Even church archivists don’t know what mysteries lie hidden in the Vatican Secret Archives, since many of its documents have never been transcribed. A machine-vision system for medieval text is about to change that.

The Vatican Secret Archives are the stuff of legend. Reportedly filling some 85 kilometers of shelving in Vatican City, they contain the private letters and other documents of past popes, some of them dating back to the eighth century.

The archives are closely guarded. Since 1881, though, scholars have had limited access to some of the documents, and even this has revealed much.

For example, there’s a 60-meter scroll detailing the trials of the Knights Templar, which started in 1307 and lasted several years. There are letters to various popes from Michelangelo; from Henry VIII, requesting a marriage annulment; and from Mary, Queen of Scots, begging for intercession before her beheading.

From our partners:

The archives also contain more recent correspondence, such as letters from Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis attempting to persuade Pope Pius IX to favor the Union and the Confederacy, respectively. Then there are the records relating to Pope Pius XII and his dealings with the Nazi regime during World War II, which have never been published. Indeed, all records from 1939 onward are entirely secret.

While publication of the records is forbidden, the archives have their own photographic and conservation studios. And like many historic archives around the world, they have begun to save images of certain documents to preserve them and allow further study.

But the Vatican’s records are so voluminous that transcribing them by hand is impractical in any reasonable period of time. Could machine vision help?

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Donatella Firmani at Roma Tre University in Italy and a few colleagues. These folks have begun a project called In Codice Ratio (Latin for “The Code System”), which aims to automatically transcribe a part of the Vatican Secret Archives called the Vatican Registers.

This corpus consists of more than 18,000 pages of official 13th-century correspondence between the Catholic Church and kings, queens, and political and religious institutions across Europe. “Never having been transcribed in the past, these documents are of unprecedented historical relevance,” say Firmani and co.

Medieval texts pose a unique problem for machine vision. Conventional optical character recognition algorithms do not work well, because the manuscripts are written in varying styles with different ligatures (characters that combine adjacent letters) and with idiosyncratic abbreviations.

To get around that, scholars have developed machine vision systems that recognize entire words rather than letters. But this is far from satisfactory, because most words appear only a few times even in long documents. So creating data sets for machines to learn from is hard.

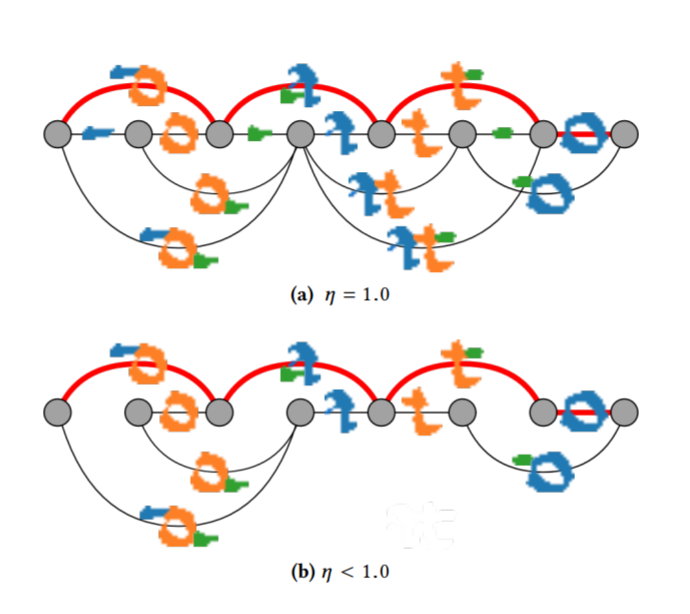

Now Firmani and co have come up with a new way to train an optical character recognition system that divides each word into a series of strokes, which fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. “Our goal is to develop a full-fledged system that transcribes as much as possible from the manuscripts,” they say.

Having divided each word into strokes, the system attempts to fit them together to form known letters and then analyzes all potential permutations of letters. Finally, it rules out all those that are non-grammatical.

For example, a common pattern of strokes can be interpreted as “iii” or as “m,” but the former can be ruled out as grammatically inadmissible. The same strokes might also represent “in” or “ni,” and to decide between them, the system must study the word and its context more closely.

Firmani and co’s first step was to create a data set to train a machine-vision system based on a neural network. This data set must be labeled so that the system can learn what letters are represented by different combinations of strokes.

Firmani and co used crowdsourcing to complete this annotation. They presented the jigsaw segmentation of words as a pattern recognition problem to 120 high school students, rather like Captcha puzzles. The students together manually labeled a 15,000-character training data set in a couple of hours.

The results are impressive. “We were able to generate the exact transcription for 65 percent of the word images of our dataset,” say Firmani and co.

That’s an important step forward for medieval text transcription and for historians in general. However, there is more work ahead. For example, the transcription works with lowercase letters, so an important next goal is to extend the vocabulary to include uppercase letters and some of the many abbreviations used in medieval text.

Just how the Vatican Secret Archives will use this technology isn’t yet clear. Nor is it known whether the Vatican Registers will be published when they are transcribed.

But even if they aren’t, the tools that Firmani and co are developing should allow scholars to make progress. For instance, they allow a data-driven study of historical documents that could look at word or phrase frequencies, for example, and how they change over time. That can provide important cultural insights.

It will be fascinating to see whether the Vatican decides to share this knowledge—or hide it.

This feature is from MIT Technology Review.