may be metaphorical, the sculpture also captures Patte relenting to the constant breezes of his adopted home. The capital of New Zealand is, by reputation, the windiest city on earth and it can make every day something of a trial.

“I would never say I have learned to ‘love’ Wellington’s most famed element and, at times – most times – I find it to be exhausting,” says Patte. “However, you know you’re home when there’s a southerly blowing.”

From our partners:

Judging which is the world’s windiest city is tricky, as no global database for cities exists and measurement techniques are not standardised. Other contenders include Rio Gallegos and Punta Arenas in Argentina and Chile’s windswept southern Patagonia. St John’s in Canada is north America’s windiest city, averaging between 13 and 15mph.

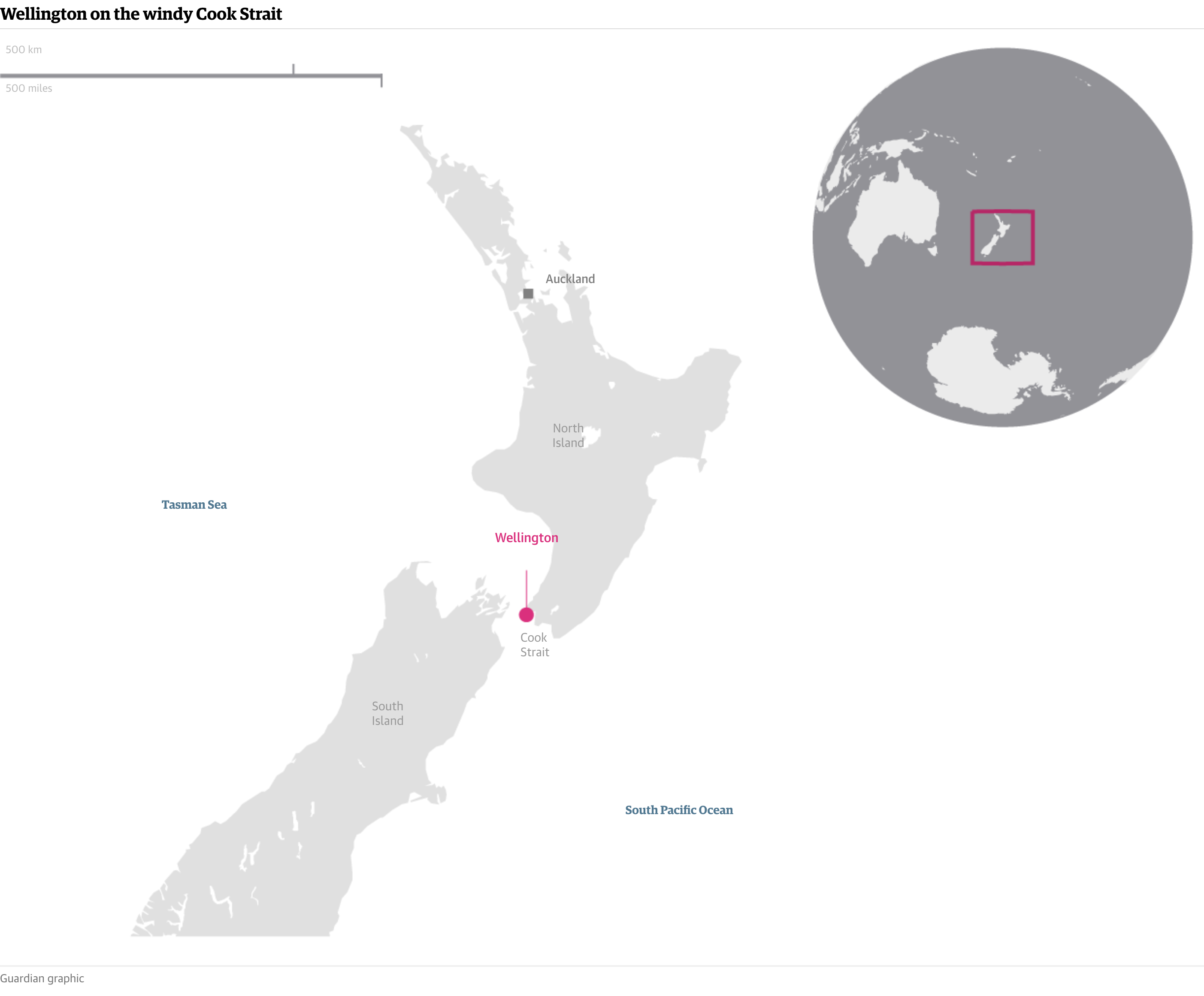

Wellington sits on the Cook Strait, a passage between New Zealand’s north and south islands. The winds of the Roaring Forties, which spin uninterrupted from South America thousands of miles to the west, are funnelled into this 14-mile-wide gap, creating a “river of wind” that rocks the boats in the harbour day and night at an average of 16.6mph. The north island’s strongest recorded gust of 154mph was measured on Hawkins Hill in 1962, just a few kilometres from the city centre.

