We are bombarded with statistics about the future of cities these days, as fast as the cities themselves are growing. More than half of the world’s population now live in a city, with the number of urban residents increasing by 60 million each year – that’s two new urbanites every second. It is a relentless rate of expansion that will see over 70% of the global population living in urban areas by 2050, requiring the equivalent of a new city of 1 million built every five days between now and then.

These mindboggling figures make impressive headlines for breathless reports on urbanisation, to be regurgitated at conferences across the globe, but such statistics are meaningless without asking what these cities will be like, who they are for, and how they are being made.

That’s why we are launching the Guardian Cities site, as an open platform for critical discussion and debate about the issues facing the world’s metropolitan centres, from the future of housing and transport, to public space and infrastructure;, from the nature of planning and governance, to energy and security – along with the forces of change that can’t always be planned for. What happens to cities subject to conflict and natural disaster, industrial meltdown and financial collapse?

Featuring regular contributions from established experts and new voices, we’ll be peeling back the glossy veneer of the computer renderings, and going beyond the facts and figures of the city sales pitch, to ask what our future cities will actually be like – and how we can influence them for the better.

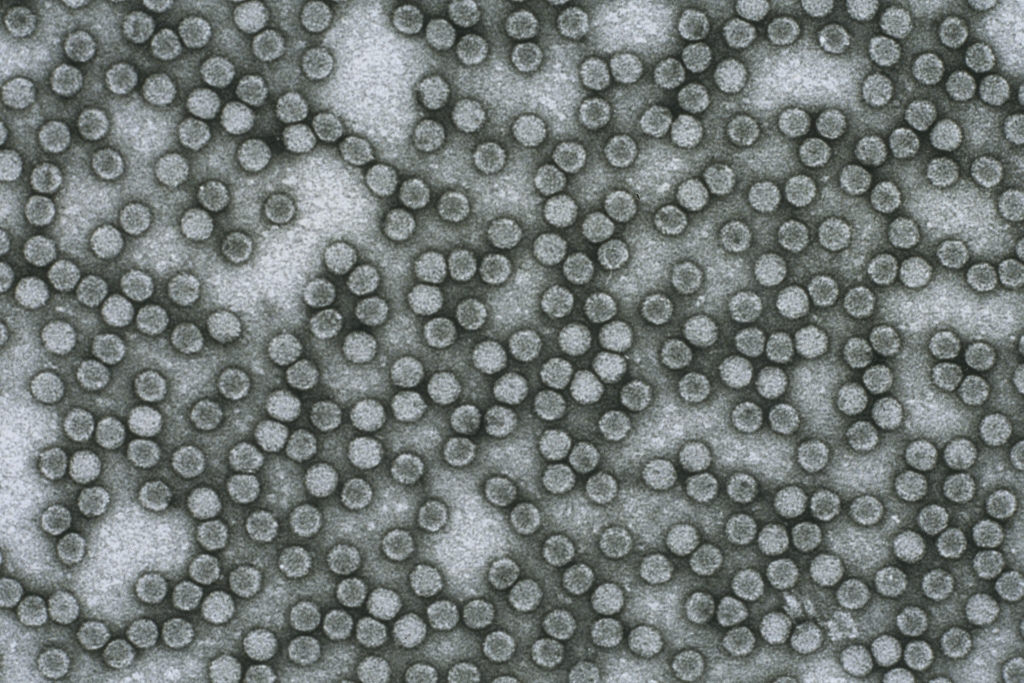

We are told that cities are getting “smarter”, as technology reaches further into our streets, bringing a brave new world of crime-fighting lampposts and sentient dustbins . Smart cities have been billed as the next leap forward, the arrival of networked systems for collecting, processing and implementing urban data hailed as a “second electrification” of the world’s metropolises.

From our partners:

No longer confined to programming traffic flows, the smart city’s sensors can detect its citizens’ daily routines, keep track of queues outside museums, monitor overflowing sewers, tell when dustbins are full and flag-up empty parking spaces. The citywide computer knows where it’s best to put the shops, where people should live, how much amenity space they should have, and when they are behaving suspiciously. The smart city can fix our mess, bringing order to urban chaos. But is outsourcing our collective civic intelligence to a computer algorithm the answer to making good places to live? And who sits in the control room?

