As America grew in the late 19th century, so did mapmaking—and Chicago was at the heart of it.

If there’s a capital of commercial mapmaking in the U.S. today, it’s probably in Silicon Valley. But from the late 19th century to the post-World War II era, Chicago was America’s city of maps.

Strategically located at the edge of the West, Chicago quickly became the country’s largest railroad hub in the mid 19th century, a position it exploited to tremendous economic and demographic growth. What began as a lakeside outpost with fewer than 200 residents in 1833 was home to more than one million people by 1890. By 1930, some 3,376,438 Chicagoans crammed within city limits of more than 210 square miles. The population peaked in 1950.

East Coast capitals like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston had led American mapmaking during the country’s first century, using European-derived techniques such as copper engraving, elaborate draftsmanship, and later, lithography. Two major lithographers, Henry Acheson and Edward Mendel, arrived in Chicago in 1853, securing the city’s mapmaking industry. Amid a booming publishing industry, booksellers also printed and sold maps.

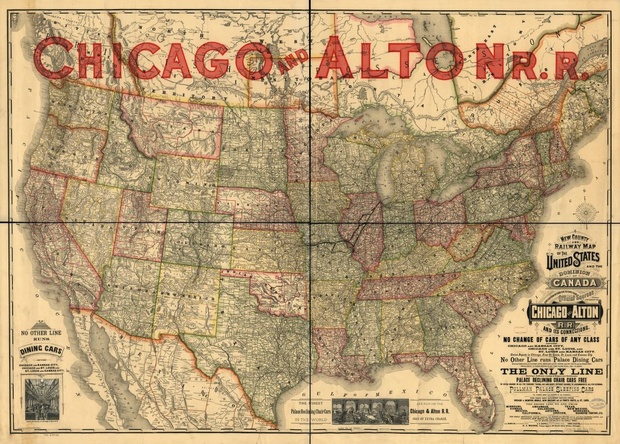

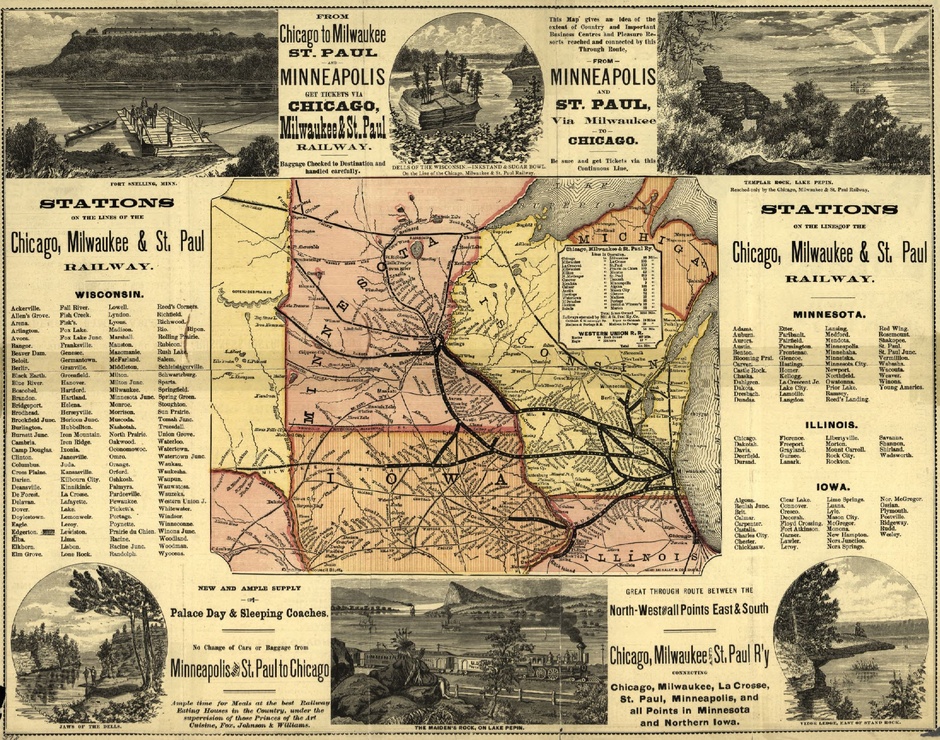

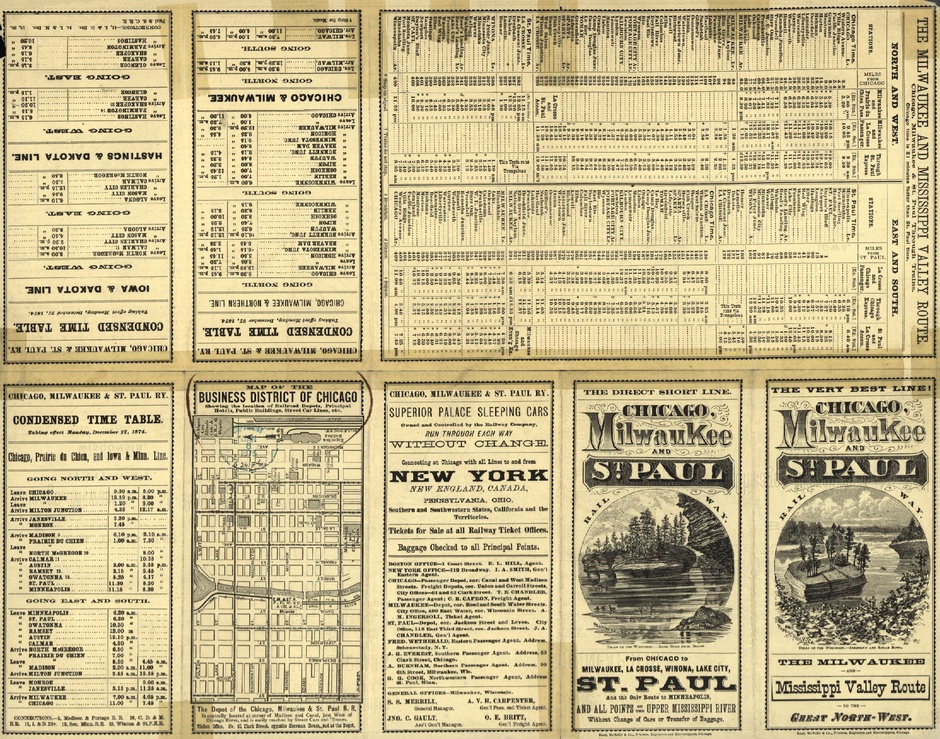

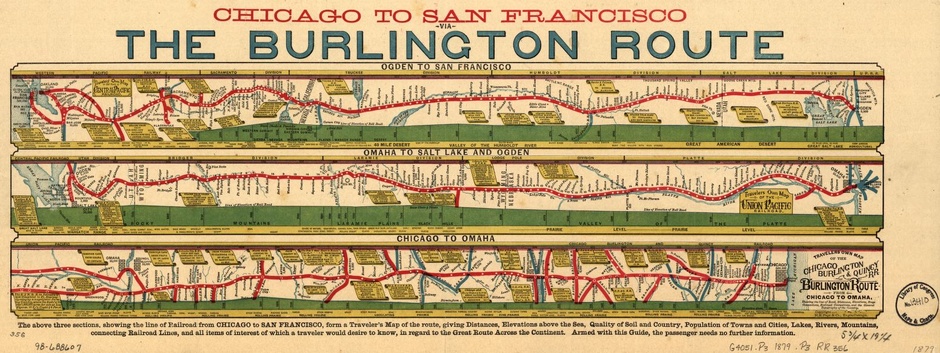

Yet it wasn’t until the birth of Rand, McNally and Co. and their quick grasp on burgeoning cartographic technologies that Chicago rose to nationwide prominence for the art and business. Beginning in 1858 as a printer of railroad tickets, Rand McNally soon began production of “railway guides,” which included route maps and timetables of different national railways. “As railroad lines were extending, new stations and towns were filling up the continent,” says Michael Conzen, professor of geography at the University of Chicago. “Maps needed to be updated all the time.”

