For the first 100 years of its existence, the tiny town of Williston, North Dakota, was known for little more than ranching, farming and its proximity to where the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers meet. It was a true frontier town, with a small downtown district and the closest shopping mall some 125 miles away. Blink and you could miss it.

Today Williston—which sits atop the oil-rich Bakken shale formation—is enjoying a second life as a key player in the state’s booming economy. Following several years of record population growth and real estate development, the town will soon boast one more draw: a $500 million retail mecca complete with shopping, a hotel and indoor water park. Not bad for a town of just 32,000 people.

Williston is one of five major projects across the U.S. that highlight the many challenges facing the modern-day shopping mall—from the rise of online buying to Americans’ flight to the cities. But they also identify some possible solutions, whether it’s incorporating elements of what makes that town unique, or weaving in other forms of entertainment.

To critics, investing millions of dollars in a shopping center during the 21st century may seem like a loser’s bet. Since 2010, more than two dozen enclosed malls have shuttered and 75 others are on the brink of failure, according to Green Street Advisors. Other industry calculations estimate that about one-third of the 1,200 enclosed malls built in the U.S. are dead or endangered.

From our partners:

Williston Crossing

- A 219-acre, $500 million shopping mecca with one million square feet of retail and entertainment space

- The town has 32,000 people

- The closest shopping mall is 125 miles away

Much of the blame for these ghost malls is placed on shrinking or dying retail chains—which over expanded through the past decade and lost touch with today’s digitally savvy shoppers. In the first five months of 2015 alone, retailers including RadioShack, Frederick’s of Hollywood and Wet Seal all filed for bankruptcy protection, while Aeropostale, Sears and others shrank their store counts. This left empty storefronts in many malls. “There was a massive amount of building leading up to the financial crisis in the retail sector,” said Suzanne Mulvee, director of research and real estate strategist at CoStar Portfolio Strategy. “Not all of the construction was warranted or economically viable.”

Another headwind for bricks-and-mortar retail is the rise of online shopping, which Forrester Research predicts will account for 10 percent of all U.S. retail sales in 2015, up from 8 percent five years ago. But it’s only one piece of the puzzle. Far more detrimental for a shopping mall, experts agreed, is the arrival of a competing center (which steals customers) and shifting demographics that push supply and demand out of sync.

Consider Cleveland: In 1950, the once-thriving industrial city was home to 915,000 people. As of 2013, its population was half that, and the median household income trailed the national average by $5,000. Just last year the city’s Randall Park Mall—once the world’s largest—was knocked down to make way for an industrial park. “A lot of people want to try and tie it to the Internet or ‘that’s not cool,’ or teens don’t like it,” said Jesse Tron, a spokesman for industry trade group International Council of Shopping Centers. “It’s hard to support large-format retail in those suburban areas when people are trying to just pay their mortgage.”

But balance is being restored in the sector. The amount of new retail space hasn’t topped 40 million feet a year since 2009, according to CBRE, a real estate brokerage firm. This comes after many years with more than 150 million square feet added to the market annually. And now some of the country’s biggest developers are making huge bets that the shopping mall—long a symbol of the American suburbs—still has a bright future; albeit with a major makeover.

Playing the demographics will remain crucial when planning a new mall. Williston’s doubling of population over the past 14 years, for example, was incentive No. 1. Low unemployment and a high median salary only sweetened the deal. But as the new breed of shopping malls is built to satisfy millennials’ changing tastes and expectations, it will no longer look like the stereotypical center of the 1950s.

Among those hoping to woo consumers are Hudson Yards on New York City’s West Side, the largest-ever private real estate project in the U.S., and a $475 million undertaking by Taubman Centers in San Juan, Puerto Rico. All told, $14.5 billion was spent last year on development and redevelopment of shopping centers—the highest level since 2008, and a number that’s expected to increase again in 2015, according to ICSC.

