Cities reverberate through history as centres of civilisation. Ur. Babylon. Rome. Baghdad. Tenochtitlan. Beijing. Paris. London. New York. As pivotal as cities have been for our art and culture, our commerce and trade, our science and technology, our wars and peace, it turns out that cities might have been even more important than we had suspected, influencing our very genes and evolution.

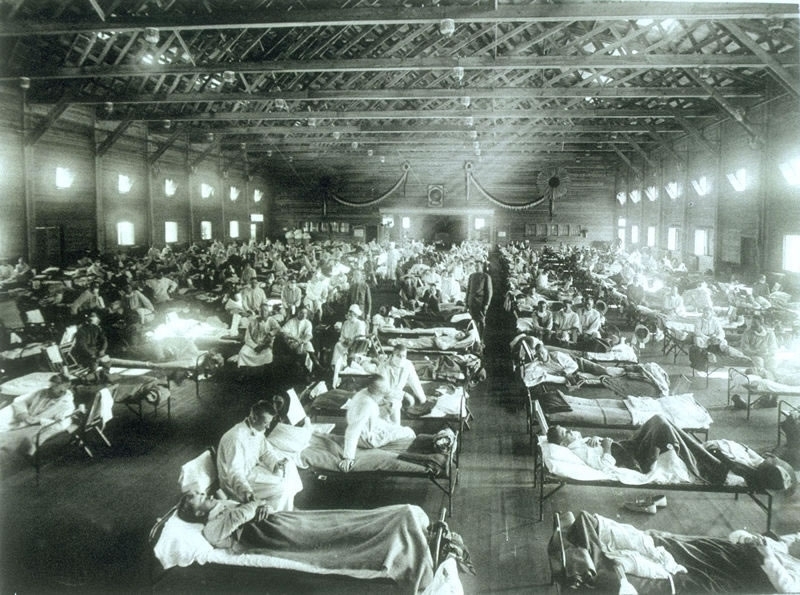

Cities have been painted as hives of scum and villainy, dens of filth and squalor, with unsafe water, bad sanitation, industrial pollution and overcrowded neighbourhoods. It turns out that by bringing people closer together and spreading disease, cities might increase the chance that, over time, the descendants of survivors could resist infections.

Evolutionary biologist Ian Barnes at the University of London and his colleagues focused on a genetic variant with the alphabet-soup name of SLC11A1 1729+55del4. This variant is linked with natural resistance to germs that dwell within cells, such as tuberculosis and leprosy.

The scientists analysed DNA samples from 17 modern populations that had occupied their cities for various lengths of time. The cities ranged from Çatalhöyük in Turkey, settled in roughly 6000 B.C., to Juba in Sudan, settled in the 20th century.

The researchers discovered an apparently highly significant link between the occurrence of this genetic variant and the duration of urban settlement. People from a long-populated urban area often seemed better adapted to resisting these specific types of infections — for instance, those in areas settled for more than 5,200 years, such as Susa in Iran, were almost certain to possess this variant, while in cities settled for only a few hundred years, such as Yakutsk in Siberia, only 70 percent to 80 percent of people would have it.

From our partners:

In other words, urbanisation apparently impacted the human genome, findings detailed online last year in the journal Evolution. This shouldn’t be all that surprising — cities are just like any other niche, and humans who live there adapt to them just like any other species. There is plenty of research into urban evolution, with researchers studying how mice on an urban island adapt to stress (the rat race?), for example, or how fish in the Hudson cope with poisons.

One must be careful, however, of believing the alluring storyline without a good hard look at the evidence — otherwise, it’s just a just-so story. For instance, Barnes and his colleagues do caution that a potential limitation of their study is that in most regions, populations get replaced frequently throughout history. This could mean the people they analysed did not undergo the centuries or millennia of natural selection the researchers assumed they did to pass down this germ-resistant genetic variant.

In a conversation with Barnes, he also noted that other researchers might have problems with the dates for the founding of urban settlement used in his team’s study, which they arrived at by scanning archaeological and historical records. Although these dates can never be totally accurate, Barnes noted they still do not invalidate their results, and he welcomed talks with archaeologists and historians to take the work further.

Paleoanthropologist John Hawks at the University of Wisconsin also found the work interesting. Who knows what other influences cities might have had on evolution, he added — perhaps behavioural changes explaining cultural differences?

This article originally appeared in Scientific American.