Coasting down from your apartment on your personal bike ramp will be so fun.

The more that bike lanes multiply in cities, from New York to São Paulo, the more people ride. Over the past decade, bike commuting in the U.S. has grown 62%. But it’s still a tiny fraction of overall transportation.

In order to really get people out of cars, a group of Australian designers thinks we need to fully redesign cities—including the way we make buildings.

“The city of the future should not have infrastructure for cycling,” writes Steven Fleming, an urban design professor and director of Cycle Space, an organisation that reimagines bike-based urban design. “It should be infrastructure for cycling.”

From our partners:

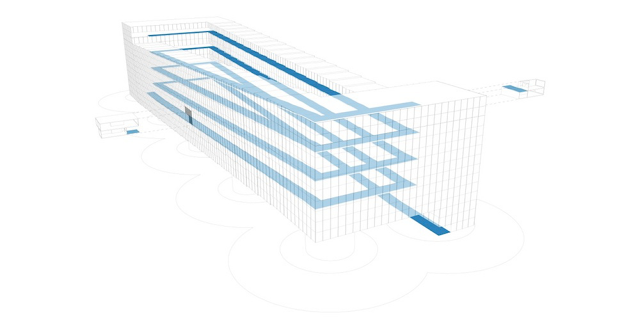

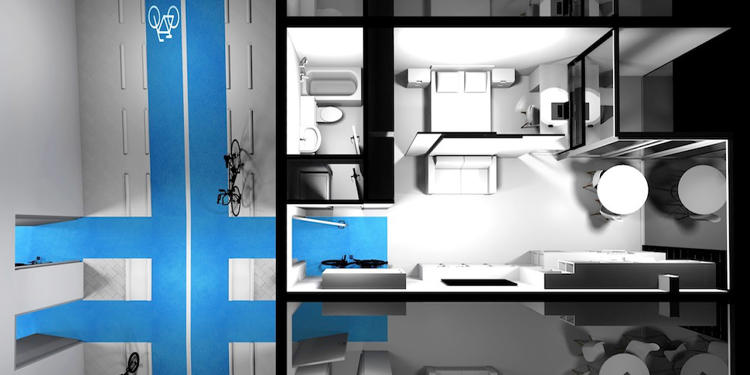

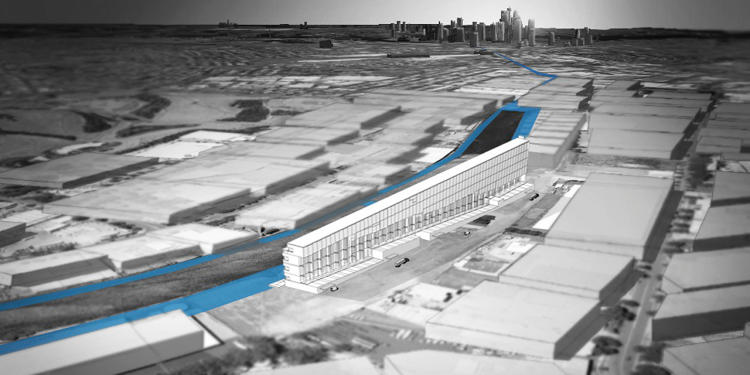

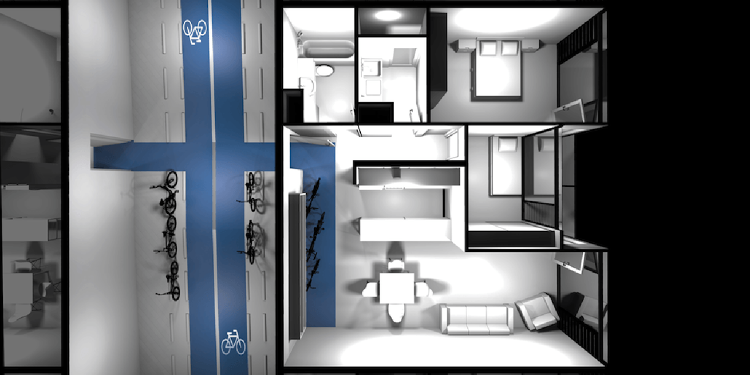

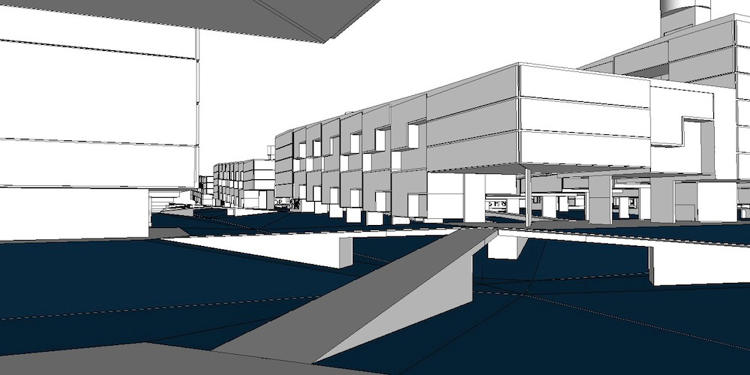

In Sydney, the designers looked at how the city could be rebuilt with a new network of lanes—including a bike-friendly apartment building in the center, with ramps that lead directly to each floor. Cyclists could take an elevator up to their floor and coast down the ramp into their apartment; when they want to leave, they can coast down several stories of ramps directly into a bike lane. Basically, the network of bike lanes extends into the building itself.