Hudson Yards

- $20 billion project

- Includes more than 17 million square feet of commercial and residential space and a 750-seat public school

- It will house 12 restaurants and more than a dozen shops over seven floors, including Manhattan’s first Neiman Marcus

- Fitness center operator Equinox’s first foray into the luxury hotel business

- Expected to bring in $2,000 a foot in sales each year—about $400 to $500 more than the Time Warner Center in 2014, though TWC has one-fifth the number of shops

Investment also must be made to rejuvenate existing malls, and big money is being ponied up to make these properties succeed. Simon Property Group, the world’s largest real estate company, has redevelopment and expansion projects underway at 24 shopping properties in the U.S. and Asia. In addition to a major overhaul at its World Trade Center location in Lower Manhattan, Westfield’s projects include makeovers for its properties in Los Angeles and San Jose, California. And General Growth Properties, whose strategy is to “acquire assets with significant unrealized growth potential” in U.S. cities, is overhauling its Ala Moana Center in Hawaii, to the tune of $660 million.

“Mall traffic is declining, so you have to give people a reason to go back,” said Gene Spiegelman, a vice chairman at Cushman & Wakefield in Manhattan.

Though the majority of construction is tied to redevelopment, firms are also investing in new properties. Just five months before it cut the ribbon on the Mall of San Juan in March, Taubman Centers opened The Mall at University Town Center in Sarasota, Florida. Triple Five, the developer behind the Mall of America, is moving forward with the much-anticipated (and much-delayed) American Dream Meadowlands megamall in Carlstadt, New Jersey, and recently announced plans to build “the largest entertainment attraction in the world” in Miami-Dade County. Plans for that property include “the world’s largest ski dome” and “the country’s largest water park.”

“The U.S. isn’t overretailed, it’s under-idea-ed. If you have a great idea it doesn’t matter how much competition there is.”

-Bill Taubman, COO of Taubman Centers-

On a smaller scale, bustling city centers are reinventing small communities across the country, giving them the walkable downtowns they never had. In the Southwest, once-forgotten malls have been remodeled and resuscitated to meet the needs of a new set of Hispanic consumers. And outlet centers have continued to flourish, thanks to a new breed of cost-conscious shoppers.

Shopping mall bulls argue that the healthier economy merits high-flying wagers. Shopping center occupancy rates hit a six-year high in 2014, with base rents touching their highest level since the throes of the Great Recession in 2008. At the mall, overall sales productivity—or the sales per square foot—in the U.S. has increased every year, with the exception of during the recession, since the mid-1990s. It’s not enough, however, to rest on these laurels. To succeed, developers and analysts agreed, properties need to offer something consumers can’t get anywhere else—whether it’s bringing a major retailer to town that doesn’t yet have a presence there; a new technology that makes it easier to navigate the mall or find parking; concierge services that deliver shoppers’ packages; or dining and entertainment options that provide a draw to the center on their own.

“The U.S. isn’t overretailed, it’s under-idea-ed,” said Bill Taubman, chief operating officer of Taubman Centers. “If you have a great idea it doesn’t matter how much competition there is.”

One strategy to break away from cookie-cutter properties is to find ways to incorporate a city or neighbourhood’s distinctive culture or history. That was particularly important to the team behind City Point, a development in downtown Brooklyn that will combine retail, office and residential space, plus a dining hall. Anna Castellani, managing partner at the property’s Dekalb Market Hall dining area, said it was crucial to embody the borough’s laid-back and independent attitude through its eateries.

A sense of place

A Brooklyn native, Castellani said dining halls at other retail properties around the city felt too formal, and left consumers angry about how much they’d spent on a sandwich. So when her team got to work and designed City Point’s dining area, they told each of the vendors to bring its own personality to their space. Arepa Lady, for example, got its start making cornmeal flatbreads that are popular in Colombia and selling them out of food truck in Queens. It will continue to sell out of a food cart at City Point. “It can’t feel like it’s anywhere but in Brooklyn,” Castellani said. But it also has to feel effortless, because Brooklynites “can smell it if you’re trying too hard,” she said. “They can smell a rat.”

City Point

- A $1 billion development.