From our partners:

To meet demand, the partners quickly seized on a new printing technique: cerography, or wax engraving. Unlike metal-engraving techniques and still better than lithography, cerography was easily malleable. It allowed for maps to be updated frequently and printed in mass quantities far cheaper than ever before—and in color.

With few serifs and a lot of practical information crammed onto the page, Rand McNally’s maps were far less fanciful and more “industrial looking” than their East Coast ancestors, says James Akerman, curator of maps at Chicago’s Newberry Library. “Simplified cartography for the masses reached its greatest early development in Chicago,” he says. It’s the same kind of all-purpose, slightly staid design Google Maps cherishes today.

!["Rand McNally & Co.'s new 12-inch terrestrial globe [gores]." Rand McNally and Co, 1891. (Library of Congress)](http://www.citi.io/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/161-5.jpg)

By 1917, Rand McNally had produced 30 different atlases alongside their booming railroad (and later highway) map business, which also evolved into a subscription service. Soon, that firm and others like the Poole Brothers, H.R. Page and Co., and George F. Cram churned out highway maps, city maps, tourist maps, advertorial maps, and globes. Bolstered by the city’s prime location, stellar printing industry, and keen business sense, Chicago’s map production soared.

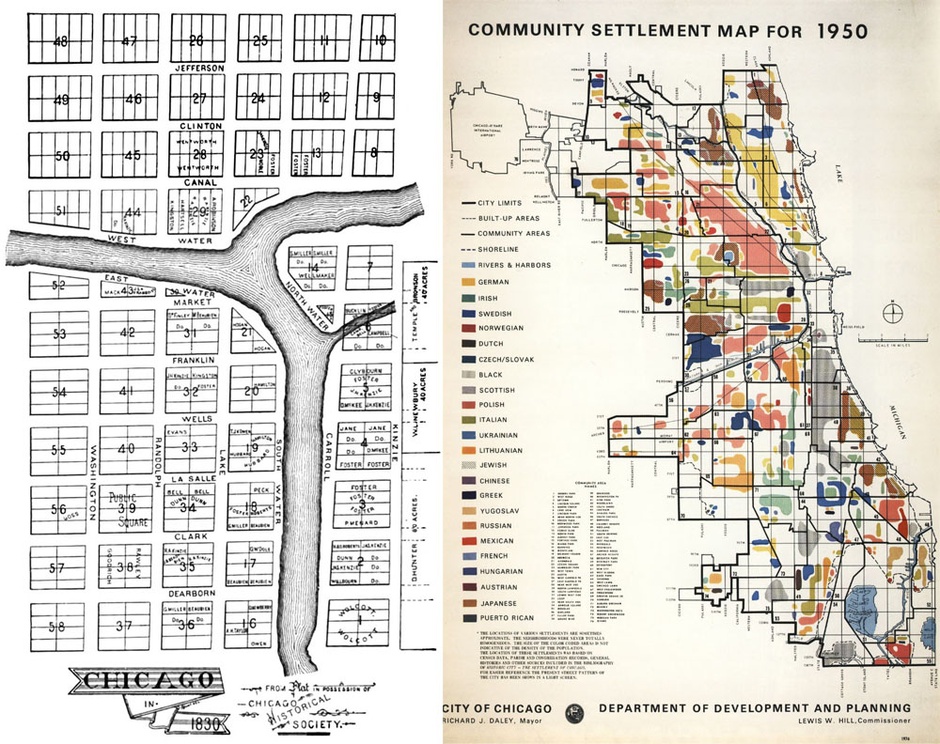

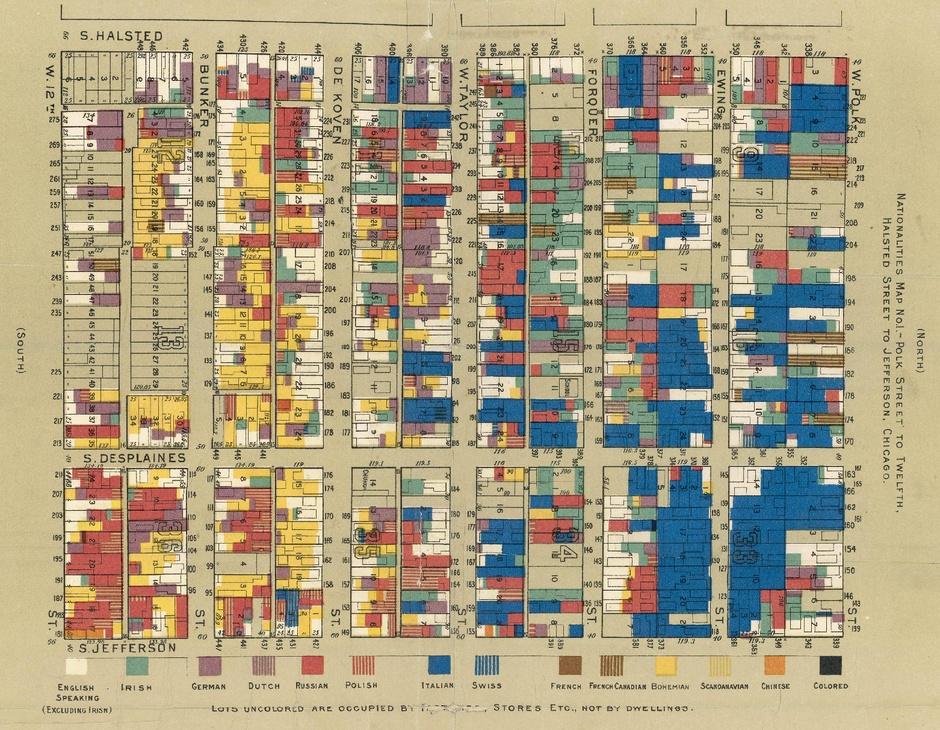

