Scarce, unaffordable housing is not a local problem in a few places, but is baked into the 21st-century global city. It’s time for cities, nations, and global leaders to start acting like it.

From reading the press, you’d think the housing crisis is mainly relevant to superstar cities like New York, London, and San Francisco. But housing is becoming increasingly expensive in a wide range of cities, including Philadelphia and Detroit. And the worst of the housing crisis by far is not in the wealthy cities of the advanced world, but in the rapidly urbanizing cities of the developing world, where hundreds of millions of people live in substandard housing, lacking electricity, running water, or basic sanitation.

The global housing crisis reflects a fundamental paradox of contemporary capitalism. Cities around the world are more economically powerful and essential than ever. This creates tremendous demand for their land, leading to escalating housing costs and competition.

Meanwhile, housing has been financialized and turned into an investment vehicle, which has caused an oversupply of luxury housing and a lack of affordable housing in many cities across the world. The global housing crisis is defined by a chronic shortage of housing for the least advantaged, and in many cases, for the working and middle classes as well.

Although increasing the housing supply and strengthening renter protections are necessary and important steps, cities alone cannot address the deep structural problem of housing affordability. Where possible, higher levels of government and international development organizations will need to step in to rein in financialization and provide the affordable housing that is so badly needed. But if past is precedent, cities will remain stuck with many of these burdens, and will have to come up with creative solutions to this crisis.

From our partners:

The housing crisis in the developed world

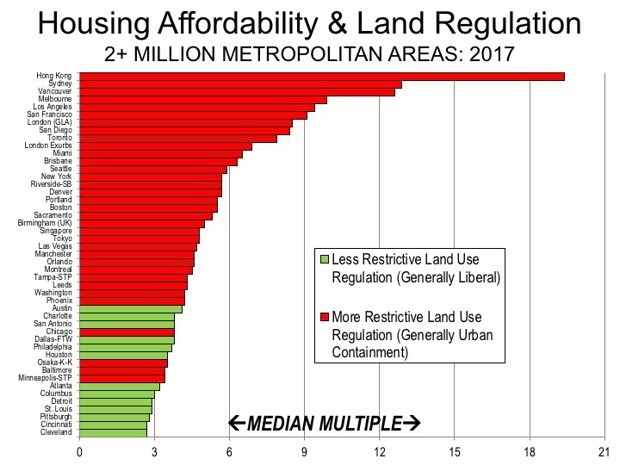

Let’s start with the best-known aspect of the crisis: the affordability crunch in the world’s most expensive cities. The chart below shows the world’s most unaffordable cities, based on 2017 data from Demographia. Their unaffordability is calculated based on a clever metric called the “median multiple,” which is a ratio of median housing costs to median incomes. This metric allows for straightforward comparisons of the multiple of income devoted to housing in cities around the world.

The world’s most unaffordable housing markets are not New York, London, and Los Angeles, or even San Francisco, but Hong Kong, Sydney, Vancouver, and Melbourne. London, Toronto, and Brisbane are also high up the list. Housing is also terribly unaffordable in Tokyo, Singapore, Shanghai, Beijing, Moscow, Paris, Stockholm, Amsterdam, Geneva, Rome, Milan, and Barcelona, according to other studies.

Several factors appear to be driving the housing affordability crisis of the advanced world. Expensive cities have simply not built enough homes to keep up with growth in employment or population. There are many well-known reasons for this, including NIMBYism, restrictive land-use polices, and the constraints of geography. And, of course, we have seen a sweeping urban revival and the rise of winner-take-all urbanism, in which talent, technology, and other economic assets are densely packed into a small number of neighborhoods.

A 2018 report on European real estate trends by PwC and the Urban Land Institute calls urbanization “perhaps the most significant influencer of real estate strategies in recent years.” In the United States, not just tech startups but established companies have been moving their headquarters to downtown areas. Coca-Cola recently moved 2,000 of its suburban employees to a downtown Atlanta skyscraper; General Electric moved its headquarters from suburban Connecticut to downtown Boston; and McDonald’s is moving its headquarters from the suburbs to downtown Chicago.

While the advantaged members of the knowledge, professional, and creative class have enough money left over even after paying the cost of housing in these cities, it’s the less-well-paid members of the service and working classes who get the short of end of the stick, with not nearly enough left over to afford the basic necessities of life. They are either pushed to the periphery of these places or pushed out all together.

Many of the less advantaged are renters, not owners. Owners were essentially able to lock in their housing costs at the time of purchase, and thereby benefit from significant appreciation. And rents have increased even faster than housing prices in many metropolitan areas. Indeed, rents in the U.S. increased by 22 percent on average between 2006 and 2014, while average incomes decreased by 6 percent. This has meant escalating rent burdens, which, again, fall heaviest on the least advantaged. Nearly half of all renters across America are “cost burdened,” spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing. And nearly three-quarters of households earning less than $15,000 per year devote more than half of their income to housing.

Little wonder that homelessness is growing across the U.S. The homeless encampments springing up in prosperous places like Orange County, California, and Seattle are reminiscent of the all-too-common informal settlements of the developing world.

