For all its lushness, the state imports the vast majority of its food. Advocates like Hunter Heaivilin think they have the solution.

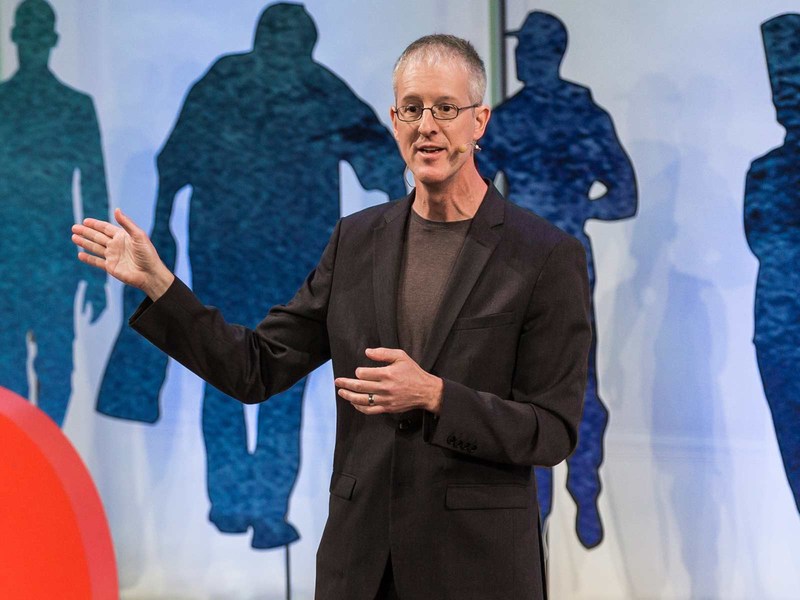

On a balmy January afternoon, as he drives northwest along Oahu’s sun-washed coast, Hunter Heaivilin happily explains his plans for creating an urban food forest in downtown Honolulu.

A full 2,400 miles from California, Hawaii boasts gasoline and housing prices among the country’s highest, but one of the state’s biggest imports—and a major factor in the high cost of living for its 1.4 million residents—is food. Estimates suggest that more than 85 percent of Hawaii’s food is shipped in from across the Pacific, while a 2012 study by the state found that “replacing just 10 percent of the food Hawaii currently imports would amount to approximately $313 million dollars which would remain in the State.”

With a 3 percent population increase since 2010, the state’s capital and urban centre of Honolulu, on Oahu, now contains nearly 400,000 residents, making it slightly more populated (and ergo, slightly hungrier) than Cincinnati.

Heaivilin, the director of three agriculture-focused nonprofits in Honolulu, was raised on Oahu and believes that its urban growth can be managed by making better use of Hawaii’s own natural resources.

From our partners:

“There’s an interest in having a tethering to the land,” he says, “but there’s a wealth of development in Honolulu, too. So how do we rectify destroying the landscape [with] all the benefits of urban spaces?”

In addition to the major crops of coffee, pineapple, and macadamia nuts, Hawaii’s farmers grow a number of native cultivars such as breadfruit, sweet potatoes, bananas, papaya, and taro (or kalo), the underground stem of which is ground to make sweet, paste-like poi.

These “canoe plants,” brought to the islands by waves of Polynesian settlers between 300 and 800 AD, have featured heavily in traditional Hawaiian cuisine, and now help to fill out urban garden plots alongside chili peppers, mixed greens, and various European and Asian vegetables. There are also examples of what Heaivilin and his peers call the “de-colonial palate,” including vegetables like edible hibiscus or “Samoan spinach” that are uncommon on Western tables.

While the islands’ isolation prevents much regional produce sharing, the state’s micro-climes allow for many kinds of crops to be grown year-round. Oahu itself has highland, lowland, arid, and lush zones, and a single tract of land from the mountains down to the shore might span different ones.

However, agricultural land is under pressure today. “Land value is high, so it becomes a lot more complex to keep land in agriculture—and people in agriculture—because of the cost of living,” Heaivilin says. While many people on Oahu have home gardens, the island is “still getting its feet wet” in terms of supporting an agricultural community.

Heaivilin and other core hui (or partnership) members of Hawaii nonprofits steer the urban ag movement. While Urban Farm Hawai’i and O’ahu Farm to School Network are working to expand resources for local growers and promote gardening and food education in schools, the Asia-Pacific Center for Regenerative Design (APCRD) and Permablitz HI offer courses and policy leadership informed by permaculture, an ethical design system for sustainable living and land use.

The groups have focused many of their latest efforts in the Kaka’ako neighbourhood of Honolulu, a previously industrial zone on Oahu’s south shore located between the tourist-heavy areas of Waikiki and Ala Moana and mixed-use Honolulu Harbour. Kaka’ako has undergone dramatic change as the site of large-scale and luxury development projects, but also, recently, a large homeless encampment.

On its new Kaka’ako plot, Urban Farm Hawai’i will kick off the first growing season with banana plants, a range of vegetables, and maturing taro stock that was removed from a previous site. The group hopes that the banana plants will provide fast shade for the growers in their new location, and that carefully managed irrigation and the harnessing of runoff water will help its green potential emerge quickly.

As Kaka’ako becomes more polarizsd by wealth, the garden projects aim to include all neighbourhood residents—including the homeless, through a partnership with the Institute for Human Services.

“It’s a leveling experience,” Heaivilin says. “Whether you’re from the penthouse or the pavement, you’re working shoulder to shoulder in the garden.”

By planting on urban infill sites, advocates hope to provide green conduits where both flora and fauna can reemerge. The projects also serve to “combat the extinction of [urban green-space] experiences,” Heaivilin says, and help urban residents re-learn to value them.

The ultimate goal is supersistence, livelihood above and beyond subsistence. Matthew Lynch, co-founder of the APCRD and Permablitz HI, is a “reformed capitalist” working alongside Heaivilin. He points out that high-rise developments in neighborhoods like Kaka’ako may raise larger environmental concerns; the building of high-density housing in a near-shore area will likely weigh on an already outdated and overburdened sewage system and other ageing infrastructure in Honolulu.

However, like Heaivilin, Lynch sees Kaka’ako’s growth as an opportunity to introduce more sustainable methods of development. “Everything is a resource,” he says, “and inherent in everything is an opportunity.”

This article originally appeared in CityLab.