For the better part of a century, home ownership has been the foundation of the average American’s growth in net worth and the cornerstone of the government’s housing policy. But 70 years of consistent appreciation in housing values, combined with stagnant real wage growth, has caused a nationwide crisis of affordability in major cities, and an intensification of wealth and racial inequality.

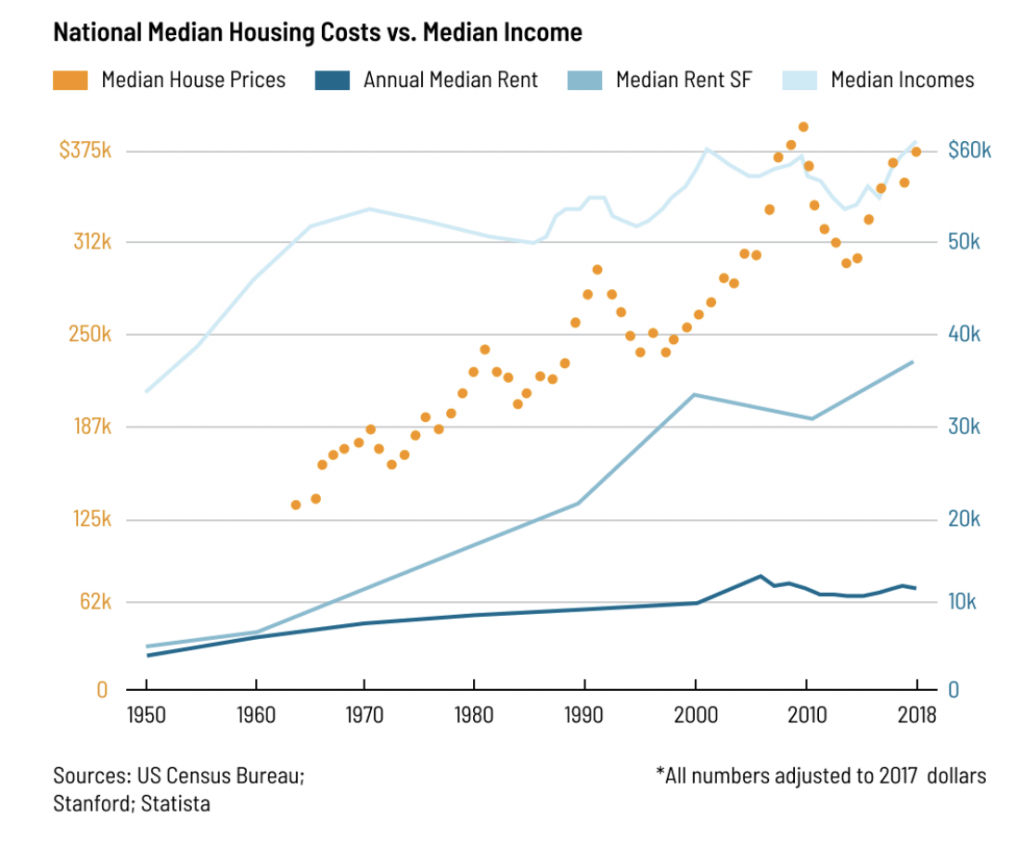

In just two generations, homeownership in the United States has improved by 20 percentage points, according to US Census data. But young people now are struggling to afford the same homes their parents could afford at their age. In cities such as San Francisco and New York, a consistent 2.5% annual appreciation above inflation in housing prices and rents has resulted in a quadrupling of housing costs since 1950 and homelessness rates not seen since the Great Depression.

Housing, like student loans and health insurance, has fallen into a free market trap. There’s an inelastic demand – everyone needs housing, an education and to be healthy – and people will pay almost anything to acquire these basic needs. In 1950, the median home price was 2.2 times the average yearly income. In 2013, a few years after the worst housing market crash in a century, median home prices had already risen to 3.7 times the average income. Largely, this inflexible cost has been paid for with greater private debt. Between 1949 and 2018, mortgage debt as a percentage of GDP grew from 15% to 80%.

