With harsh winters and a remote location, Jackson, Wyoming, has been unusually dependent on food trucked in from far away. Here’s how one company hopes to change that.

Known for its skiing and beautiful scenery, Jackson, Wyoming, experiences harsh winters in which temperatures remain below freezing—or below zero—for weeks at a time. The area’s lowest point sits 6,069 feet above sea level.

In other words, conditions in Jackson are not ideal for agriculture. But thanks to a team of local innovators, the town will soon enjoy high-quality local produce. How? A vertical greenhouse.

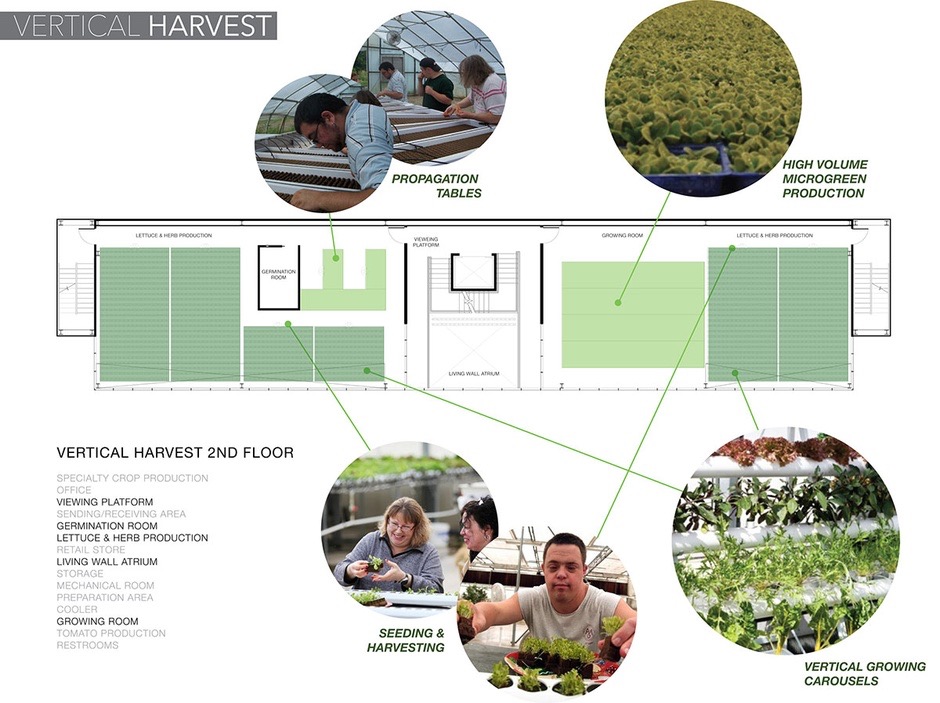

Vertical Harvest of Jackson Hole will be a three-story, 13,500-square-foot hydroponic greenhouse. It is situated on a skinny, leftover parcel of public land, 150 feet long by just 30 feet wide, next to a parking garage. The greenhouse will operate year-round and grow as much produce annually as would come from five acres of traditional agriculture. Ninety-five percent of Vertical Harvest’s eventual production is already under pre-purchase agreements with local restaurants and grocery stores.

“Ninety-five percent of Vertical Harvest’s eventual production is already under pre-purchase agreements with local restaurants and grocery stores.”

In his book The Vertical Farm, and in a number of TED talks (above video) and TV appearances, ecologist Dickson Despommier has proposed vertical greenhouses on a massive scale. He envisions high-rise buildings that would grow different crops on every level and serve major metropolitan areas. That idea remains mostly a conceptual one, but there are some vertical farms already in operation. Most of these are several stories tall but grow in one big, open space, as opposed to segregated floors. The plants in these greenhouses are situated on vertically revolving carousels to bring high-up plants down to the workers’ level for harvesting and care.

From our partners:

According to co-founder and architect Nona Yehia, whose firm E/Ye Design developed the architectural vision for the project, Vertical Harvest is unique in that it combines these two approaches to vertical farming. It is essentially three greenhouses stacked on top of one another. Each of the separate levels will grow different crops, with the first two floors looking more like traditional, single-level greenhouses. The top and tallest level will be akin to the other existing vertical farms. It will use rotating carousels to move the plants, effectively adding a fourth floor.

