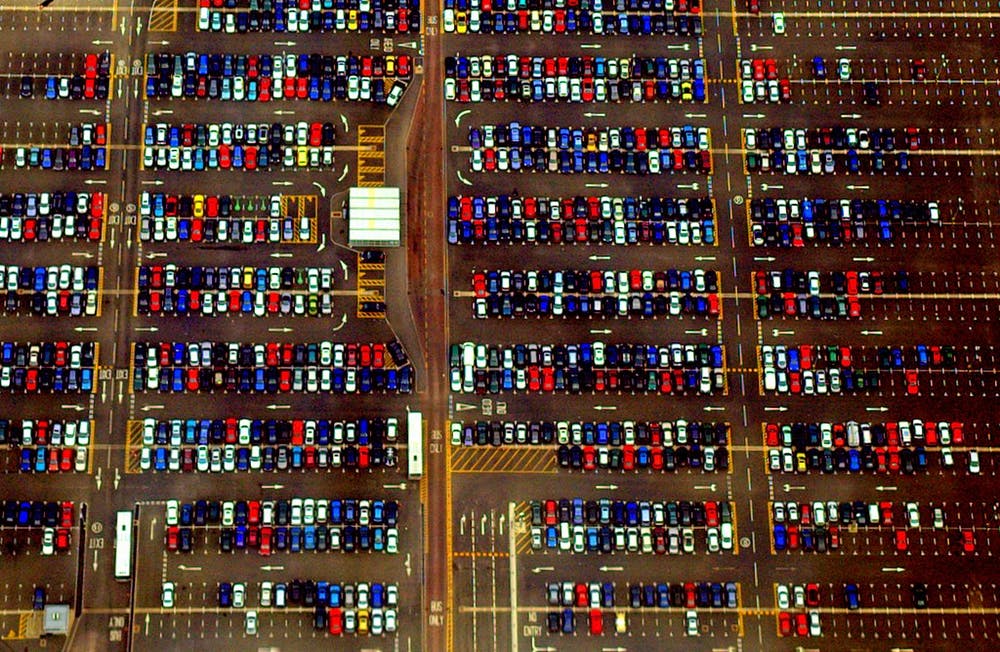

Car parking is expected but often unnoticed, taking up surprisingly large proportions of city space. A parking bay occupies at least 13 square metres – some codes specify up to 30 square metres including accessways.

Website What the Street maps space for different transport modes in cities such as Los Angeles, which has more than 1,000 hectares of surface car parking. Another study found 14% of LA County was set aside for parking.

Yet people nearly always underestimate car space. In Rethinking a Lot, Eran Ben-Joseph found that while the US has at least 800 million parking spaces – almost 2.5 per person – people typically notice parking only when looking for a space:

“We demand convenient parking everywhere we go, and then learn not to see the vast, unsightly spaces that result.”

Obviously, all this parking emerged to cater to rising car ownership throughout the 20th century. And, on average, cars are parked 95% of the time.

From our partners:

But in the US and Australia, very little parking is a market-based response to demand. An estimated 99% of parking in the US is free to the user. In Melbourne, Australia, 95% of parking trips over 2012-14 were free to the user. Unlike food or housing, parking tends to be considered a public infrastructure or right rather than a market good.

One reason for the amount of parking, and our expectation it should be free, is the land use planning system. Many city planning systems set minimum amounts of off-street parking for new developments, with a view to protecting (normally free) on-street parking.

Researcher Paul Barter identifies three types of parking policy: conventional, parking management, and market-based parking (Japan is a rare example of the third type).

Conventional policies treat parking as public infrastructure and aim to predict and provide generous amounts of it. Such approaches became widespread over the 20th century.

A case study: Melbourne

For a 2017 paper I traced the historical development of parking policies in one city, Melbourne.

I identified references to car parking in a review of planning documents from 1929 to 2016, both strategic documents – the broader stated goals for the city – and the statutory instruments that more directly shape urban development.

Melbourne’s first strategic plan was the 1929 Plan for General Development. While never implemented, it gives an insight into how city problems were thought of. Parking was a major concern.

The document discusses pressures from increased car ownership and the:

… increasing desire on the part of the owners to use the curb space … who have come to regard this facility as a moral obligation on the part of the authorities to preserve for them.

