Hailed as a housing solution for slums and a rapid response to disaster-stricken communities, 3D-printed architecture holds a lot of promise. But what problems lie behind its production, and can we realistically expect our cities to be printed?

The words “we print architecture’s future” adorn the wall of a showroom on the outskirts of Suzhou, a rapidly urbanising city in eastern China. Arranged around the room are samples of odd-looking concrete wall of varying thickness. Outside, across the car park of this otherwise unremarkable industrial estate, is a grand, neoclassical mansion that recently became a global internet sensation . It is the world’s first 3D-printed villa.

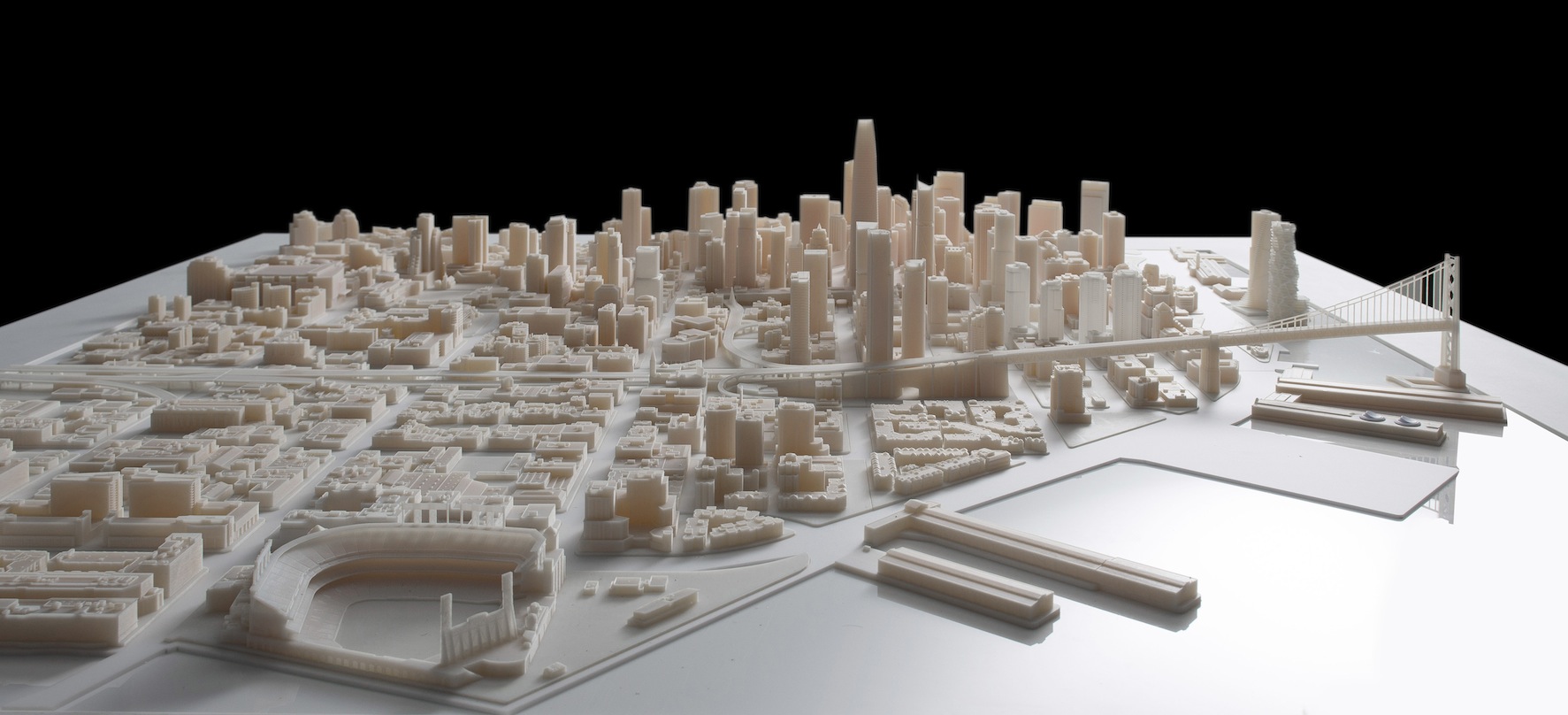

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing – the process of fabricating solid objects from digital models – has been around for three decades. Talk of how this technology could transform both the construction industry and the way we conceive of and build cities has long circulated, too. With 3D printing, customisable “dream” homes would no longer be the purview of the rich, and architects would be able to create fantastically complex geometrical structures. In the developing world, low-income housing could be erected en masse, while speedily printed structures would provide disaster relief or temporary homes for refugees.

But until recently such talk was largely theoretical. Then in March 2014, the little-known Chinese company Winsun announced it had 3D-printed 10 £3,200 concrete houses in a day. When, in January of this year, it unveiled that 3D-printed 1,100-square-metre villa – and a five-storey apartment building – it raised the question of whether the technology was about to become commercially viable.

