Cutting-edge archaeological tools are helping nations find the remains of missing service members and return them home.

Growing up, the writer Clay Bonnyman Evans had heard all sorts of stories about his mother’s father, First Lieutenant Alexander Bonnyman Jr. Evans’s grandfather had joined the Marines’ officer ranks during World War II, and in 1943, he learned he’d be taking part in an assault on the remote island of Betio (BAY-sho) in the South Pacific. The goal was to drive out Japanese defenders so the United States could use the island to launch attacks on other Japanese-occupied territories.

After Bonnyman and his troops stormed the beach at Betio, they dropped TNT where Japanese service members were hiding out, using flamethrowers to light the explosives. That flushed out more than a hundred Japanese defenders so that American forces could take control of the island, despite heavy losses. Bonnyman was felled by Japanese fire on November 22, 1943, and the military awarded him the Medal of Honor after his death. “By his dauntless fighting spirit,” the citation read, “Bonnyman had inspired his men to heroic effort, enabling them to beat off the counterattack.”

Though 56-year-old Evans, of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, had never met his grandfather, it was his greatest wish to find Bonnyman’s remains and bring him home to the United States. No one seemed to know where he’d ended up, though. A family member said Bonnyman was buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii, but that was never confirmed. Relatives eventually decided to have his tombstone inscribed with the words “Buried at Sea.”

Evans’s mission to find his grandfather got a major assist when he struck up a conversation with a man named Mark Noah. A commercial pilot with a consuming interest in lost U.S. service members from World War II, Noah had founded a private nonprofit organization called History Flight. He had made multiple trips to the South Pacific to unearth the bodies of lost Marines—one of a variety of efforts, both public and private, to recover missing service members around the world.

From our partners:

Evans returned to Betio multiple times over the years, sifting sand, cleaning skeletal remains, digging out burial trenches, and shooting photos and video. The more time he spent there, the more committed he became to Noah’s mission, even though the excavation team hadn’t yet found his grandfather. “Mark and I were in very close touch,” Evans recalls.

“We always talked about Cemetery 27 and that finding my grandfather might be a needle in a haystack.”

In March 2015, Evans got a call from Noah. He said History Flight’s team might be zeroing in on Cemetery 27. Would Evans like to join the excavation and document the recovery? Noah kept Evans updated on the team’s progress, and it wasn’t long before Evans went ahead and booked himself a flight.

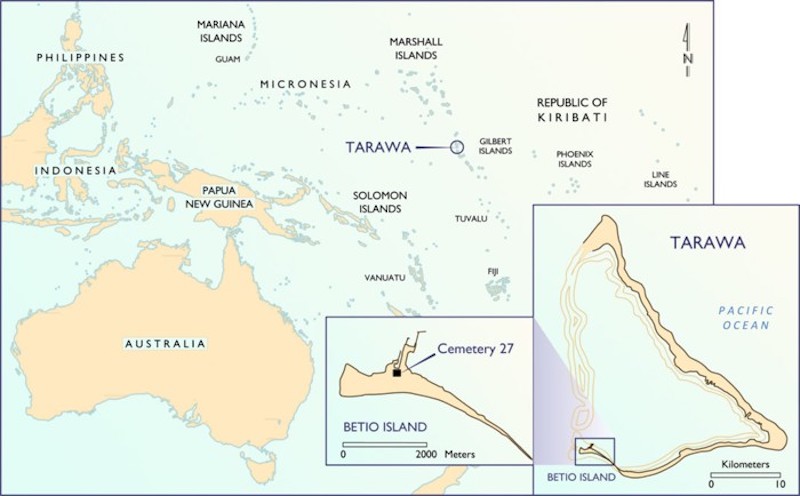

The island of Betio—a side jewel in the necklace-shaped Tarawa Atoll—has an area of less than one square mile, but it played an outsize role in 20th-century history. For centuries, Betio, part of the Republic of Kiribati, has been home to a small population of seafaring Pacific Islanders who fished to feed their families. Their descendants, more than 16,000 of them, still inhabit the island today and speak the traditional Kiribati language.

In late 1943, the U.S. command decided it needed to capture the nearby Marshall Islands from the Japanese in order to secure enough territory to launch air attacks from a land base. But to claim the Marshalls, the United States would have to capture a series of other islands first, including the Tarawa Atoll.

The United States assembled a massive invasion force comprised of a dozen battleships, 17 aircraft carriers, more than 60 destroyer ships, and over 18,000 Marines to take Tarawa and nearby islands. The frontline Marines who landed on Betio, Tarawa’s largest island, saw a tropical beach that was swiftly transforming into a hellscape. Battle strategists had failed to account for the low tide, so Japanese gunners on high ground were able to pick off many men as they struggled up the exposed beach. Others fell later on in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Altogether, more than 1,000 U.S. troops died in the 76-hour battle, and afterward, the waves around Betio were tinted red with blood.