Planners were critical of this expectation and proposed a metropolitan parking authority to manage street space. During the subsequent Great Depression and war years, however, strategic plans were not implemented.

By the time of Melbourne’s first implemented strategic plan in 1954, the context was increasingly widespread car ownership. This plan referred to the “formidable problem of finding accommodation for parked cars” in older areas, and called parking “one of the greatest challenges to city administrations the world over”.

The problem of parking was redefined from one of too many stationary cars to a lack of parking space for cars. By 1954 the idea of parking on the street as a public right was, if not considered a good idea in planning strategy, acknowledged as a widespread expectation.

The 1954 plan had two main parking goals. The first was adapting older pre-car areas to the preferences of car drivers. It sought to save pedestrian-oriented areas by integrating parking via demolitions and other means, warning that:

… parking spaces should not only be adequate in number, but … must also be located convenient to the shops because shoppers do not want to carry their purchases a long way to their cars.

Second, the plan sought to build new parts of Melbourne around ample parking. It introduced minimum parking ratios – amounts of off-street parking required of new developments. For example, one parking space was mandated per 20 square feet of public bar in new hotels.

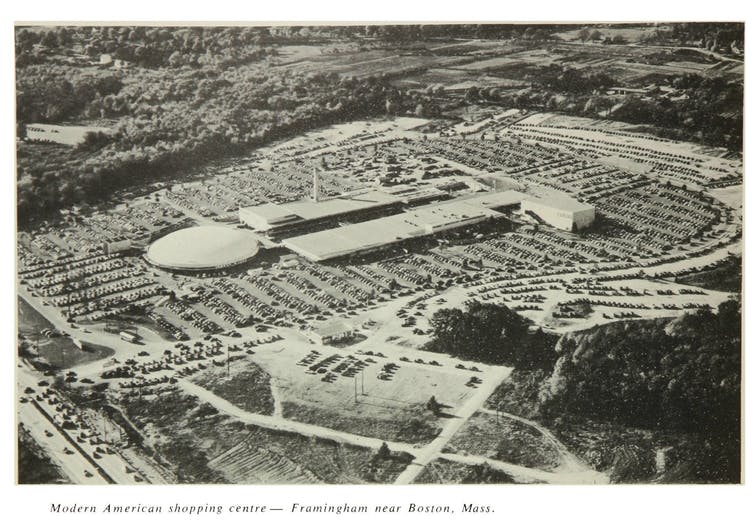

The rates were seemingly inspired by a visit from a Los Angeles planner in 1953 and were openly modelled on US standards. The document showed an “American shopping mall” surrounded by parking and noted that “by contemporary American standards” the new policy requirement “would be inadequate, but it is much in advance of what is available today in Melbourne”.

So, in post-war Melbourne, ample car parking was specifically planned as a key part of building a car-based city.

In later decades, Melbourne strategic planning documents (in 1967 and 1971) sought to manage population and car growth by both catering for and managing car traffic. These plans debated freeways but did not discuss parking, although behind the scenes statutory minimum requirements continued.

The 1981 strategic plan for Melbourne did discuss parking at some length. It defined a parking “limitation” area, the central business district (CBD), where parking maximums replaced minimums. This system was two-tiered, with parking management in the CBD, and conventional parking policies in the rest of Melbourne.

This continues today, with sharp divisions inside and outside the CBD in terms of the shares of trips by car.

After 1981, parking disappeared again from Melbourne strategic planning, while parking requirements continued in statutory policies. The deregulation of planning in the 1990s did not extend to car parking.

