There’s plenty to learn about where residents travel each day, and with whom they choose to interact.

Inequality and economic segregation are some of the unfortunate potential side effects of any urban revival. As both the middle class and their neighborhoods decline, cities and metro areas can easily split into areas of concentrated advantage and disadvantage. This is especially the case in global superstar cities such as New York and London, which have seen large influxes of the global super-rich and startups alongside the young, talented, and affluent. While it is clear that many global cities are becoming more divided and segregated, we know a lot less about the extent to which distinct social classes living in separate neighborhoods interact with one another.

A new study published in the urban policy journal Cities uses cell phone data to examine some of these patterns of mobility and segregation, specifically in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is one of the world’s leading financial centers, ranking third behind New York and London, and one of the most economically powerful cities, ranking fourth behind New York, London, and Tokyo. It is also one of the densest cities in the world, with an extensive transit system that would seem to imply considerable opportunity for mixing of different classes.

But that is not what the study finds. While the authors describe Hong Kong residents as extremely mobile, they find a city that is terribly segregated not just by where people live, but across many dimensions of how they move around.

From our partners:

Tracking mobility

The study tracks the mobility of over 70 participants every five minutes throughout the day for seven days. Participants also logged any activities or interactions that lasted longer than 30 minutes in a single location. Over 60 percent of the study’s participants were employed, and around 30 percent were students. During the work week, the average participant had to travel nearly five a half miles to their workplace, while 14 percent of participants had to travel more than 12 miles.

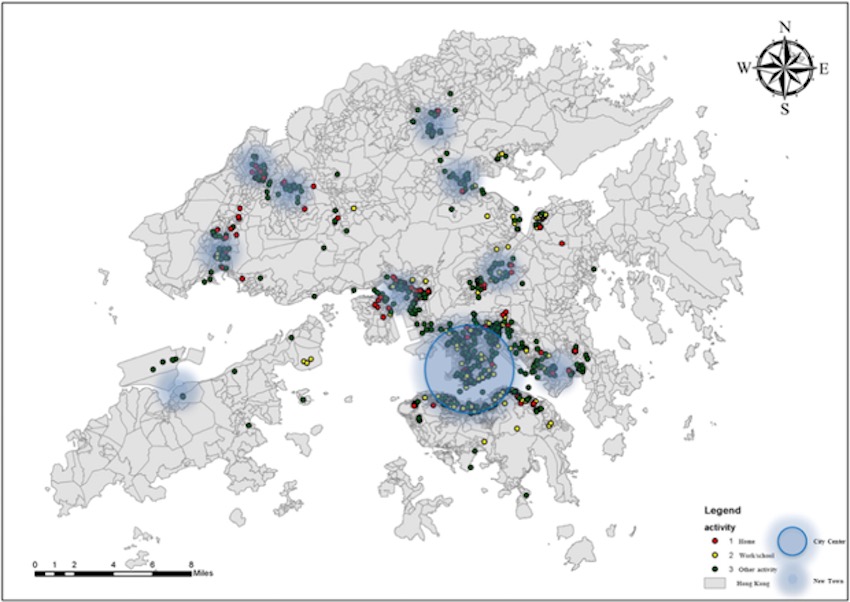

The bulk of the study maps these patterns across neighborhoods (defined as large street blocks with an average of 4,200 residents). Red dots indicate activities that occurred at home, yellow dots signal activities that happened at work or school, and green dots cover the remainder of activities. Notice how the majority of activities occur near the city center (circled in blue), although new suburban areas on the periphery are slowly becoming hubs of activity as well.

The map is littered with green dots, meaning that the majority of activities did not take place at home, work, or school. In fact, the study finds that a whopping 81 percent of participants recorded no activities in their home neighborhood. Put another way, 93 percent of participants were not involved in any sort of entertainment in their home neighborhood, and 96 percent did not visit friends or relatives in their home neighborhood either.

The pattern also differs substantially by age. Younger people (between the ages of 18 and 30) spent the most time in their home neighborhoods (nearly three hours on average), whereas those between 30 and 40 years of age spent far less time near their home (an average of four minutes). While it may seem counterintuitive that young participants are less likely to move outside their neighborhoods, the study suggests that, because many of them are college students, they already have friends in the area and may not feel the need to head out elsewhere. Meanwhile, older residents tend to work longer hours and may often stay near work to socialize or grab a bite to eat.

Mobility is high, but interaction is limited

The most interesting part of the study examines the mobility of three major income groups—poor households (the bottom 30 percent), rich households (the top 30 percent), and middle income households (everything in-between). Here the study finds that, while residents have the option to cross into neighborhoods with different income levels, the tendency is for the rich to conduct their activities in similarly rich neighborhoods. As the authors put it, these residents “may be mobile but interaction with other income groups may be limited.”

To delve deeper into this, the study tracked clusters of activities (e.g. meals, shopping, visits, etc. lasting 30 minutes or longer), and where people traveled to conduct these activities. Altogether, the study tracked a total of 1,073 moves between neighborhoods. Of these, 29 percent of moves were between neighborhoods of the same socio-economic status, with the largest share of participants (38 percent) traveling for shopping or entertainment. Another 32 percent of moves were from rich to less rich neighborhoods (driven largely by meals and other miscellaneous activities) and 39 percent were from poor to richer neighborhoods (mainly for work or to visit friends or family).

This suggests a distinction between income levels that complicates how we think about cities. In contrast to the conventional view of gentrification where affluent people venture into lower income neighborhoods for restaurants and nightlife as a predecessor to actually moving into them, the study finds that affluent people in Hong Kong are much more likely to segregate not just by where they live, but where they shop, eat, and engage in leisure activity. While less advantaged residents also tend to go about their day in poor neighborhoods, they are also active in neighborhoods of a higher socio-economic status. According to Ngai Ming Yip, an author of the study, poorer residents may be drawn to wealthier neighborhoods because of the leisure or retail facilities that these areas have to offer. Many of these facilities, for instance, are located in shopping malls along subway lines in middle-class neighborhoods, making them accessible to the least wealthy. And yet, while poor residents who do move around are likely to cross over into wealthier neighborhoods, their interactions with other income groups are still limited.

At the end of the day, Hong Kong is not only segregated by where people live, but how they go about their daily lives. The advantaged in particular tend to isolate themselves on both counts. This kind of segregation compounds and reproduces class advantage. So long as it persists, Hong Kong’s advantaged residents will not only have more money, but also access to the best schools, networks, and urban amenities, while the poor remain isolated in areas of less opportunity and with fewer prospects for upward mobility.

This feature originally appeared in Citylab.