Over 12 days at the start of October 2019 eight people were killed, more than 1,300 injured and nearly 1,200 arrested after demonstrations became violent in Ecuador. The demonstrations focused on reversing the ending of fuel subsidies, which had been brought in as part of austerity measures backed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The protests only ended when president Lenín Moreno agreed to restore the subsidies.

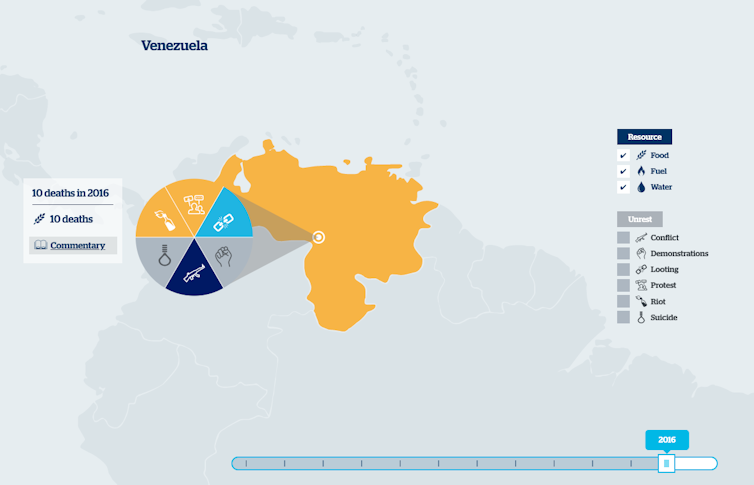

In the summer of 2016, the northern region of Venezuela was gripped by violence. The unrest was a result of a steep fall in oil prices, which led to severe shortages in food and basic necessities, as imports became unaffordable. Many were killed as they queued for food.

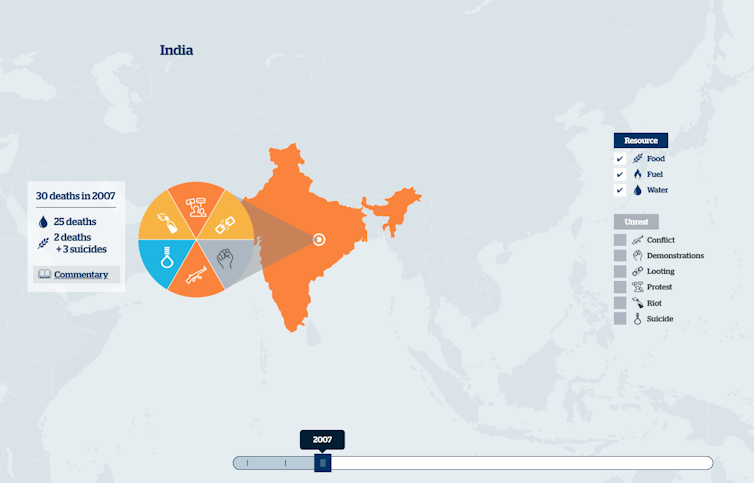

When a man set himself on fire outside parliament in Cairo over the price of bread in 2011, ensuing protests led to the collapse of the government. And during riots in West Bengal, India, in 2007, 300 people were injured and two were shot dead by police as villagers raged against a corrupt food distribution system.

So what links these seemingly unconnected international tragedies? Everyone needs food, fuel and water to live. It’s a fact of life. When these become scarce, it is inevitable that chaos follows – rioting, protest, death. This link to increases in death rate can be direct – through starvation or dehydration – or indirect, if they lead to a rise in suicide or violent social unrest. If indirect, there is usually a trigger which links back to the physical scarcity, lack of access to or mismanagement of these vital natural resources.

This has, of course, always been the case. Scarce food, water or fuel has always led to death. And in modern times people have been lulled into a sense of security when it comes to scarcity – at least over much of the world. It is often assumed that things are better than they were, that there are more resources and improved international protocols for sharing those resources when things get tough. But is this really true? In the age of climate change, perhaps not.

From our partners:

Climate change is only going to worsen the chaos attendant on resource shortage – and, therefore, death rates. Increases in extreme weather will have adverse impacts on food production and water availability. Indeed, they already are. Meanwhile, fossil fuel depletion and unstable exporting regions will lead to huge increases in the cost of energy. Future food, fuel and water prices are at the very least going to be more volatile.

