A new study finds a strong correlation between income level and canopy cover. But the solution involves more than just planting additional trees.

By now, researchers have well established the benefits of trees in urban neighborhoods. Trees are correlated with better health outcomes. They mitigate the urban heat-island effect and lower energy bills. They raise overall property values.

But how trees and their benefits are distributed across neighborhoods is a complicated picture. A new study published in PLOS ONE offers a provocative look across several U.S. cities at what neighborhoods are most likely to have urban tree canopy (UTC) cover. Money may not grow on trees, the authors write, but in a way, trees grow on money.

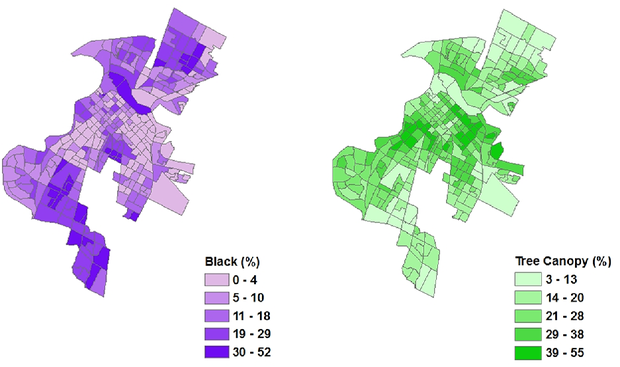

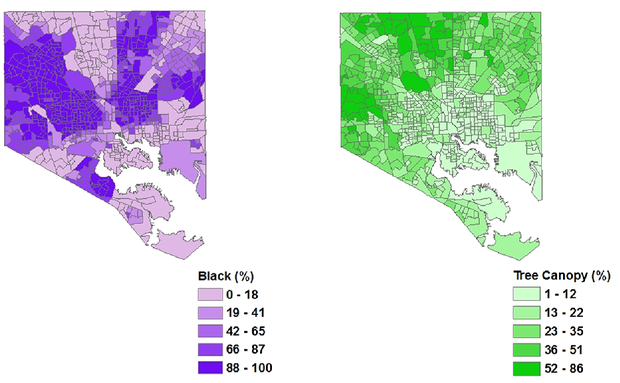

Led by Kirsten Schwarz, assistant professor of biology at Northern Kentucky University, the researchers used high-res land-cover data and census information to study the distribution of trees in relationship to race and income in Baltimore, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Raleigh, Sacramento, and Washington, D.C.

From our partners:

“Schwarz hypothesized she’d find a strong negative correlation between minority neighborhoods and urban tree canopy.”

Schwarz’s research is among the first to calculate, in a comparative way, what is most strongly correlated with tree density and distribution across multiple cities. Previous studies that examine tree cover and socioeconomic variables have mostly focused on single cities. There’s also been research to show that African Americans, Hispanics, and Latinos are more likely than whites to live in neighborhoods highly vulnerable to the urban heat-island effect—which is related to UTC cover, since shady trees can mitigate it.

Indeed, Schwarz and her colleagues hypothesized that they’d find a strong negative correlation between minority neighborhoods and urban tree canopy. In some places, like Los Angeles and Sacramento, they did find that. But in other cities—Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York for example—that wasn’t the case. Across the seven cities, the strongest link was income level, not race. Wealthier neighborhoods are more likely to have more and denser trees.

Why some cities’ trees have stronger correlations across racial lines might have something to do with climate. “In more temperate regions, a tree potentially will grow if it’s left alone,” Schwarz says. “But in more arid systems that’s not necessarily the case.”

In drier climates, like Los Angeles’ and Sacramento’s, it takes more water and more money to care for trees, which might amplify the socioeconomic differences, compared to more humid places.

This taps into a major, often unspoken, concern when it comes to planting in disadvantaged neighborhoods: Trees aren’t always an amenity. When it’s up to residents to take care of their trees—even ones that are put there by the municipality—it can be a cost and time burden, especially in places where water comes at a premium.

So, not only is it important for cities to factor in social equity when looking to expand tree-planting goals, it’s also crucial that they dedicate long-term support to make green spaces last. Philadelphia has done a pretty good job at linking environmental justice to sustainability plan. But most cities, with their meager forestry budgets, could step up their game.

“The resources need to be there, not just for plantings but for maintenance,” says Schwarz. “We need a longer view on maintaining tree canopies in the city.”

This feature is adapted from CityLab