The New Urbanist neighborhood of Stapleton, Colorado, suffers from compromised planning standards.

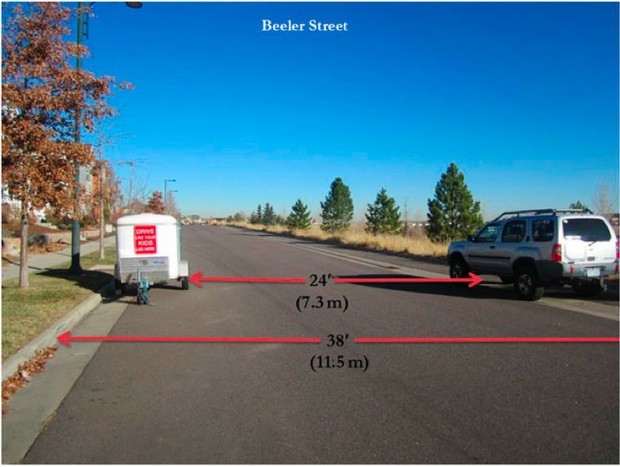

The above picture shows an example of citizen-led, “tactical” urbanism on a street in Stapleton, Colorado, a neighborhood just outside downtown Denver. A local resident has parked a truck on one side of Beeler Street and a trailer on the other, effectively reducing the road from 38 feet down to 24 feet, in an effort to get cars to slow down. On the back of the trailer is a sign that reads: “Drive like your kids live here.”

You might think Stapleton would be immune to stunts that call attention to car-first street design. It was, after all, envisioned as a New Urbanist neighborhood that emphasized compact development and alternative transportation. But the area undermined its planning ideals in the face of conventional traffic standards, says civil engineer Wesley Marshall of the University of Colorado at Denver, and the result has been an unfortunate case study in the hazards of design compromise.

“You don’t want to look at a case like Stapleton and say New Urbanism is a failure, because it isn’t really quite New Urbanism,” says Marshall, who not only studies Stapleton but lives there with his family. “In terms of the architecture and a lot of that stuff, it looks the part. But it doesn’t function that way. And a lot of the reasons it doesn’t function that way are specifically transportation related.”

From our partners:

Marshall recently outlined a number of Stapleton’s street design flaws, and the unintended problems they’ve created for the community, in the Journal of Urbanism.

A Planning-Implementation Divide

Stapleton was the primary airport for metropolitan Denver for most of the 20th century. When Denver International Airport emerged in the 1990s, Stapleton made a push to redevelop itself in a New Urbanist style, complete with the famed Peter Calthorpe as master planner. Initial plans for Stapleton explicitly called for a “variety of mobility options beyond the automobile” writes Marshall, as well as a reduction in vehicle miles traveled.

“In reality I think transportation is the key to getting New Urbanism right.”

But after analyzing the street network and street designs that Stapleton ultimately did implement, Marshall found a number of inconsistencies with respect to New Urbanist thinking. Here are some of the biggest (our emphasis):

- The street network is good at the neighborhood level, but it doesn’t connect very well to the larger city grid. That’s good for pedestrians and cyclists, but also means cars have to navigate a tricky maze of streets to leave or cross the area.

- The two main streets in Stapleton, Martin Luther King and Central Park boulevards, run right through the center of town. Ideally, major streets in New Urbanist developments would run on the periphery, to reduce traffic conflicts with non-drivers.

- Central Park Boulevard carries 12,000 vehicles a day, but it’s designed to hold 30,000 in anticipation of future growth. As a result, the road has way more space than it needs right now, which encourages faster traffic.

- Since most Stapleton dwellings have at least one off-street parking space, many streets (including Beeler) have lots more on-street parking than necessary, which has the effect of widening roads. Research has linked unused street parking with higher car speeds and crash rates.

- In accordance with Denver regulations, some major intersections (including those on Central Park Boulevard) have a curb radius of 30 feet—a “vehicle-oriented” value that’s generally considered by the standards of New Urbanism to be too large for walkable areas, since it facilitates faster turns.

“You get this intermingling of problems,” says Marshall. “If you have good connectivity and a dense compact connected network, it doesn’t work as well when you have wide roads where people can drive fast through them. You have to combine that with narrow streets and things that slow cars down.”