These men’s sacrifices were not in vain—U.S. forces defeated the Japanese at Tarawa, setting up a string of other crucial wins in the Pacific. But in the heat of war, many service members killed in action had to be hastily buried on Betio. A body-recovery sweep in 1946 turned up the remains of 436 Marines, fewer than half the battle’s total casualties, and in 1949, the Office of the Quartermaster General designated the rest of Tarawa’s missing “unrecoverable.” That meant hundreds of families thought they’d never be able to bury their loved ones. Families were told, variously, that service members had been buried at sea or in unmarked graves.

That lack of closure was what got to Noah. As a commercial pilot and aviation-history expert, he had lent his knowledge to missing-persons recovery cases involving planes. Seeing the grief families felt for their missing relatives, who were often service members, Noah resolved to use his flying skills to aid the recovery cause. “We started doing airplane rides and using [them] to fund the search for the missing,” says Noah, who founded History Flight in 2003. “While we started doing that, it became very apparent there was a tremendous need for this kind of work.”

Though Noah eventually stopped selling plane rides, his recovery mission continued, taking on momentum as donations poured in. Since 2006, History Flight has sent more than 100 recovery teams to World War II battle sites around the world, including Allmuthen, Belgium; Buschhoven, Germany; and Mili Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The organization has raised more than $6.5 million, much of it privately donated, to fund these searches, and Noah himself logs 40 to 60 hours of searching each week on a volunteer basis. In 2015, History Flight entered a public-private partnership with the government-run DPAA, which helps identify the service members History Flight finds.

In Tarawa, Noah recognized a peerless recovery opportunity. World War II–era military records showed that hundreds of service members were likely still buried on Betio. That meant a well-targeted long-term search effort could grant peace and closure to thousands of relatives. “The reuniting of the person’s remains with their family is extremely important,” Noah says. “Instead of being buried underneath a garbage dump or a parking lot, they can be buried in their home country in a cemetery.”

As Noah ramped up his Tarawa excavation plan, he got in touch with a number of archaeologists, including Agamemnon Gus Pantel, a Puerto Rico–based archaeologist who’d worked on other History Flight projects in Europe. Pantel had experience using ground-penetrating radar to identify burial locations, an invaluable asset to any team searching for lost service members. At Noah’s urging, Pantel joined the Tarawa team as a volunteer in 2012. He was moved by the chance to help bring service members home with the honor they deserved. “When you deal with MIAs, it’s very real, and these are almost contemporaries,” he says.

“Most of these Marines we find are basically just kids—people who gave up their lives and didn’t really have a chance to enjoy life.”

From the start, the team—which also included History Flight forensic archaeologist Kristen Baker—knew they were in for a tough slog, since others had explored Betio in the past and come up empty. But because History Flight’s team came armed with ground-penetrating radar, they had an advantage. This type of radar uses microwaves to map different kinds of material below the soil surface. Unusual objects in the ground send different patterns of energy waves back to the surface than the surrounding soil, and the radar’s antenna picks up and records these differences. With this information—considered alongside things like historical records and the findings of cadaver-dog searches—researchers can assemble a rough map of where bodies may be located, which allows them to focus on excavation sites where they are most likely to have success.

Beginning in 2008, teams of History Flight researchers had gone to Betio periodically to conduct radar scans of the island. On some of these trips, they brought along surveyors and historians to help them get the lay of the land, as well as a cadaver dog named Buster, who had been trained to sniff out human remains. As Noah and his team compared the evidence they’d gathered to World War II–era burial-location notes and maps, they grew fairly sure they’d found Cemetery 27. According to U.S. military records, at least 40 Marines—including Bonnyman—had been buried in this cemetery after the Battle of Tarawa, but no one had been able to find it since.

In early 2015, with maps and radar results in hand, Pantel, Baker, Noah, and the rest of the History Flight team returned to Betio to uncover Cemetery 27. The team sweated for long hours under the scorching tropical sun to dig in the most promising spots. The work was even more brutally difficult than usual, since thick concrete pads—the remains of wartime installations—covered much of the cemetery. To dismantle the pads, the team had to unleash an arsenal of heavy equipment, including concrete saws, jackhammers, and a backhoe. “Our people work 14 to 16 hours a day,” Noah says. “We went through about 50 to 70 centimeters of concrete, and about 50 centimeters of crushed coral rock below.”

But chewing through the rock-hard barriers proved worthwhile. As the concrete and coral fragments gave way to finer grains and rich dirt, Pantel knew just how close they were getting. “You had a very clear whitish coral sand, and then all of a sudden you had this dark soil literally defining the burial trench. It just jumped out at you,” he says.