As tech giants like Cisco, IBM and Siemens expand their influence on the urban realm, it’s worth asking who they are accountable to, indeed who owns the streets, spaces and infrastructure over which their systems keep watch. The “public” spaces, plazas and piazzas that come with urban regeneration are increasingly nothing of the sort, instead extensions of the private lobby, with public access contingent on activities and codes of behaviour that fit into the developer’s vision. As whole swaths of cities are sold off to private owners, returning to the model of the 18th-century great estates, whose vision are we signing up for? And do we fit in it?

Even where our streets and spaces do still remain in public ownership, their management is being progressively outsourced to private hands. The rise of the business improvement district across the US and Europe, visible in the growing number of branded wardens and guardians patrolling the streets, is creating new elite communities with the power to tax and the power to enforce the law, making separate cities within the city. As local councils slash their own services, is a return to feudal urban fiefdoms the price we must pay for cleaner, safer streets?

And are cleaner, safer streets really the ultimate goal? Town centres are increasingly looking to the shopping mall as the model for function, planning and management, the out-of-town retail complex standing as an idealised closed loop of contained, predictable systems. But when the mall is recycled as the blueprint for the town centre, is the chance and surprise of urban life being excluded for the benefit of efficiency and control? As high streets continue to decline, could there be more to the city experience than eating and shopping?

With risk and danger designed out of cities at all costs, conventional wisdom of what makes a good place is in danger of being overturned by the inexorable rise of security consultants. Under the influence of initiatives like Secured by Design, benign elements of the city are taking on new malign meanings: the humble bench is transformed from a useful place to sit down, into a potential source of loitering and antisocial behaviour. As counter-terrorist planning becomes the ultimate authority, our cities are being defined by blast distances and hostile vehicle mitigation zones, the urban realm reconfigured through a lens of fear. Are these new fortress cities making citizens safer, or merely more paranoid?

None of this will matter much if we can’t afford to live in the city in the first place. When housing has become an investment opportunity rather than a basic human right, and the majority of property bought overseas to let rather than owner-occupied, what is the impact on the city’s neighbourhoods and communities? How are architects, housebuilders and planners around the world responding to the urgent need for affordable homes, and what form will that housing take? Two billion people are projected to be living in slums globally by 2050; are our future cities places of inclusion and exchange, or merely tools for consolidating division and inequality?

With the fastest urban growth happening in developing countries, how far are the new city visions in line with the real needs of most people on the ground? Driven by local politicians and global investors eager to capitalise on the next frontiers, fantastical satellite cities are popping up across Africa and Asia, Russia and the Middle East. But do these specialised enclaves of science and technology, leisure and luxury, risk becoming white elephant ghost towns, diverting funds away from meeting the basic needs of the countries’ much poorer urban populations?

As cites expand ever upwards and outwards, whether hyper-dense or dispersed and sprawling, how will transport solutions adapt to changing patterns of movement? Are elevated cycleways the answer to commuting, or will they delay fixing problems on the ground and distract from the bigger picture of creating integrated streets for everyone? Will self-driving cars help to ease congestion and reduce accidents, or merely make drivers dumber and more complacent?

With urban growth outpacing our capacity to plan, the impacts of less predictable forces are also multiplied beyond all control. Facing threats of flooding and earthquakes, storms and tsunamis, the resilience of cities is tested to the limit, with any flaws in zoning and construction exacerbating risk. How far can such extreme conditions be mitigated, with protective infrastructure and disaster management, and should the way we live always be determined by the worst-case scenario? With flooding becoming an increasingly regular event, should we be retreating behind bigger barriers and steeper levees, or learning to adapt our cities to work with, rather than against, these conditions?

These are just some of the questions that the Cities site will be tackling, along with coverage of best-practice projects from around the world and interactive visualisations from the Guardian’s data team – as well as contributions from you.

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody,” wrote the American urban theorist Jane Jacobs in 1961, “only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” So come and get involved and join the debate.

This article originally appeared on The Guardian.