In Winsun’s showroom, a video on a giant LED screen shows a printer head moving horizontally along a massive gantry frame. Winsun’s 3D printer is 6.6 metres tall, 10m wide and 150m long, I’m told. I am not permitted to see it.

From our partners:

A filmed close-up of the nozzle reveals what looks like a giant icing bag extruding a grainy batter in a careful pattern. This “ink” is made from recycled rubble, fibreglass, steel, cement and binder, and takes 24 hours to dry. The ribbed-finish printed walls are hollow inside apart from a corrugated filler, a design that saves on materials without sacrificing strength. It took eight people one month to finish the £105,000 villa, explains Zheng Jian, general manager of Winsun’s Suzhou operations. If traditional construction methods were used it would take 30 people three months. Costs are halved.

“We’re beginning to set up factories all over the world,” says Ma Yihe, Winsun’s CEO, a couple of days later in the company’s Shanghai office. Winsun Global, a joint venture with an American financial firm who’s identity Ma will not reveal (“they have great influence in the Middle East”), aims to establish 3D printer plants in 20 countries in the next few years, including Dubai, Britain and France. In China Winsun will build as many as 100 factories.

The Egyptian government, meanwhile, has already signed a deal for 20,000 single-storey dwellings in the desert. Winsun will provide the printer and formula for making “ink” from sand, and the houses will be printed on site.

“The future of Winsun is as a technology company,” Ma says. “We’re turning from a company focused on producing and selling construction materials to a company exporting technology … These houses you see are made by our first-generation printer. We’re now developing generation six.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the plans are not without controversy. When Behrokh Khoshnevis, a pioneer of 3D printing at the University of Southern California, learned of Winsun’s creation of 10 houses in 24 hours, he was shocked. “I’m very upset with this man,” Khoshnevis says on the telephone from his office in Los Angeles, referring to Ma.

According to Khoshnevis, in 2013 Ma visited him at USC to view the professor’s work. Later, Khoshnevis was invited to visit Ma’s company in China: “I went there and [Ma] asked me to show him the consistency of this material, and I showed him all of that. Then he didn’t contact me.”

Khoshnevis says he has spent two decades refining and patenting a 3D-printing technology called Contour Crafting. He claims Winsun’s operations, which are similar, copy his idea: “[Ma] has infringed on my method of corrugated wall structures, claiming he was the guy who has worked on this for many years,” Khoshnevis says. Winsun did not respond to a request for comment on the claims.

Khoshnevis, who is also working with Nasa on 3D-printed lunar structures, has no doubt that in the future, a large portion of cities will be printed. “I think in about five years you are going to see a lot of buildings built in this way,” he says.

“At the dawn of the 21st century about two billion people live in slums. I think this technology is a good solution.

Behrokh Khoshnevis

He hopes the technology will help address a worldwide shortage of low-income housing. “I think it is a shame that at the dawn of the 21st century, about two billion people live in slums,” he says. “I think this technology is a good solution.”

He adds that 3D printing will encourage governments to build affordable homes because of savings in time and cost. A significant difference between traditional construction methods and 3D printing is efficiency. If in the future a London borough wished to build a public housing estate, for instance, they could hire a developer with a 3D printer. The printer would then be delivered to the site along with the construction material and architectural design on a flash drive. “They plug it in, hit a button and the buildings get built,” Khoshnevis says. “The nice thing about it is that we can build beautiful, dignified neighbourhoods – not cookie-cutter, box-like houses.”

Not all architects are convinced that 3D printing is good for architecture as a discipline. Writing in the New Statesman in 2013, Amanda Levete, principal at AL_A, long ago warned against the “creep of an unchecked evangelism around the advent of 3D printing … It may come without economic cost at a small scale but in architecture, if we are not careful, this is at the expense of integrity.”

But according to Adam Kushner, president of D-Shape Enterprises, 3D printing will liberate architecture. To underline the point, Kushner partnered with Italian inventor and engineer Enrico Dini to create a self-financed, 2,400-sq-ft, 3D-printed estate – with swimming pool – in Gardiner, New York.

Dini’s massive D-Shape printer uses sand and a magnesium-based binder to create stone-like structures; it could be used in the restoration of crumbling temples, or to build anything from bridges to public loos. Kushner’s vision is more elaborate and personal: the rounded form of his roof design for the estate mimics the surrounding tree canopy, while the walls resemble local rock formations. Built the traditional way, the estate would cost around $500,000. Kushner aims to spend half of that.

“What I’m going to make is a work of architecture,” Kushner says. “It’s going to speak to a greater series of questions and problems. I can’t answer those questions in any methodology other than 3D printing.” The concave-convex surfaces of Kushner’s design, for instance, would otherwise require the prefabrication of formworks (moulds), the mounting of complicated scaffolding, and manual casting – which are all expensive and slow.

“I think [3D printing] is as fundamental a shift as the elevator was in raising our cities,” Kushner says. “Let’s forget about the act of construction being this difficult, time-consuming, energy-consuming part of our lives. We can build these amazing, beautiful structures and then let’s do other things – let’s go out there and enjoy the world around us.”

This feature is adopted from The Guardian