“There’s no place in the world quite like it,” adds Patte noncommittally.

Sailors, windsurfers and kite-surfers come from afar to ride the vortex. Air pollution is non-existent as any fumes are whipped away and wind power is harnessed for electricity.

“Perhaps the best thing of all, it breeds a bunch of sturdy, resilient Wellingtonians who aren’t fazed by a little bit of wind.”

Wind power is the obvious upside of a breezy climate, and Wellington has 62 turbines set on the hills around the city. Christian Kjaer, the head of knowledge at the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena), says New Zealand is the only country he knows of that has removed all government wind subsidies.

“Onshore wind is doing great because New Zealand has a fantastic wind resource. Wellington is a very good example of how well onshore wind competes with fossil fuels and other sources in free competition where there are no subsidies,” he says.

Windy cities in Europe, including Spain’s Pamplona, Germany’s Hamburg and multiple Danish cities, have successfully harnessed wind to produce a large proportion of their power.

It’s advantageous for cities to be able to generate power close to their centres as it lowers the cost, but cities are challenging landscapes in which to place turbines as buildings can break-up the breeze, affecting the quality of the turbine’s spin.

One place to look, says Kjaer, is out to sea, where the wind is 40-50% stronger. In New York, with its thicket of skyscrapers chopping up the wind, plans are being drawn up for a massive offshore wind farm. In Copenhagen, it’s already happened.

Although wind’s advantages can be great, there are downsides, says Kansas assistant state climatologist Mary Knapp. Her home state is plagued by tornados, and the high-plains town of Dodge City is the windiest city in the US.

(Note: Chicago’s blustery reputation may be less due to the breeze whipping off Lake Michigan and more the relentless windbagging of its 19th century politicians. There is a long running – and vaguely ironic – debate over this factoid.)

In Dodge, the average wind speed is 14mph, but Knapp says this speed is almost a constant.

“What you do notice is when it isn’t windy,” she says. “You may have a brief period in the early morning hours when the sun is rising, or in the late afternoon when the winds die down a little bit. But that would be winds dropping down to two or three miles an hour, instead of 25-30 miles an hour.”

Besieged residents build wind breaks and plant trees around their homes to break up the wind. Homes are built with tiny windows on their northern side to block the savage winter gales. Many are actually dug half into the ground.

Kansas sits on the battlefront where high pressure systems roll down the Rocky Mountains from Alaska and Canada, crashing into low pressure systems that rise from the Gulf of Mexico. The difference in pressure causes air to rush violently between regions. Winds can reach speeds high enough to blow a locomotive off the track, says Knapp. This confluence is also responsible for Kansas’s infamous tornados – although they rarely hit Dodge city.

Again, Kansas has taken advantage of its geography by harnessing the breeze. The most pure iteration of this is the story of Greensburg. After the town was completely destroyed by a tornado in 2007, residents rebuilt the town as a green energy paradise. Its wind now generates three times more power than the town uses.

Wind’s destructive power is most frequently felt in the Philippines, where more typhoons make landfall than anywhere else. The country has 21 of the 100 most exposed cities to natural disaster, according to the Natural Hazards Risk Atlas. Tacloban, which was destroyed by typhoon Haiyan in 2013, doesn’t even make the top five. Tuguegarao (2nd) and Lucena (3rd) both rank higher than Manilla (4th), but the sheer scale of a potential catastrophe in the country’s 12-million-person capital makes it a grave concern.

In Wellington, the gusts will destroy property on occasion, but Patte says the city, like his statue, bears the torment with grace.

“It makes me smile when I read online that the UK is experiencing ‘high winds’. High winds in the UK equate to a gentle breeze down here,” he says. “[But] after all, its the element to which I owe the inspiration for my most-famed work. Thank you, wind.”

This article originally appeared in The Guardian.