- Includes a 675,000-square-foot retail center, two residential towers and one tower with office, retail and residential space

- Dekalb Market Hall (its dining area) has 26,000 square feet

- Site purchased for $125 million in 2007

- Thanks to a rezoning change that allowed for more development, the site was able to increase rents from $125 to $175 per square foot to $200 to $300

The fusion of shopping, living, office and entertainment space all at one site marks a major shift in retail. In fact, such projects were once considered taboo, as developers doubted consumers would want visit to a grocery store or gym while they shopped for apparel. Today, these mixed-use properties resonate with time-crunched shoppers looking to combine trips—a key tactic driving the Brooklyn project and the $20 billion Hudson Yards megadevelopment.

When completed in 2019, Hudson Yards—the legacy of a failed 2012 Olympic bid—will include condominiums, a public school, restaurants and more than 100 shops, including Manhattan’s first Neiman Marcus. Also, buzzworthy: fitness center operator Equinox’s first foray into the luxury hotel business. “We’ve curated this to make sure when you come in here it’s everything you’d want to have,” said Ken Himmel, president and CEO of Related Cos.

Like City Point, Hudson Yards is striving to feel like it’s a natural part of the neighborhood. That was also the same principle Related followed when it built the Time Warner Center at Manhattan’s iconic Columbus Circle. For that project, the developer worked with marble, granite and a combination of grays and off-whites to give the uptown location an “East Coast, sophisticated vibe” that carried through the feel of the area. It also built the property to seamlessly follow the distinctive curve of Columbus Circle, to make it seem as if it were an extension of the already existing neighborhood. For Hudson Yards, the team wanted to create a different aesthetic. “We wanted to create a DNA for this project that reflected more of the West Side,” Himmel said.

That means a younger, “more gritty” look that incorporates steel and bronze ribbing, to tie in the active railroads running through the area. The development itself required two “platforms” to be built to bridge active railroad tracks. “[We were] trying to set up a framework that retailers would gravitate to because it says something about being on the West Side of Manhattan,” Himmel said. “It’s modern industrial.”

The team at Hudson Yards also plans to host an event each day of the year, giving people a reason to visit the property other than shopping. After it opens in 2018, its six-level culture shed will be home to New York Fashion Week.

Ghost town in the making?

Even the seemingly great retail ideas carry tremendous risks. Signs of what could go wrong are already starting to emerge in Williston, where the steep drop in oil prices has led to layoffs and fewer overtime hours for the town’s energy-dependent workforce.

Shawn Wenko, executive director at Williston Economic Development, estimates about 10,000 jobs have been lost in the Bakken region, an oil-rich area that includes eastern Montana and western North Dakota, since the price of oil started dropping from its highs last summer. Over the past year, the number of active rigs in North Dakota has dipped from an average 173 last May to 79.

“This happens in extraction industries, where something is hot, things rise up and the question is how long does the area stay hot?” asked Craig Johnson, president of Customer Growth Partners. “It might be a year or a decade. Then you’re left with these ghost towns.”

Johnson said it “may make a ton of sense” to develop in an area that’s lacking retail—besides a Wal-Mart, a J.C. Penney and small block of mom-and-pop shops, the town’s closest shopping is more than two hours away, but the town’s economy will need to expand beyond energy jobs for Williston Crossing to succeed.

Such diversification is what makes this period different for Williston than previous years when oil got hot in the area, Wenko said, calling it a transition from a “boom to a business model.” Whereas Williston’s initial population burst came from young men flocking to the region for employment, they’ve now brought their families and are settling down in a more permanent fashion.

This change has led to record-high birthrates and schools that are “bursting to the seams,” said Terry Olin, principal at Swiss real estate firm Stropiq, which is heading up the development, with JLL serving as advisor. The town is currently building its second public high school—to the tune of $56 million—to alleviate the overcrowding, Wenko said.

Developments elsewhere in the town should also help broaden its economy. Last year, Williston cut the ribbon on a $72 million recreation center with an indoor golf simulator, wave rider and basketball courts. A $240 million project is underway to expand the airport and enable larger planes to land. And 20 new restaurants have been added over the past 1½ years, cutting the average wait times from as much as two hours to a few minutes.

Olin was quick to point out that Williston Crossing is a multiyear project, and “oil is notoriously cyclical.” JLL said it doesn’t expect oil prices to impact the project, which also calls for office and residential space, as “the sheer supply [of oil] makes investments sustainable.” Despite concerns about the infrastructure required to support such a massive property, including the police force and water required, Williston Crossing won approval from the Williams County board of commissioners in April. It’s expected to break ground as early as 2016.