This will mean that an increasing part of the world’s population will find it more and more difficult to access fundamental resources. A vulnerable and usually poorer population will face real threats to life and livelihood. Stress will then become heightened if an individual or community experiences injustice or is living in an increasingly fragile state, with little expectation that things will change for the better. Hopelessness or anger may manifest, resulting in a need for answers and action.

To avert unnecessary deaths, mitigate social unrest and effectively manage natural assets, governments and states must devise policies and early intervention programmes in disaster risk management and peace-building. This isn’t something that needs to happen in the future – it needs to happen now.

Tracking chaos

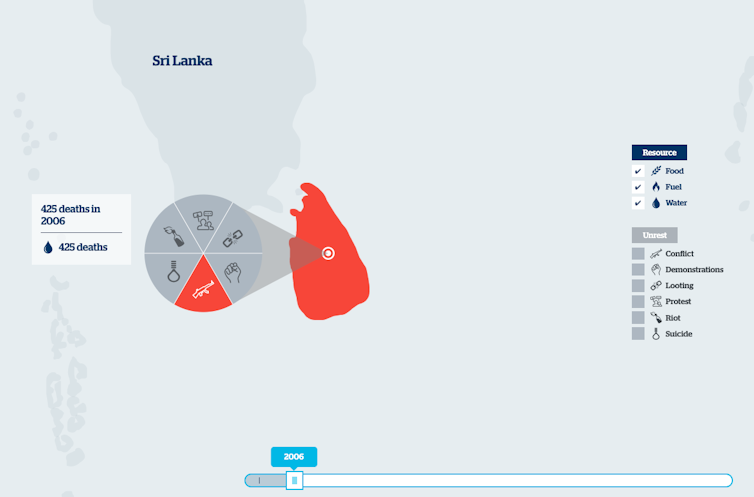

Of course, any attempt to do so needs to be based on historical examples of deaths caused by environmental stress. But the data on environmental conflict is rare and fragmented, making the study of conflict due to resource insecurity challenging. To fill this gap, we have launched an interactive map of such events over the last 12 years, illustrating that environmental stress is already causing chaos, globally. We define chaos as a combination of natural resource insecurity, social unrest and at least one death.

We sourced the data from news items, focusing on key search words, such as “food protest” or “fuel crisis”, to match events that include at least one reported death due to underlying food, fuel or water security issues. Out of a total collective “chaos figure” of 1,625 deaths over the period studied, 20% of deaths on the chaos map are attributed to suicide. The highest death toll was 425 in Sri Lanka, for a single event in August 2006 when Tamil rebels and the Sri Lankan army fought to control an irrigation sluice near Trincomalee.

This map is a pilot project and currently holds data on events up to 2017. But it something we aim to update and maintain in order to provide consistent open access data for the research community, as well as governments and NGOs. It could underpin their understanding of the trends that drive this type of chaos. The map shows that deaths linked to natural resource insecurity are already happening. We hope that by highlighting this we will increase the pressure on governments to develop food, water and energy strategies which take into account the likelihood of chaos and therefore build more resilience into the global and local economy.

The chaos events we tracked were not limited to sensational breaking news stories that make global headlines. We also covered less-publicised incidents, such as farmer suicides in Australia and the death of a woman during the Gilets Jaunes protests in France. These smaller incidents are as important to track as the major outbreaks of civil unrest as they highlight ongoing pressures in the food, fuel and water systems.

A conservative estimate

It is also likely that the data points we collected reveal an extremely conservative estimate of the reality of chaos around the world triggered by environmental insecurity. This is because a significant amount of under-reporting occurs due to delays between initial food, water or fuel access issues and eventual deaths through protest, or even censorship and a lack of media coverage (in English).

For example, while many commentators have since linked food insecurity to the early demonstrations that led to the Syria unrest, no individual news report explicitly links a particular death to those early demonstrations. Or at least no news report included both the food insecurity demonstrations and someone’s death in the same article. So there were no news reports in the database that we searched and this event is therefore not included in the map.

This highlights that episodes related to fuel or food insecurity which do not immediately involve death, can escalate, leading to other protests (potentially no longer directly linked to the underlying food or fuel insecurity). They can then cascade into much larger impacts, such as the Arab Spring or Syrian civil war, which of course led to thousands of deaths.

