There are rather a lot of ways, as it turns out.

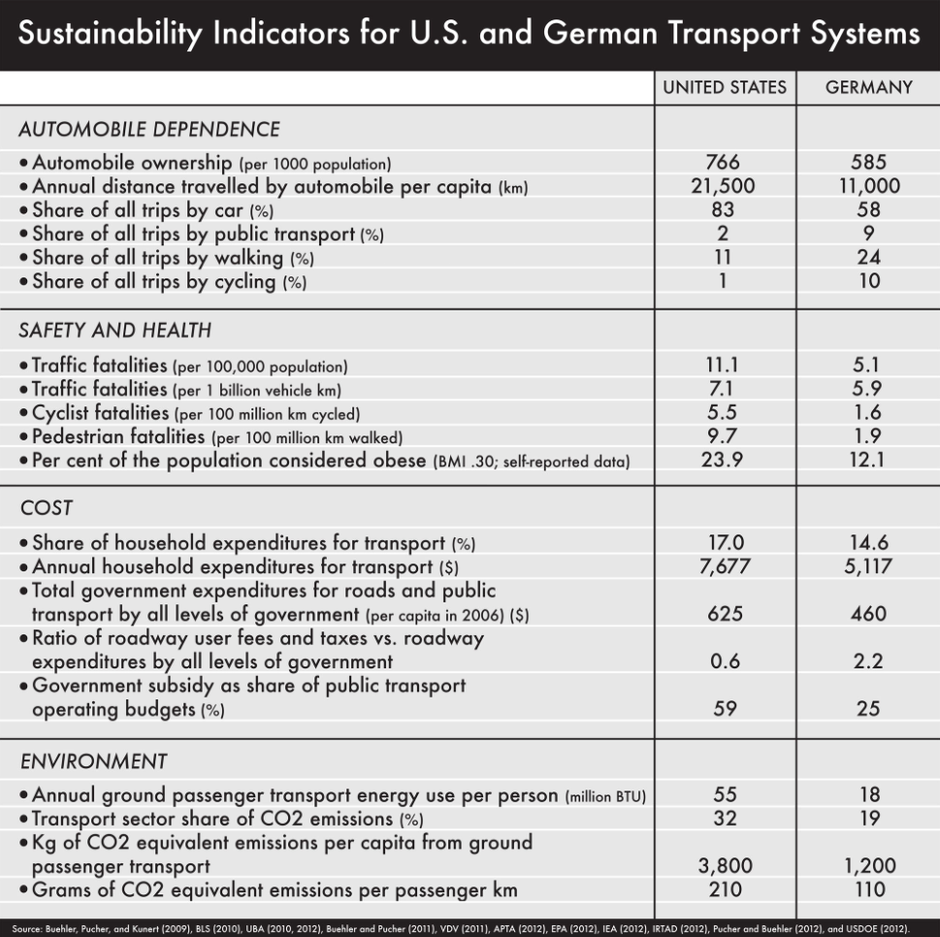

For two Western powers with comparable wealth, democratic governments, legacy car companies, long histories of massive highway investment, and a shared affection for David Hasselhoff, the United States and Germany have followed dramatically different trajectories when it comes to automobile reliance. In the chart below, we list the various ways the countries diverge on driving trends.

All the ways.

Compared to Americans, Germans own fewer cars, drive them shorter distances and less frequently, and walk and cycle and ride transit more often. They have slimmer waistlines to show for their active transport habits and suffer fewer traffic deaths whether in a car or not. They spend less household income on getting around even as they pay much more in driving costs. They use less energy per person on ground transport, resulting in lower carbon emissions.

From our partners:

So yeah. All the ways.

The data come from a recent comparison of German and U.S. planning approaches led by transport scholar Ralph Buehler of Virginia Tech. Drilling down to the city level, Buehler and collaborators find more of the same driving trends in an analysis of two large metros from each country: Washington, D.C., and Stuttgart.

