Ambitious architects tend to cluster in the same metropolises: New York, Chicago, L.A. (not to mention Beijing and London). But when they strike out for second-tier cities, it can be a win-win.

A couple of weeks ago, the American Institute of Architects announced which buildings had won its annual honor awards, one of the highest prizes in the field. The real winners, of course, are not the buildings but the architects who designed them. This year the group includes many elite New York firms, plus others from big cities like Boston and San Francisco.

But one of the most talked-about buildings on the list—a modern spin on a barn that serves as a visitor center for a bourbon distillery—is the work of a relatively little-known practice from Kentucky named De Leon and Primmer Architecture Workshop.

The award is no fluke. For years, De Leon and Primmer has been producing great architecture in its home base of Louisville and beyond, racking up regional design awards (and one previous national AIA award, in 2013, for a highly sustainable farm facility). Many of its designs reinterpret the vernacular architecture of Kentucky in the language of modernism, neatly managing to appeal to different tastes.

From our partners:

The thing is, neither of the firm’s founders is from Louisville, or even from Kentucky. They set up shop there as a business decision, one that looks smarter with each passing year.

Roberto De Leon and Ross Primmer met in architecture school at Harvard. It was the early 1990s, and U.S. architecture was in a slump. After graduation, former classmates headed to jobs in Europe and China, but De Leon and Primmer didn’t want to go abroad.

“It was really Ross that initiated this interest in looking at a second-tier city,” says De Leon, who grew up in San Francisco. “To come to a smaller city like Louisville was a little bit of a leap for me.” As the partners explained to Architectural Record in 2010, Louisville stood out because it was poised for growth and transitioning from an industrial to a service economy. It seemed like a place where a small firm could have an impact.

[infobox]Like people in other creative professions, architects cluster, especially the kind of architects who want to take risks in their work. But it would be better if more of them spread out.[/infobox]Without a doubt, the architectural capital of the U.S. is New York City. It has most of the famous studios where young designers want to train and a lot of architecture schools within commuting distance. All of that is attractive to emerging architects, who often supplement their income by teaching. The New York chapter of the AIA is the largest in the country. Like people in other creative professions, architects cluster, especially the kind of architects who want to take risks in their work. But it would be better if more of them spread out.

New York, Boston, Chicago, and other major metros have a lot of construction activity, but also a lot of architects. It’s a competitive field made more so by the sheer number of talented firms in the same handful of cities. That contributes to the culture of stress and overwork that many architects bemoan, some of them—women in particular—even leaving the field in frustration. By contrast, an ambitious architecture practice can carve out a niche for itself in a second-tier city, where the scene is often dominated by “legacy” firms that play it safe.

Access to people of influence is a big factor. In New York or San Francisco, you might be one of many young designers trying to get an in with a property owner or nonprofit board. Go to Louisville, and you can introduce yourself to the right people at a party or a coffee shop. “There are just a lot of opportunities here, in terms of accessibility of people [who] actually are able to make decisions,” De Leon says. In Louisville, “it’s really quite easy to meet the mayor.”

Meet the mayor, and you’re likely to meet the banker, the museum director, and the hospital CEO as well. “Everybody knows each other,” De Leon says. In Louisville and in other cities and towns around the region, his firm has managed to work on a wide scope of projects: museums and visitor centers, private residences, a hospital garden, the headquarters of a mail company. In big metros, architects usually have to specialize to survive; being in Louisville has offered more freedom, De Leon says.

[infobox]”There are just a lot of opportunities here, in terms of accessibility of people [who] actually are able to make decisions,” De Leon says.[/infobox]Some of his architect friends still rib him for locating there, but “Louisville is very adventurous from a design perspective,” he maintains. And it has a much lower cost of living than big cities on the coasts, a draw for new hires (De Leon and Primmer’s two deputies, David Mayo and Lindsey Stoughton, are Louisville transplants too.)

De Leon and Primmer is not unique. It’s one of a number of ambitious architecture firms working in smaller cities off the coasts, offices like El Dorado in Kansas City, Missouri, and those led by Frank Harmon in Raleigh and Antoine Predock in Albuquerque. Several years ago, I visited Omaha and met Randy Brown, an architect who has brought a spare modernism to private homes in that city, but also, unexpectedly, to its bank branches and strip malls (the nicest strip malls I’ve seen anywhere). Brown, too, is a big fish in a small design pond, and he’s left his mark on Omaha.

[infobox]Excellent new architecture is good PR for an aspirational city, especially when it’s homemade, not imported.[/infobox]What’s the benefit to smaller cities of having a Brown or De Leon in their midst? Ease of access goes both ways—developers and officials can call on their local design talent instead of having to look far afield for it (although, De Leon sighs, some clients still assume that New York architects will do a better job). Excellent new architecture is good PR for an aspirational city, especially when it’s homemade, not imported. The local university gets a boost when a rising architect joins the faculty. Residents in need can benefit when local architects perform pro bono services, like designing affordable housing.

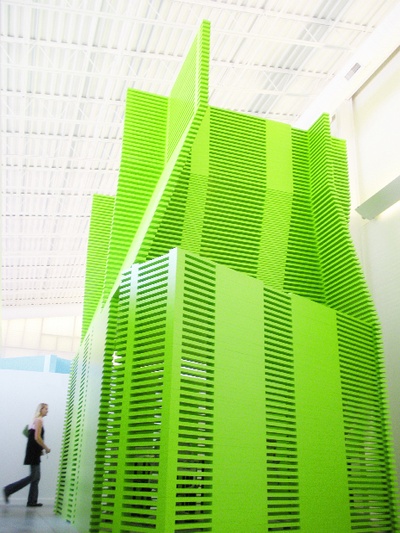

Everyone in a city, though, can enjoy high-quality buildings and public spaces. To worry that people in smaller cities won’t “get” cutting-edge design is wrong. If anything, it can be a selling point: One of Brown’s clients, a podiatry practice, hired him because they liked his own office so much. People in Louisville became so attached to a temporary structure built by De Leon and Primmer that they called the mayor’s office to protest when it was about to be hauled away, De Leon says.

Cities like Nashville, Denver, and Oklahoma City are growing, thanks to an influx of young college graduates and people in search of cheaper housing. Having good new architecture can help attract even more of them—if there are smart designers on hand to create it.

This feature originally appeared in CityLab.