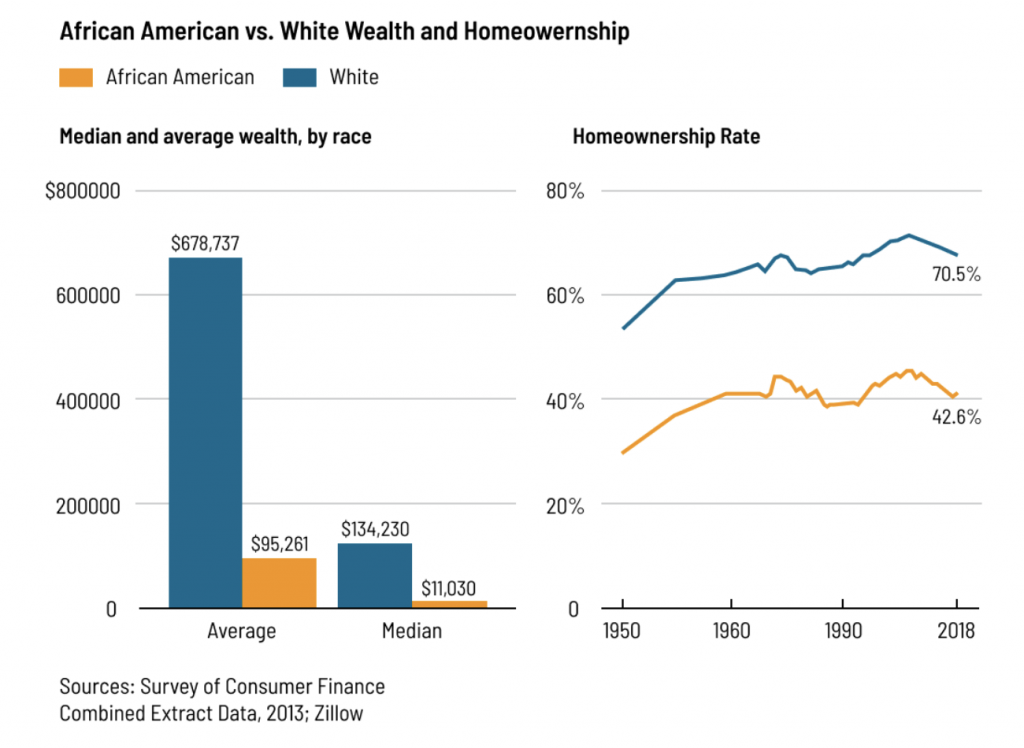

As with higher education and preventive medicine, those with the earliest headstart and least barriers to entry reaped the greatest rewards. While homeownership rates among white Americans have increased from 50% to 70% since 1950, African American homeownership has only risen from 30% to 40%. As a result, the median white American family’s net worth is now 12 times that of the median African American family, with two-thirds of that net worth attributable to home equity. And the racial wealth gap is growing: by 2053, African Americans will see their median household wealth fall to zero, just from being on the wrong end of housing appreciation.

From our partners:

The real world consequences of racial income inequality are playing out in San Francisco, where African Americans represent 34% of those experiencing homelessness, while only making up 6% of the city’s population.

Mr. D, an African American Bay Area native, worked in construction in one of San Francisco’s booming neighbourhoods. He built a life and a family in the city, but in 2015 he lost his job due to a leg injury. As is often the case, a combination of unemployment and the mounting costs associated with an injury soon depleted his savings and saw him evicted from his apartment. At 55 years old, he found himself with no home to call his own, living between shelters and sometimes sleeping in cars or friends’ garages as far away as Sacramento.

During this difficult time, Mr. D never lost hope. He went through a series of job training programmes, started a catering business, ran for office and volunteered with homeless community organizations. But after failing to find affordable housing for three years, he decided to pack up and move back to Texas, leaving his children and grandchildren in California.

The two institutions with the most to gain from housing appreciation – banks and the government – have fuelled the private housing market since mortgage terms were rewritten following the Great Depression. Banks have adeptly parlayed the human need for a stable home into trillions of dollars worth of profits. In the US, more than 90% of homes are purchased with a mortgage, and the average mortgage is worth 90% of the home.

For banks, the monopoly of the mortgage 9 market has allowed them to create a home-value arms race – the higher the value of the property, the higher the interest payments and potential profit. Even after the collapse of housing bubbles, government bailouts and favourable bankruptcy rules have limited the risk that banks face from limitless home value appreciation.