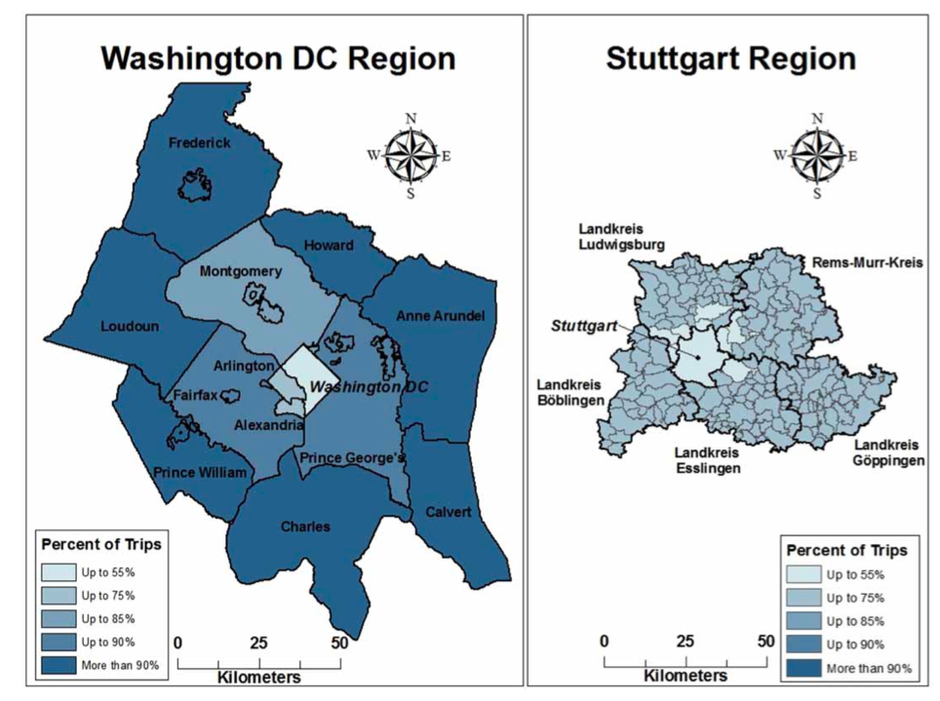

Both areas have similar economies, labor markets, core populations (roughly 600,000 people), regional planning organisations that outline local transport policies. Yet Stuttgart comes off as less car-reliant than D.C. on all sorts of measures. We’ve bulleted some of the highlights:

- Car-ownership (per 1,000 people) — D.C.: 744, Stuttgart: 544

- Share of all trips by car — D.C.: 81%, Stuttgart: 57%

- Centre city share of all trips by car — D.C.: 51%, Stuttgart: 44%

- Suburban share of all trips by car — D.C.: 70-85%, Stuttgart: 60%

- Periphery share of all trips by car — D.C.: 90%, Stuttgart: 70-75%

- Short trips by car (<1.25 miles) — DC: ~66%, Stuttgart: <25%

What’s especially notable here is that driving behaviour in the remote periphery of Stuttgart is about the same as it is in the suburbs of D.C. To wit: the two most car-dependent suburbs of Stuttgart (Nürtingen and Geislingen) have shares of all trips by car roughly equivalent to the two least car-dependent suburbs of D.C. (Arlington and Alexandria): roughly 70 to 75 percent in each place. Meanwhile, walking and cycling account for 6 percent of trips in most D.C. suburbs, while in Stuttgart’s most car-oriented areas these modes still account for more than a fifth of all travel.

So the suburbs of D.C. are basically as car-oriented as the cow pastures of Stuttgart. The map below lays it out pretty clearly:

National policy differences have clearly driven the driving gap. Germany has a tradition of coordinating transportation and land use efforts toward policy goals that stretch across levels of government, such as reducing sprawl, cutting emissions, and promoting public transit. Its narrow zoning laws are better suited to transit-oriented, mixed-use development, and in recent decades it’s made a strong push at the federal level to fund transit initiatives.

The United States, meanwhile, tends to have a more fragmented approach that makes it tough to shift travel behaviour at large. Policy goals are largely local in character and as a result can vary dramatically from place to place within a metro area: Arlington, Virginia, has promoted strong TOD, for instance, while nearby Fairfax County has tended to build parking lots beside rail stations. And while the D.C. metro area has done more than most in the U.S. to integrate fare payment methods across jurisdictions, it’s still nowhere near as uniform asStuttgart.

But with all those differences in mind, Buehler and company did identify two localities in each case that have successfully reduced car-dependency in a similar manner: Arlington’s Rosslyn–Ballston corridor just outside D.C., and Ostfildern’s Scharnhauser Park area in Stuttgart. The researchers point to four development features common to both places:

- Planning goals focused on TOD. Rosslyn-Ballston targeted mixed-use, high-density “bull’s eye” development around metro stations. Scharnhauser Park, meanwhile, required all settlement to be within 1,500 feet of the closest rail stop.

- Long-range plans. Arlington had a massive comprehensive plan to guide the way, while Scharnhauser Park followed a master plan for the corridor.

- Citizen involvement. The “Arlington Way” of public participation promotes “inclusive, accessible, respectful, constructive, persistent, and purposeful dialogue.” Scharnhauser Park has a two-tiered public process for its land use and construction elements.

- Policy coordination. Rosslyn–Ballston planners encourage car alternatives through public transit, bike-ped facilities, and transport demand management programs. Scharnhauser Park does much of the same, with bike- and car-share facilities near rail stops and reduced car parking for residential and commercial development.

Given all the other planning variables across the two countries, these four matching policy elements might offer something of a universal blueprint to reducing car-dependency. Though it’s a blueprint some places need to follow more closely than others.

This article originally appeared in CityLab.