We would like to thank our generous sponsors for making this article possible.

Even as China’s economy has surged following the dismantling of zero-Covid restrictions, youth unemployment has stayed stubbornly high. Part of the reason is probably because of a mismatch between the jobs young people are studying for and the roles that are available, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

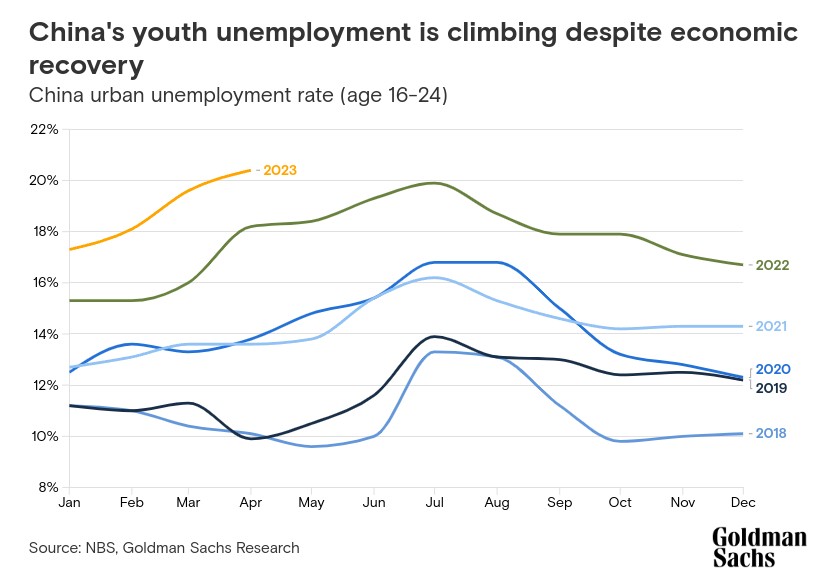

The overall urban unemployment rate in China is improving, but joblessness among 16- to 24-year-olds is bucking that trend. In April, it increased to 20.4%, nearly double the age group’s pre-pandemic level of about 10% in April 2019.

Young people tend to be particularly vulnerable during economic downturns, most likely because they have less work experience, Goldman Sachs economist Maggie Wei writes in the team’s report. That vulnerability may have been amplified by the pandemic, which was tough on service industries that tend to hire more young workers. And while the output gap (the difference between what an economy is producing and what it’s capable of producing) in the services sector narrowed materially in the first quarter of this year, the related increase in demand for workers probably won’t be enough to offset a pending flood of graduates.

The services recovery could subtract 3 percentage points from the youth unemployment rate in the current quarter, according to Goldman Sachs Research, but the strong supply of workers caused by graduation season could add 3 to 4 percentage points this summer before starting to decline from the end of the third quarter. “As a result, we might see youth unemployment continuing its upward trend in the next few months,” our economists write.

From our partners:

Goldman Sachs Research finds that mismatches between the skills graduates acquired from higher education and those required by employers are also likely contributing to the abnormally high rate of joblessness.

This misalignment is particularly acute in some industries. For instance, the number of graduates in education/sports disciplines grew by more than 20% in 2021 relative to 2018, but hiring demand among educational institutions weakened materially over the same period. Regulation changes in recent years impacting the information technology, education and property sectors might also have weakened the demand for labor in those sectors, according to our economists.

The stakes are high for correcting these imbalances, given how important the youth population is to China’s economy. This cohort spends heavily in areas such as culture and education, rent, transportation and communication.

The government has taken steps to promote employment for college graduates. Recruitment among the Chinese military recently prioritized college graduates, for instance, while the country’s state-owned enterprises have vowed to create 1 million internship positions for graduates over the next two years.

But even so, skillset mismatches can only be dealt with gradually. “Addressing the misalignment between school disciplines and business demand would help, but this is a difficult and medium-term task and unlikely to yield significant improvement in the short run,” our economists write.

Originally published at: Goldman Sachs