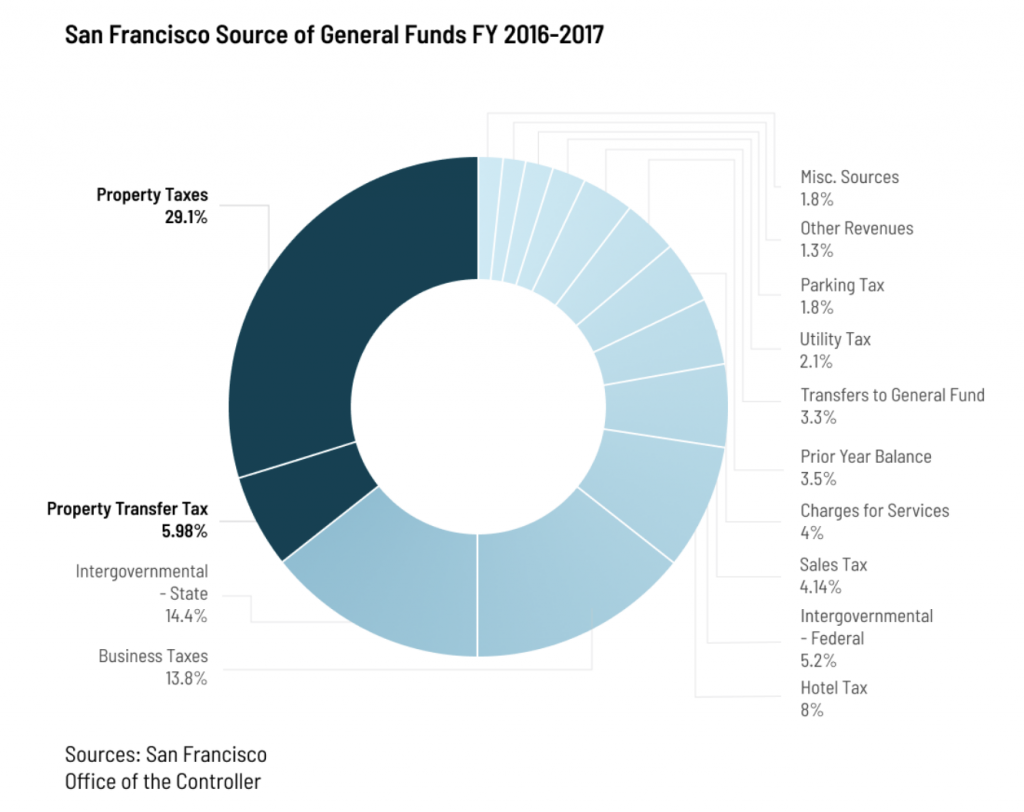

Governments, especially local governments, have a vested interest in maximizing property values. A booming homeownership market means rising net worths of the population and a steady source of tax receipts. For local and state governments, property tax is more important than income tax. In San Francisco, property tax accounted for 29% of the city’s general fund in 2017. By restricting redevelopment, building market rate apartments and condos, and allowing thousands of below-market units to be converted to market rate units, property tax receipts have ballooned.