Strategic goals and parking policies in conflict

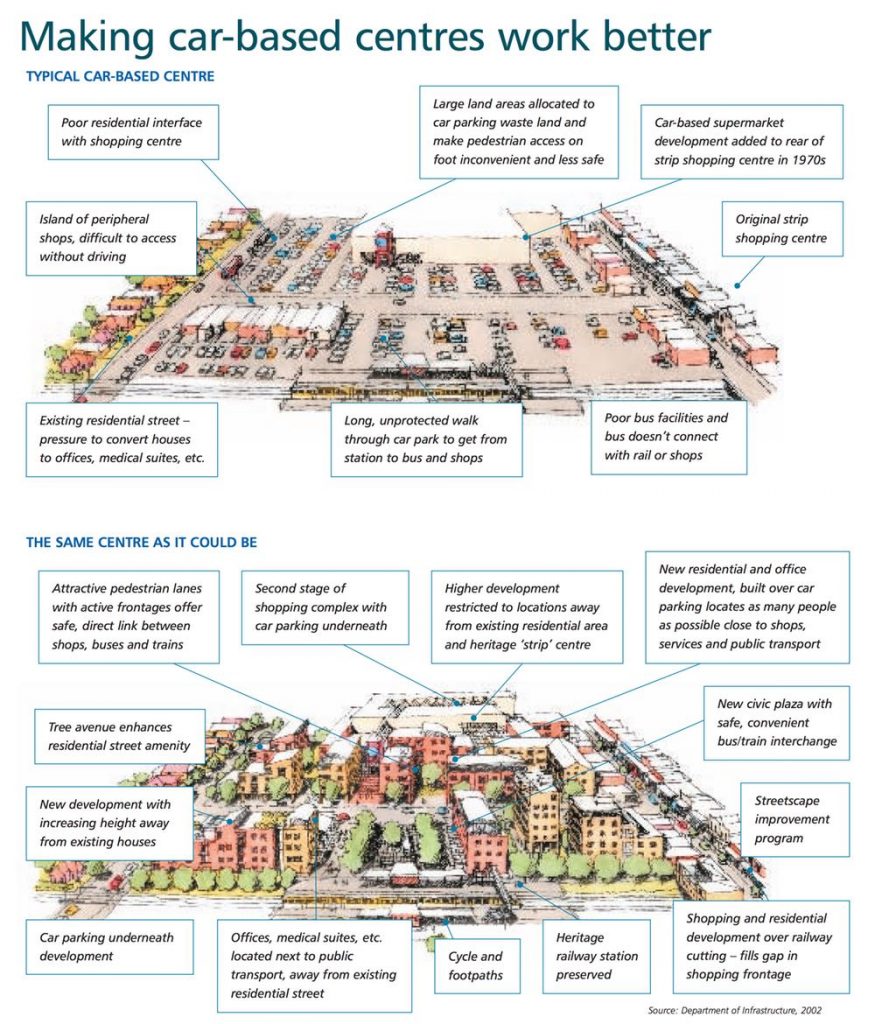

By the time of the 2002 plan, Melbourne 2030, strategic planning statements sought to increase urban densities and limit car use.

The document showed a “typical car base centre” surrounded by parking, almost identical to the suggested ideal in the 1950s. In 2002, however, this was contrasted with the same centre “as it could be”, with dense mixed development and tree coverage.

Despite a change in strategic vision, minimum parking policies remained. The 2014 strategic plan, Plan Melbourne, made essentially no mention of car parking.

Even with more recent strategic planning to curtail car use and increase urban densities, parking policies introduced in the 1950s to achieve the opposite effects have essentially remained intact.

The result is a complex and contentious system, with tensions between strategic policies (which encourage housing diversity and alternatives to cars) and statutory policies (which default to minimum parking rates). This fuels battles over car-free developments, such as Brunswick’s Nightingale and Commons housing projects, and fears about on-street parking competition, which are a major focus of Victoria’s planning appeals.

The post-war approach continues to shape Melbourne – its urban form, density, transport and housing markets. The idea that enough parking can be planned for is politically appealing. Minimum off-street parking and free on-street parking policies are standard, the latter often asserted as a kind of “folk legality”.

While parts of Melbourne built before parking requirements are in high demand (Victorian-era housing in Carlton or Fitzroy would never pass parking muster now), many Australians are also protective of the parking landscapes built by planning.