Alongside the data we collected, we have also developed a commentary series, selecting specific chaos events and gathering further information on the immediate context, how these events unfolded and the identification of reoccurring common themes. We hope that others will build on our work, diving into the particular issues associated with each recorded event to enhance our understanding of the compounding factors which lead to chaos and identify common conditions and triggers. This is crucial work to do in the context of the current climate crisis.

To demonstrate the forces at work, let’s consider two examples of the chaos points on our map. There’s the case of West Bengal, which saw food riots linked to changes in food price subsidies in 2007, and the case of Venezuela, which saw a change in fuel prices for export lead to food shortages – and then chaos. These two examples highlight how different local and international dynamics can still lead to similar chaotic situations.

Corruption in West Bengal

During the September to October 2007 food protests in West Bengal, India, 300 people were injured and two were shot dead by police. At least three food distributors were captured and told to pay fines. Unable to raise the cash and in combination with public shaming, they killed themselves.

How did this happen? India has systems set up that are supposed to deal with resource insecurity and hold chaos at bay. For many years, the country operated a Public Distribution System (PDS) which supplies essential commodities at a subsidised price through an extensive network of fair-priced shops to both rural and urban households below the poverty level.

But a central government investigation in February 2007 found that most rural poor in northern and eastern India failed to receive regular rations of food. It was found that rural West Bengal had the highest number of households below the poverty line and faced seasonal starvation, with 28% of household livelihoods rooted in agricultural labour. Rising wheat prices also prompted households above the poverty level to demand wheat rations from the PDS. The survey further revealed that food distributors were hoarding grain and selling it for premium prices on the open market.

For example, on at least two occasions in Radhamohanpur, West Bengal, villagers caught local food dealers selling subsidised grain outside the village. They reported this to the ruling Communist Party of India Marxist (CPM). But villagers felt that the CPM was not only protecting the dealers (as no action was taken) but financially benefiting from party donations from dealers’ growing wealth.

It was only a matter of time before poor villagers reached breaking point and on September 16, 2007, a perfect storm gathered. The national survey had confirmed the belief held by millions – of a corrupt system resulting in hunger and a widening gap between rich and poor.

They also believed the village leader and dealer were partners in ration theft and sought to formally present the allegations to the CPM leaders and put them under pressure to force them to take some action. A rickshaw cycle, microphone and a variety of slogans were organised by the villagers, who selected the most educated among them to communicate the slogans across four neighbouring villages where food dealers lived. The rickshaw gathered a crowd of 20 to confront the dealer but the CPM was sheltering them to avoid confrontation.

Up to 12 villagers entered a convention organised by the party leaders to voice their grievances. But they were told by the party there was no time to hear from them. A district council member urged the protesting villagers to do what they could as the dealer was inside the school. The crowd began pushing and shoving. When they saw that the crowd was turning against them, party members, who were standing behind a barricade, took out firewood and waved it aggressively at the crowd.

By this stage, the crowd had grown massively in size, with accounts ranging from between 1,000 and 5,000 – mainly male – villagers gathered outside the school.

When the police were called in the crowd turned violent. Stones and bricks were thrown at the party convention and at police officers. The Rapid Action Force (RAF) was deployed, firing blank rounds into the protesters who quickly dissipated. The RAF was forced to stay in the village for a month to keep the peace. But two deaths of protesters occurred and spill-over violence erupted in the neighbouring villages and towns of Murshidabad, Bankura and Birbhum.

Venezuela’s oil crisis

Food chaos can also stem from fuel crises.

The northern region of Venezuela, particularly the state of Sucre and district capital Caracas, was gripped by violence and ten deaths in the summer of 2016, and many more deaths in subsequent years. The unrest was a result of a steep fall in Venezuelan oil prices, which led to severe shortages in food and basic necessities, as imports became unaffordable.

Since taking office in 2013, president Nicolas Maduro had continued to follow socialist economic policies. But years of mismanagement left the country more dependent on imports. As oil accounts for 95% of Venezuela’s export revenue, the country took a major blow to its income when prices declined.

Following a decision to reduce imports of food and basic necessities to pay off national debts, a state of economic emergency was declared in early 2016. The resulting food shortages worsened and the ensuing anger led to unrest. The political opposition made efforts to call a referendum to oust president Maduro, but government councils stymied these efforts.