Case Study: San Francisco

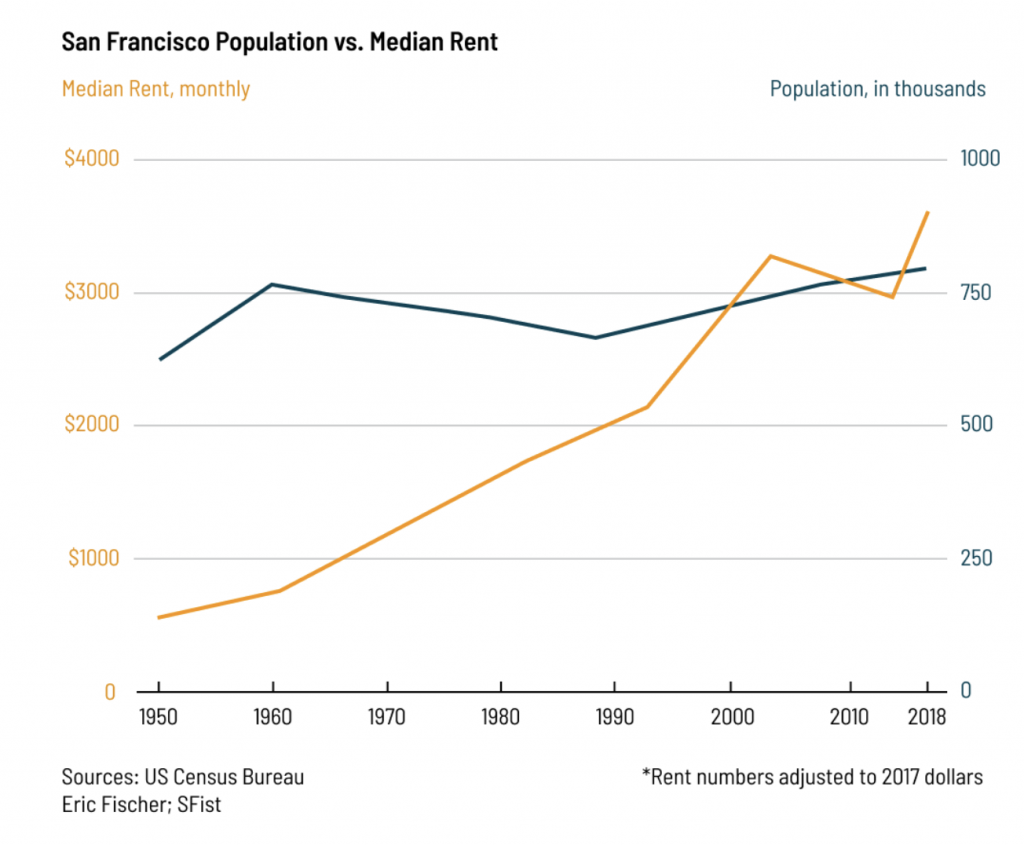

ShelterTech is a San Francisco-based non-profit that connects people experiencing homelessness with housing and human resources. They are building digital tools for underserved communities and have been studying the city’s housing crisis since their founder experienced homelessness firsthand in 2014. House prices, as well as median rents, in the city have been growing fairly steadily at 6.6% for the past 60 years—2.5% when adjusted for inflation.

For Mr. A, an advisor for ShelterTech and lifelong San Franciscan who was recently living on the streets, that means the three-bedroom apartment he used to rent with a roommate in 1980 for $750 a month now goes for $6,476, an 182% increase in 38 years after adjusting for inflation. Now that he’s 63, retired and living on his social security income, he’ll be moving into a subsidized housing unit that costs 58% of his monthly income. For him, however, this is still an upgrade from the conditions at the temporary housing and shelters where he had been living.

Pro-development advocates argue that massive new market rate housing development is the key to alleviating the housing crisis. It’s true: housing development hasn’t been keeping up with population growth at a regional level. But for San Francisco, the population in 2010 was only 3.85% greater than in 1950, while housing costs are nearly 400% greater. Housing costs have continued to increase regardless of the number of units built in a year or the fluctuation in the population.

Put simply, appreciation and inflation alone are such powerful drivers of the cost of housing that San Francisco would need to double the number of new units added per year to keep housing costs flat, ignoring population growth, wage increases, lower unemployment, and other factors that raise housing costs. To return to 1981 housing costs, the city would need to add an additional 200,000 new units or suffer a 51% drop in employment or 44% drop in median wages.

Another issue not addressed by market rate housing development is extreme income inequality, which is exacerbated by the relative inflexibility in rental costs. In San Francisco, the poorest 5% of the population earn just $650 per month, while the bottom 5% of rents is still $1500 per month. The city has built about 6,500 new affordable housing units in the last 10 years, but also lost over 4,000 affordable units due to owner move-ins, evictions, demolitions and conversions. In 2017, the city conducted affordable housing lotteries and received more than 85,000 applications for just 1,210 units.

Where do we go from here?

Improving renter protections, expanding social housing and more tightly regulating the mortgage market would slow down housing appreciation. Cutting down on short-term rentals and vacation homes also has a dramatic impact on housing affordability. In a recent study, MIT, UCLA, and USC found that for every 10% growth in Airbnb listings, a zip code’s average rent increased by 0.4%.

Another solution would be to limit foreign investment and speculation. When Vancouver passed a 15% tax on all sales to foreign home buyers, the price of single family property dropped 20% before rebounding, giving housing appreciation a short-term respite.

A more dramatic intervention would be to reverse the trend of corporations getting into the housing market and reintroduce public land ownership. From 2013 to 2015, corporations purchased almost $2 trillion worth of land and buildings in the world’s top 100 cities. Middle and lower-class families aren’t able to compete with corporate property investors, but local governments and community organizations could use collective buying power to play an active role in repurchasing large quantities of housing stock.

The Dutch constitution has a provision for providing adequate housing to its residents. As a result, the Netherlands currently has the highest share of social housing in the EU, accounting for about 32% of the total housing supply and 75% of the rental market. As the largest housing supplier, the Dutch public housing system is well-positioned to set market rates and address the country’s growing housing needs. It is an interesting example of a functioning large-scale social housing system in a developed country.

Written by

Derek Fidler, Co-founder, ShelterTech

Hicham Sabir, President, ShelterTech

Originally appeared in World Economic Forum.