He calls it the “start of trip” problem—even if a city has great bike lanes, if someone doesn’t have a good way to store and access their bike, they may not want to ride. Bike-friendly cities like Copenhagen still struggle with what happens when you get home or arrive at a destination.

“They’ve done the cycle tracks and are now doing more pedestrian bridges,” Fleming says. “There’s no doubt they are leaders. The city’s problem, though, is the lack of . . . housing stock that protects bikes from vandals and thieves.”

Done right, he says, architecture would have space for people to store bike in their kitchen, and maybe even wheel their bike through stores as they shop, with a sleeping baby in the bike carrier, or use the basket to hold groceries. “Bicycletecture, as I like to call it, would do more for families than the ‘carchitecture’ they can get in the suburbs,” he says. “They could raise their babies, work, shop, and exercise more efficiently.”

The designers’ mockup for Sydney also incorporates a distribution center at the bottom of the bikeable apartment building, based on the idea that if the city has a good bike network, it can actually be faster to deliver your latest Amazon order on the back of a cargo bike rather than on a van.

“Bike lanes would also be redesigned, with covers that protect cyclists from rain, snow, or sunburn, so they can ride in any weather.”

“Since ancient times, urban mobility has gone undercover,” Fleming says. “Motorists and patrons of public transport have their carriages’ roofs. Pedestrians have awnings and colonnades—or did have, before traffic engineers intervened. I don’t see why cycling should be the exception to an eternal rule of urban design, and instead celebrate Gore-Tex and sunscreen.”

Traffic systems can be redesigned for bikes as well; Fleming points out that if cyclists didn’t have to stop for cars at traffic lights, they could often run errands faster than someone driving in heavy traffic. “This is one of those neat revelations like finding it’s faster making dinner with a chopping board and a knife than a food processor,” he says.

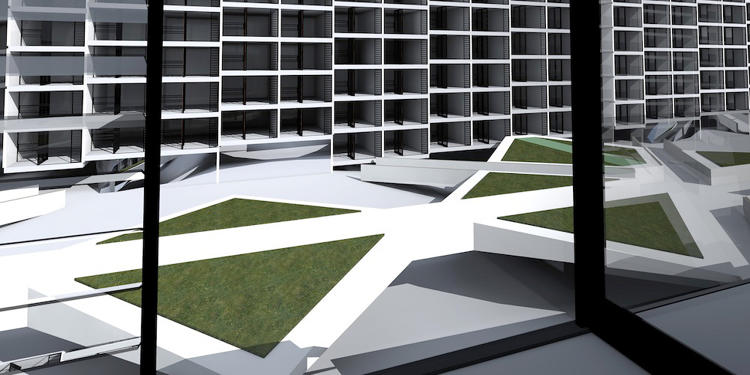

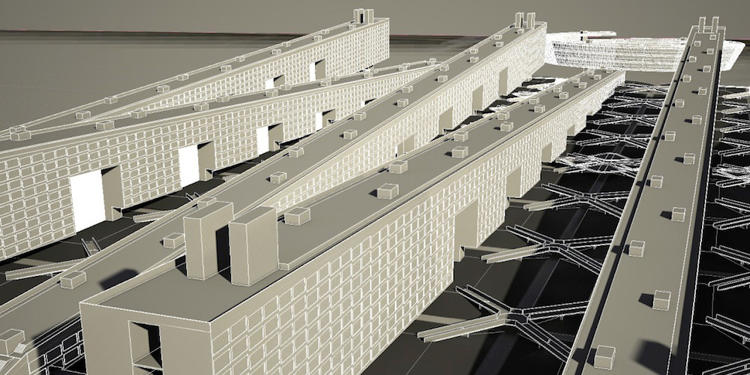

In another set of sketches, the designers lay out what a full “Velotopia” might look like. On the streets, everyone would use a bike, from police to taxis. Heavier electric bikes would handle deliveries. Buildings are spanned by pedestrian bridges, while bikes can fly down dedicated lanes and up ramps into shops or offices. All of the buildings have built-in bike lanes to reach each floor, and could be topped with parks or urban farms.

Fleming hopes it’s the kind of grand vision for cycling that can help lead to bigger changes, just like older visions for other forms of transport.

“The car has Wright’s Broadacre and all of those 1930s avant-garde visions,” he says. “Public transport has Howard’s plan of the ideal garden city. Walking has the European old town as its hero. If the city were a football field, then those three town planning paradigms are being played all at once, like separate games of soccer, gridiron, and rugby—the messy vitality we love about cities. Academia gave me the time and the freedom to devise a fourth code.”

Now he’s hoping that cities take the ideas and start to use them. He’s been testing the designs in the real world already, and says they are designed to meet the world’s toughest building codes. “So yes, this is 100% real,” he says.

This feature originally appeared in FastCoExist.