The armed forces were granted power to resolve social unrest and General Vladimir Padrino Lopez was promoted to minister of defence. The military took control of all food transportation and distribution, controlling prices and simulating production, in addition to guarding the ports, running Venezuela’s largest bank and managing a television station.

Unable to produce or import enough food for a population of over 30m, the looting of grocery stores and food trucks began. Hyperinflation of 200% was recorded in mid-2016 with people spending an average of 35 hours per month in food queues. Frustration at having to queue resulted in more looting. In one such incident, an 80-year-old woman was crushed to death in a stampede. Stationary queues resulted in muggings and shootings, despite the presence of armed soldiers.

The collapsed healthcare system and homicide rates of 90 per 100,000 residents meant Venezuela rivalled El Salvador as the world’s deadliest place. Thousands of Venezuelans travelled to Colombia in search of basic food and medicine. Violent outbreaks and riots from mid-2015 to mid-2016 saw over 24 killed while queuing, 30 injured and over 400 arrested.

Mapping future chaos

Climate change isn’t going away any time soon. Nor are issues like fuel shortages and social deprivation. It is likely, then, that trends in food, water and energy systems – including increases in demand – will see more volatility in prices and inequality in access. This is particularly true for key regions that may potentially become unstable (such as the Middle East or North Africa).

The links across different resources (food, water and fuel systems), different levels (local and global) and different dimensions (environmental, political and social) are clear. These links provide the network that allows shocks to cascade through the global economic system. For example, a collapse in fuel output in one location can trigger sudden increases in international prices of food which in turn result in widespread impacts and, in cases where politically fragile settings exist, chaos.

Society can better prepare for a more volatile future, or even help to reduce the likely volatility, by being guided by past “chaos events” and understanding the risk of environmental conflict around the globe before it escalates.

Previous examples show us that governments should better map key bottle necks in food and energy supply chains so they can prepare to respond when a future global shock causes increases in prices or a reduction in availability. Nations and states, meanwhile, need to have a water strategy that can forecast demand as well as understand likely changes in supply due to climate change or degradation (chemical pollution or salt water intrusion).

The international community needs to understand which countries are more susceptible to food and fuel price shocks so that aid can be proactively deployed to reduce this exposure. Being better prepared for such events should reduce the “chaos toll” and increase the effectiveness and efficiency of aid spending.

There are ways that migration and civil disobedience can be avoided. Given the right help and support, a community may be able to diversify livelihoods and develop alternative and sustainable fuel, food and water options.

Certain themes shine through that could inform possible local interventions. For example, the West Bengal case highlights the risks involved in government corruption, poverty and subsidies. A long legacy of distrust based on land-grabbing, theft of food rations and lack of response to village concerns in reporting the dealers for selling rations, was in place. Governments need to build trust, give space for a community’s legitimate grievances to be heard, support community voices to exercise their legal right to protest, and hold anyone guilty of corruption accountable for their crimes.

In the case of Venezuela, government mismanagement, military presence, inflation, reliance on imports and long queues were all factors. Seeking high-level agreements to suspend debt payments while requesting additional loans or aid from the international community and securing essential supplies would have been critical to tackle the medium-term crisis. Short-term solutions, like identifying queuing alternatives such as drop-in days by alphabet based on name, may have helped reduce chaos. An earlier intervention in this case would focus on diversification of national revenue away from oil. In addition, supporting local food and water security initiatives would build local resilience and reduce the potential exposure of communities to international prices.

The earlier effective interventions can be made, the more likely it is that the risk of chaos can be averted. Interventions generally require decentralised, democratic, participatory and representative models, that address the essential needs of those in the lowest socioeconomic groups. In tandem, adaptable plans that include energy alternatives, such as renewables, resilient and diverse food systems and integrated water management, should operate locally.

Our chaos map brings together data that can help inform thinking around the factors that lead to chaos. With better information, we can then work with people across the board – decision makers, academics, practitioners and local communities – to achieve a less chaotic system and, hopefully, reduce future death tolls.

Aled Jones, Professor & Director, Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University; Davide Natalini, Senior Research Fellow, Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University, and Imelda Phadtare, Visiting Research Fellow, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.