Faster Traffic, And More of It

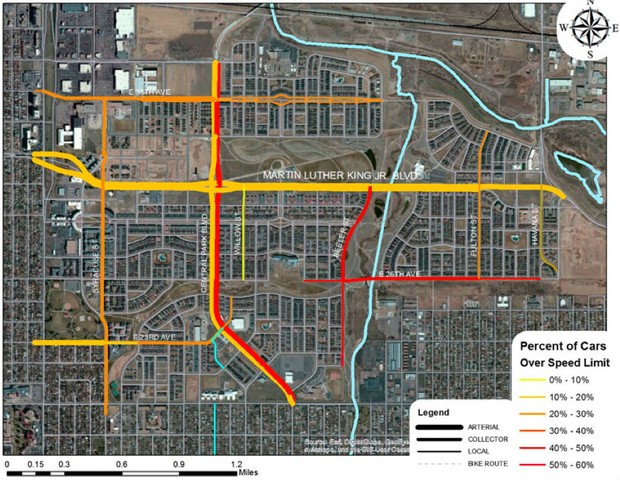

The problems with these street designs are already showing up in the local transportation measures. Marshall reports that vehicle speeds on the streets of Stapleton are “higher-than-desired.” Drivers on Martin Luther King and Central Park go an average of 18 percent and 22 percent over the posted speed limits, respectively, according to Marshall’s study. And on Beeler Street, with its glut of unused parking, more than 63 percent of drivers exceeded the 25 mph speed limit—some going twice that.

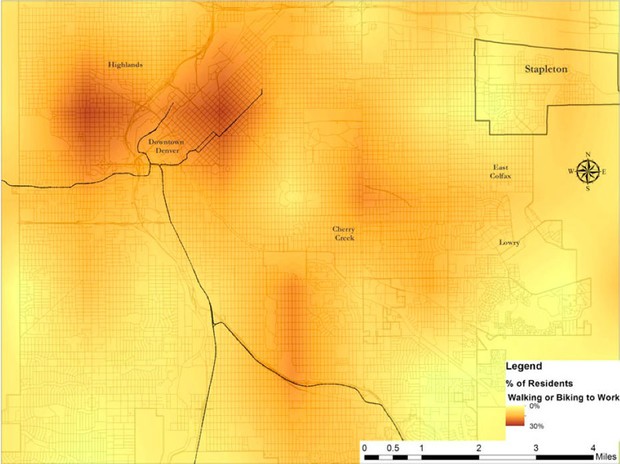

A travel mode choice analysis proved equally grim. For all trips, 92 percent of residents drive (with 98 percent commuting to work by car), 3 percent take the bus, 2 percent walk, and 2 percent ride bikes (this despite the fact that Stapleton residents own three bikes per household). Car reliance in Stapleton is notably worse than that of three nearby traditional urban neighborhoods: Highlands (77 percent of all trips by car), East Colfax (66 percent), and Cherry Creek (72 percent).

Transit use in Stapleton should increase once commuter rail reaches the area, and Stapleton residents do travel slightly farther to reach the Denver central business district than people who live in these traditional neighborhoods. But the high driving shares “are still somewhat unexpected,” writes Marshall. In addition to the street design flaws, he suspects part of the reason locals drive so much is that Stapleton’s mixed-use areas aren’t as spread out as they should be.

None of this is to call Stapleton a failure. The neighborhood might have “room for improvement,” writes Marshall, but it’s still an improvement on traditional suburban development.

Rather, it’s a cautionary tale about conforming to regional planning and traffic engineering standards that run counter to neighborhood goals. Marshall says it’s understandable that developers don’t want to fight city regulations every step of the way, and that cities themselves bear some responsibility in encouraging developers to reduce car reliance. Still, these decisions carry consequences that are difficult to overcome once a development is underway.

“New Urbanism has always been looked at as an architecture field, and transportation was a minor part of it,” says Marshall. “In reality I think transportation is the key to getting New Urbanism right. If you don’t get the transportation right, it’s not going to work.”

This feature is adapted from CityLab.