Notably, Chicago’s era of tremendous commercial mapmaking was contemporaneous with some of the most famous academic and civic mapmaking in history. Jane Addams’ Hull House pioneered statistical mapping to study overcrowding, the spread of disease, cocaine use, mortality, and much more beginning in 1895. Daniel Burnham’s 1909 plan of Chicago was first city plan “to express an idea about how a city should grow through a coherent set of maps and views,” says Akerman. Ernest Burgess’ “concentric circle” model, the first attempt to chart how American cities distribute demographic groups, emerged from the University of Chicago in 1923—a college designed during Chicago’s most ambitious years to rival East Coast Ivies in intellectual and cultural scope.

Though they largely kept apart from each other, Chicago’s coinciding academic and commercial mapmaking illustrated two sides of an exploding city: the grandeur of economic success for some, and the pain of societal ills for others.

“You have this great industrial city that’s very creative on a commercial level and has risen rapidly to national prominence,” says Akerman. “At the same time, this is a city that is the poster child for urban problems in the industrial era.” (Think the Pullman Strike, muckraking journalism, and *Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.) Hull House and the University of Chicago became focal points for addressing the problems of the city. Burnham and his boosters reimagined it.

![Burnham, Daniel H., and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, the Commercial Club, Chicago MCMIX [1909]. (Wikimedia Commons)](http://www.citi.io/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/161-9.jpg)

Commercially speaking, “It’s easier to do business from wherever you feel like living, since everything is electronic,” says Madison cartographer Daniel Huffman. Now, “cartography is happening everywhere.”

This article originally appeared in CityLab.