Big cities are considered great engines of new ideas for good reason. Lots of smart people in a single place means many minds converging on the same problem. That leads some people to create fresh solutions—and it leads others to hear about these solutions early, steal them, and try to improve them even more.

But when it comes to innovation, city size may not matter as much today as it did in the past. That’s the argument made in a new working paper by researchers Mikko Packalen of the University of Waterloo in Canada and Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University. The duo writes that the “considerable advantage” once held by big cities on great new ideas “has eroded” in recent decades:

Our empirical findings indicate that during the 20th century inventions in large US cities built on recent advances much more often than comparable inventions in smaller US cities. The findings also indicate that during the most recent decades this advantage of large cities has waned. The advantage of locating R&D resources in large cities over locating the same resources in smaller cities thus seems to be much smaller now than it has been in the past.

Packalen and Bhattacharya performed a close textual analysis of U.S. patents granted between 1836 and 2010. They matched this data with population density figures for the inventor’s home location. Together those measures showed the researchers where inventors lived when they filed patents based on other recently patented concepts; in other words, they had a portrait of the role urban environments play in innovation.

Through most of the 20th century there was a clear connection between dense cities and innovative ones. But as the chart below shows, that advantage seems to have declined, rather considerably, over time:

From our partners:

The likely reason for the shift is as simple as it is predictable: digital communication. A connected world not only gives people wider access to new ideas, but it also gives people wider access to the discussion of those ideas—both types of exchanges that once occurred more often in person. Economist Alfred Marshall, a pioneer of innovation study, predicted as much back in 1920, as per Packalen and Bhattacharya:

“Marshall (1920) himself explored the implications of such ‘cheapening of the means of communication,’ and raised the possibility that location might play only a minor role in knowledge production as knowledge would ‘depend chiefly on the aggregate volume of production in the whole civilized world.”

But digital communication hasn’t eliminated city size from the innovation equation. The geography of U.S. innovation over the last decade shows that although patent activity doesn’t directly follow population size, major metros still tend to lead the way (after Silicon Valley). And Packalen and Bhattacharya find that U.S. inventors seem to use more new ideas than do inventors in other parts of the world—a sign that true global innovation hasn’t yet arrived:

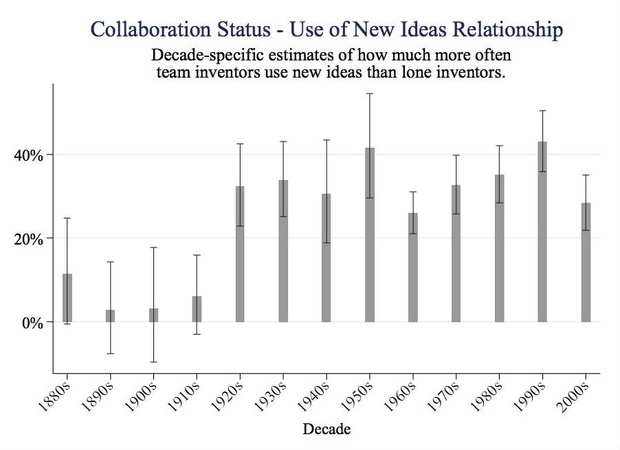

Then there’s the increasingly critical role of collaboration. Packalen and Bhattacharya find that over the years teams of inventors have become “much more likely to apply fresh knowledge than lone inventors”:

A looming question is whether all the members of these teams need to be in the same place to arrive at a great insight. If so, we might expect highly populated cities to remain hotbeds of innovation, given how quickly they can add brain power in person. If not, we might find more great ideas emerging from smaller places—either in full or in part—during the years to come.

This feature is adopted from CityLab