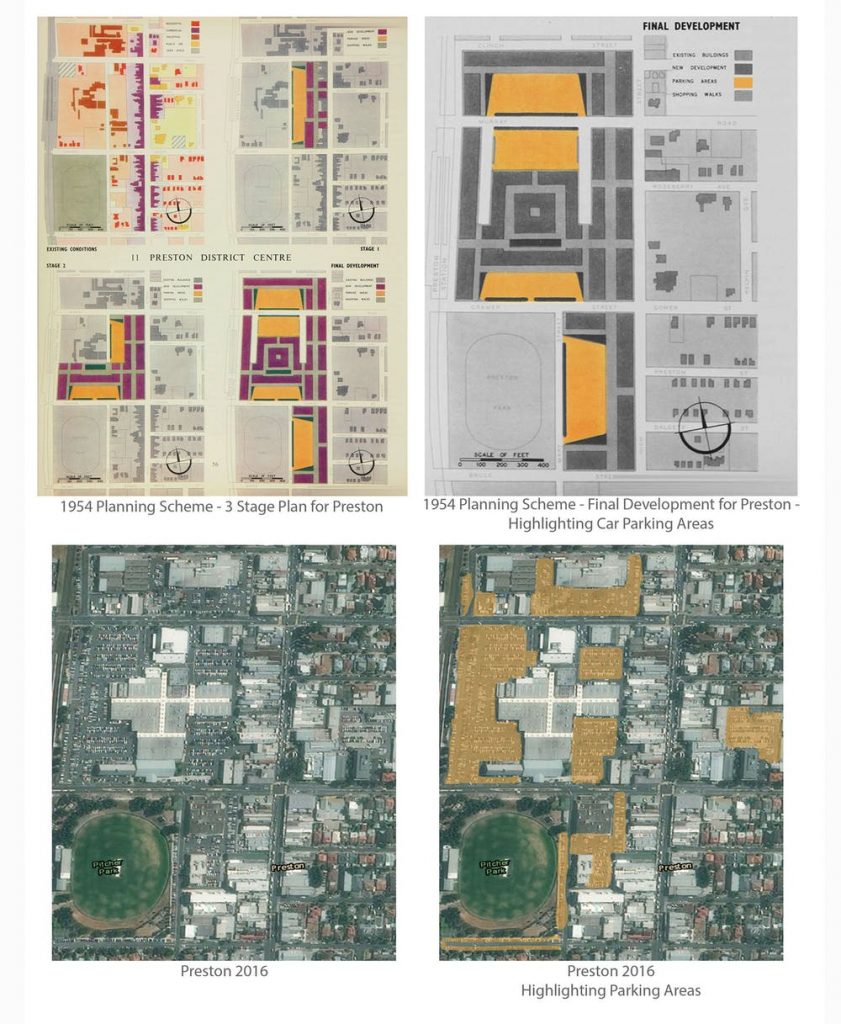

For example, a diagram in the 1954 planning scheme suggested remodelling Preston to include around 20% of the suburb’s area as surface car parking.

Aerial photography today shows this plan was implemented. Recent approval of an apartments project will, however, lead to the loss of some of these thousands of parking spaces. The development encountered fierce opposition for this reason.

Political sensitivities win out over strategic goals

While politically appealing, conventional approaches to parking do not withstand empirical scrutiny.

In The High Cost of Free Parking, Donald Shoup argues parking minimums oversupply parking and are based on a “pseudo-science” of spurious data and assumptions. Shoup argues the direct and indirect costs of parking (including land) are absorbed into development and housing costs, subsidising car users over other land uses and transport modes.

He asks:

“If urban planners want to encourage housing and reduce traffic, why tax housing to subsidise cars?”

Shoup and others argue for removing off-street requirements, introducing demand-based pricing of street parking, and using parking fees for local improvements.

Much parking research argues that managing on-street parking directly, including through pricing, would be fairer and more efficient and reduce the many adverse effects of conventional policies. Public reactions to parking meter fees suggest this is easier said than done.

Melbourne’s history shows that while post-war planning used generous parking policies to build car-dominated cities, strategic planning now plans around parking issues (most likely to avoid political fallout). Beyond the CBD and the efforts of some local governments there is little evidence that research or best practice is informing parking policies.

Parking minimums are powerful tools for realising strategic urban plans − if, as was once true, the goal is maximising car traffic. If aspirations for cities have shifted, it is time to reflect on the practice of planning around the parking “elephant”.

Parking will likely become more contentious as competition for space increases (partly due to cars pushed onto streets by garages used for household storage), along with new technology such as car and ride sharing, autonomous vehicles and peer-to-peer parking applications.

Some cities – London, Oslo and Zurich among them – are actively restricting parking. Australian cities could begin by reassessing the widespread requirement for off-street parking.

All that land set aside for parking is also an opportunity to ask what the real value of parking space is; who should pay for it; and whether using public space for the storage of private vehicles is the best outcome we can hope for.

This feature originally appeared in The Conversation.