The housing crisis in the developing world

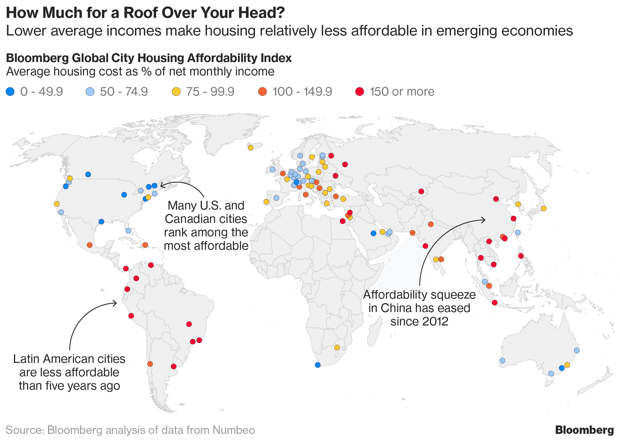

The most severe aspect of the global housing crisis by far is the housing situation faced by some 850 million people—more than the populations of the U.S. and the European Union combined—who live in informal settlements. The map below from the Bloomberg Global City Housing Affordability Index shows that as bad as the housing affordability crisis is in expensive cities, it is even worse in the rapidly urbanizing cities of the Global South, where rents as a share of income average 100 percent, 150 percent, 200 percent, or even higher. The most expensive and desirable cities in North America and Europe are far more affordable by comparison.

According to this metric, the most unaffordable cities in the world are all in the Global South—cities like Hanoi, Mumbai, Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Rio de Janeiro, where housing costs exceed 200 or 300 percent of incomes. The most unaffordable city of all is Caracas, whose economy is in a tailspin. There, average housing costs exceed incomes by more than 3,000 percent.

With as many as 200,000 people pouring into the cities of the Global South every day, it is projected that the number of people who live in informal housing will exceed 1 billion by 2020. The housing crisis of the Global South is compounded by the troubling rise of “urbanization without growth.” In the past, urbanization supported the development of local industries needed to support growth, like manufacturing, brick-making, and food processing, which in turn supported the growth of a middle class. In today’s globalized economy, these local connections have been sundered, and those activities can and do take place virtually anywhere, leaving cities split between affluent knowledge workers and the truly disadvantaged.

The global financialization of housing

It’s not just industry and services that have become global, but housing as well. In the past, housing was built and paid for locally. Even in advanced economies like the U.S., local savings and loan institutions, like the community bank Jimmy Stewart worked for in It’s a Wonderful Life, provided the bulk of financing for housing up until the massive financial deregulation that began in the 1980s.

But with the creation of new financial instruments related to housing, this local connection was broken. Housing, and especially its financing, became a national and then a global industry.

A 2017 report by the UN special rapporteur on adequate housing defines the financialization of housing as “structural changes in housing and financial markets and global investment whereby housing is treated as a commodity, a means of accumulating wealth and often as security for financial instruments that are traded and sold on global markets.” In other words, housing is increasingly intertwined with flows of global capital; housing markets are now more responsive to these flows than to local conditions.

The UN report estimates the total value of global real estate to account for 60 percent of global assets, with a value of $217 trillion, three-quarters of which is housing. That’s nearly three times the world’s total economic output. Since the Great Recession (which, ironically, was caused by real estate speculation), real estate markets have grown at a faster rate than many other financial markets.

As Saskia Sassen has documented, the main players in this market are giant corporations and private equity firms—in 2015, corporations purchased $1 trillion in real estate in the world’s top 100 global cities. Sovereign banks from countries like China, which recently relaxed its foreign investment rules, as well as oil-rich countries looking to diversify their portfolios, like Norway and Qatar, are also notable players in the global real estate market. Laurence Fink, CEO of the private equity giant BlackRock, said apartments in cities like New York, London, and Vancouver have begun to replace gold as the primary store of wealth for the super-rich.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect about the financialization of housing is the fact that all of the money being poured into housing markets has not contributed to a significant increase in supply, but rather to an increase in ultra-high-end units that are extremely expensive to produce. If even a portion of this global housing investment was “directed towards affordable housing and access to credit for people in need of it,” the UN report notes, the UN’s sustainable development goal “to ensure adequate housing for all by 2030, would be well within reach.”

In cities around the world, urbanization without growth has brought along a disturbing corollary: urbanization without housing. In the past, booming cities were able to accommodate massive influxes of new residents, but no longer. Today, the places with the most economic opportunity are too unaffordable for the people who would benefit from it the most.

When it comes to housing, even the most forward-thinking and aggressive cities have at best tinkered at the margins. Berlin created a universal rent cap for its low-income residents. Inclusionary zoning has picked up steam in may U.S. cities. The province of British Columbia, where Vancouver is located, instituted a special tax on foreign real estate investments. Tokyo has kept housing relatively affordable through extremely high rates of residential construction. In the much harder-hit cities of the Global South, some call for more expansion at the urban periphery; others call for better infrastructure; and still others call for empowering neighborhoods and communities to build more housing for themselves.

These are all worthwhile ideas with proven benefits, but ultimately, they may not be enough to alter the structural forces in play.

We must confront the fact that the global housing crisis is not something that is affecting one part of the world or another. It is baked into the very structure of our fast-urbanizing world. While factors like NIMBYism and land-use restrictions certainly exacerbate the housing supply and affordability problems of superstar cities, nearly all global cities are falling short on building enough housing, and enough functional, affordable housing, for those who need it most.

In order to correct this, we must no longer see housing primarily as a financial instrument or investment vehicle, but as a basic human right.

This feature is written by Richard Florida & Benjamin Schneider & originally appeared in CityLab.