Soon after that, the team started turning up telltale dog tags, long bones, and even uniforms. One by one, Marines killed at Betio emerged from the soil, many of them almost perfectly preserved. As difficult as it had been to demolish, the thick concrete had kept Cemetery 27’s occupants largely intact. To figure out the identity of each man, the team compared still-intact sets of teeth to the wartime dental records of known service members. Other clues like identification tags and inscribed cigarette lighters also helped. Ultimately, the History Flight team retrieved the bodies of at least 35 Marines from the cemetery’s trenches—the largest war-related recovery ever completed at a single site.

Evans, his video-recorder light on, was there to document the whole thing. Based on wartime burial records, the History Flight team had determined that Bonnyman was most likely in grave number 17. Baker, the recovery team’s leader, was very confident Bonnyman would be found exactly where the record stated. As they inched closer to the grave, Evans’s nerves threatened to get the best of him. “I had a lot of time to really think about it: ‘Wow, I can’t even believe we’re coming this close.’”

The first indication that the crew had found Bonnyman was a glint of precious metal. “My grandfather had this extremely distinctive dental work,” Evans says. “Kristen saw the gold on this tooth—a kind of unusual-looking filling. She just said, ‘It’s gold.’” As it dawned on Evans that he was actually seeing Bonnyman face-to-face, he dropped his camera, completely overcome. “I had to try to regroup.” (Evans’s book about his search, Bones of My Grandfather: Reclaiming a Lost Hero of WWII, is slated to come out in July 2018.)

After History Flight makes preliminary identifications like these, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and the DPAA step in for the next phase: DNA testing to confirm each service member’s identity. Most often, the DOD contacts a known living family member to request a DNA sample. If there are maternal relatives, technicians extract the sample’s mitochondrial DNA—long-lasting genetic codes that are passed down from mother to child—and read the genetic codes using a machine called a sequencer. When a relative’s mitochondrial DNA sample matches that of a recovered service member, the DOD can state with confidence that the person belongs to a particular family line. (If necessary, other types of DNA testing, like autosomal DNA or Y-chromosome DNA analysis, can also be used to confirm service members’ identities.)

Even as the identities of the Cemetery 27 service members were being confirmed, History Flight’s excavation team was forging ahead in its search for the hundreds of Marines still missing. In the two years since the Cemetery 27 find went public, the team has found dozens of other Marines in various locations on Betio, including in garbage pits and pigsties. This year, project researchers are wrapping up their second-largest find—another cemetery, where 24 service members have so far been uncovered. Wartime documents mention other nearby burial sites that have not yet been excavated, so Pantel predicts other recoveries in the near future.

Still, as they search for the remaining service members on Betio, the researchers face ongoing logistical challenges. The Tarawa Atoll has a population density rivaling Hong Kong’s, and Betio’s landscape looks much different than it did 74 years ago. Wartime bunkers have been turned into latrines and animal pens, and residents frequently dig large pits to dispose of trash, which can disturb remaining burial sites. The research team is in a race against time to recover what they still can—especially since climate change threatens to bring on rising waters that could one day overtake the island.

To secure access to interred remains, the team often engages in delicate negotiations with residents whose thatched-roof homes line Betio’s shores. The locals have a deep appreciation for the island’s history and are often willing to assist researchers. “We always go into the communities—we meet with the mayor, the police department,” Pantel says. “We don’t want to come in invading their privacy or their cultural tranquility.” If the team needs to remove a row of plants or dismantle a fence to uncover a burial site, they either restore the site themselves or compensate the homeowners. History Flight says it’s also working with Tarawa’s cultural-heritage department to put up displays about the significance of bunkers, gun emplacements, and other battle relics that remain.

Beyond adding to the historical record, what matters most to the History Flight team is granting families the peace they have sought for generations.

“Closure is more than just putting someone to rest. The unknown is very disconcerting,” Pantel says.

“You have comrades, nephews, nieces, grandchildren who still don’t know what happened to their relatives. These are very real pains that families still feel.”

Family members say their loved ones’ homecoming has helped ease some of that pain. Betsy Gore Bond of Pembroke, Kentucky, found out through a surprise phone call that History Flight had located her missing uncle, Private First Class Ben Hadden Gore, in Cemetery 27. Her uncle’s return and burial, she says, brought family members closer together and strengthened their sense of their own history. “It’s like something you never even imagined happening to you.”

Evans, too, says the impact of a physical reunion can’t be overstated. In the hours after Bonnyman’s body was first uncovered on Betio, Evans was mostly able to keep it together—he didn’t feel comfortable letting his emotions out with so many people around. It wasn’t until the day after the recovery, as the sun rose over the quiet excavation grounds, that he let his guard down completely. “I went back over there by myself, and I sat down. It was between me and my grandfather, and that’s when I decided to have my moment in private.”

This feature originally appeared in The Atlantic.