Vertical Harvest’s other co-founder, Penny McBride, is quick to point out that the greenhouse won’t feed the entire town, but it’s a first step toward finding a more sustainable way to bring produce to this and other mountain towns.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, of which the Jackson Hole valley is part, is one of the earth’s most intact remaining ecosystems. In that regard, Jackson Hole is an environmentalist’s paradise. But because locally grown produce is scarce, most fruits and vegetables are trucked in from afar. That is not only unsustainable, but impractical in a valley surrounded by mountains that receive an average of more than 400 inches of snow annually.

McBride recalls a major snowstorm that closed the few trucking routes into Jackson. “I walked into the grocery store and there were about two heads of cauliflower in the produce section,” she says. “Everybody was just standing around a little panicked and startled. It was a reminder of how much we rely on outside transportation to get our food to us.”

McBride recalls a major snowstorm that closed the few trucking routes into Jackson. “I walked into the grocery store and there were about two heads of cauliflower in the produce section.”

However, environmental sustainability is only part of Vertical Harvest’s mission. Even before it had a location or design, a key aim was to provide meaningful employment for local people with developmental disabilities. In Wyoming, their unemployment rate is 78 percent.

It was Vertical Harvest’s commitment to providing jobs for the disabled that helped to win over former Jackson Mayor Mark Barron, who recently stepped down after 12 years in office. Barron is also a business owner, and he makes a point of employing people with disabilities. “These are people who can and want to contribute,” he says. “And Vertical Harvest is a facility that will enable that to happen while providing a positive cash flow to its host community.”

Barron is now one of Vertical Harvest’s biggest supporters. “He wielded a big stick for us in the end,” says Yehia. But he was initially a skeptic, and he wasn’t the only one.

The former mayor was concerned about the feasibility of the project. “Glass buildings in the northwest corner of Wyoming aren’t typically energy efficient, and aren’t the smartest way to build. And then you throw a couple of floors into it, and this is an ambitious, risky business,” he says.

“Then there was the financial [element],” he adds. “Because if they failed, the town would be stuck with a three-story glass building. What the hell are we going to do with that?”

“If they failed, the town would be stuck with a three-story glass building. What the hell are we going to do with that?”

This is a particularly salient issue in Jackson Hole, where land comes at a premium. Ninety-seven percent of the land in Teton County, which encompasses the town of Jackson, is federally owned and protected. This includes Grand Teton National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Bridger-Teton National Forest.

The scarcity of available land, combined with Jackson’s popularity as a vacation destination, drives up prices. The average sale price of vacant land in 2014 was $1,160,000, according to Jackson Hole Real Estate Associates. Only three lots out of the nine available within the town of Jackson are listed for less than $500,000.

“When [the city] put up the parking garage,” Barron remembers, “we fully intended to one day put a project there to take advantage of that leftover space, something that would benefit the Jackson community.” Ultimately, it was the cofounders’ tenacity that converted him. “They went through one of the more gruelling, painstaking public processes that I’ve been involved in. But they would identify every obstacle from any angle, then they would overcome it.”

The women also won over Ed Cheramy, a leader of the local Tea Party. Initially doubtful, Cheramy, along with Barron, ended up helping Vertical Harvest make a successful bid for a $1.5 million grant from the Wyoming Business Council.

“The women also won over Ed Cheramy, a leader of the local Tea Party.”

Early on, McBride and Yehia used a combination of grants and funds raised from the community to conduct a feasibility study and secure a greenhouse engineer, Thomas Larssen. Larssen has built profitable greenhouses in places far more extreme than Jackson, like Siberia and Greenland. With his expertise, they were able to fine-tune crucial details. They also hired a third-party firm to conduct an energy study, and it verified Larssen’s projections. (“It was reassuring for us that we were on the right path,” McBride says.) Another challenge, even for Larssen, was that the town of Jackson lies within an area of high seismic risk. The need for a steel super-structure drove the budget up to $3.7 million.

The founders hope Vertical Harvest will be a national demonstration project. If a vertical greenhouse can be commercially viable even under these conditions, it will conceivably be far easier to implement in other parts of the country. Other municipalities and organisations have contacted Yehia and McBride to find out if the model could work for them.

Vertical Harvest broke ground in December and expects to be up and running by early 2016. Thanks to the efficiency of the hydroponic growing method, which requires no soil and uses 90 percent less water than traditional farming, the first crop of tomatoes, herbs, microgreens, and more produce should be ready to eat within two months of opening.

As for what might lie 10 years down the road, Yehia says: “Fifty. One in every state.”

This feature originally appeared in CityLab.