As for the properties that are already part of the country’s retail footprint, it’s a tale of winners and losers, with nuances that are easy to miss when looking at national data. While the needle for nationwide vacancy rates stayed within about 2 percentage points over the past few years, the strong properties are getting stronger and the weak are getting weaker, said Andrew Nelson, Colliers International’s chief economist for the USA. According to CoStar’s Mulvee, although the overall vacancy rate for retail properties currently hovers just over 6 percent, that number drops to below 3 percent when stripping out noncompetitive spaces.

Other industry pros point out the original point of the mall has outlived its purpose. Initially developed as a convenient place for consumers to visit multiple stores at a time (not to mention that they were air-conditioned havens during the summer months) its role as time saver has been diminished by the rise of online shopping. Still, there are ways to make even dying properties thrive again—something one California firm has built its reputation on.

Back from the dead

José de Jesús Legaspi, founder and president of The Legaspi Company, started carving out his niche in the Hispanic market 35 years ago by advising retail clients about the best locations for their stores. He was responsible for the original expansion of El Pollo Loco in Los Angeles’ metropolitan areas in the 1980s. Through his namesake company, Legaspi has taken about a dozen dying malls located in Hispanic-rich markets, and transformed them into thriving shopping centers. He does so by first identifying properties that are well-placed—meaning they’re located near a freeway, are accessible and visible—but aren’t taking advantage of the predominantly Hispanic population.

“I remember calling on merchants asking them to come back into the mall when it was 10 percent occupied. They were saying, ‘That mall is dead, don’t call me, lose my number.'”

-José de Jesús Legaspi, founder and president of The Legaspi Company-

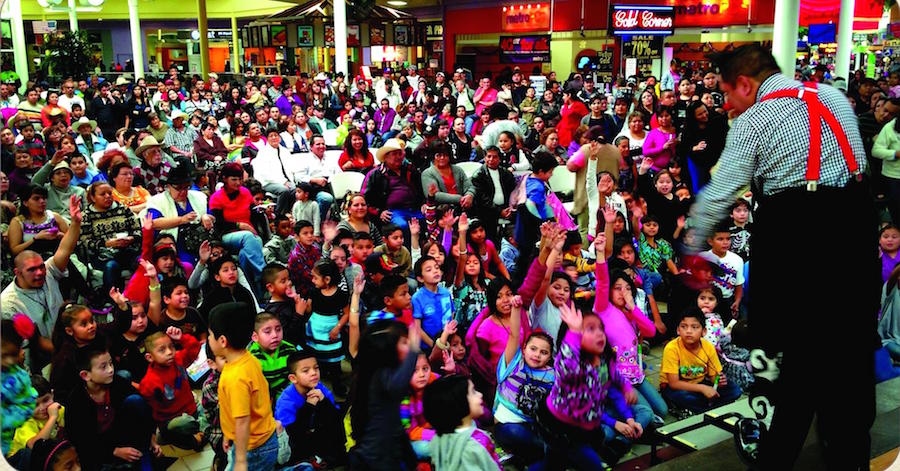

Legaspi then gives the properties a complete overhaul, by painting the walls a brighter hue, and incorporating other elements found at downtown centers in Hispanic countries. That includes bringing in authentic Mexican food, curating the space with shops that cater toward the Hispanic shopper (she tends to be younger and a big purchaser of health and beauty aids), as well as hosting a musical performance each week. “Hispanics still do that,” Legaspi said, referring to their tendency to gather in a public space and listen to live music. “We’ll give you music every Sunday just like you’re used to having music every Sunday, and then make the transaction really incidental.”

La Gran Plaza mall, in Fort Worth, Texas, is one of Legaspi’s greatest success stories. When he acquired the site in 2004, the dying mall formerly known as the Fort Worth Town Center had dipped to a 10 percent occupancy rate. Though Legaspi declined to disclose how much he spent to buy the property, he acknowledged spending three to four times more to revamp it than the firm initially paid. “I remember calling on merchants asking them to come back into the mall when it was 10 percent occupied,” he said. “They were saying, ‘That mall is dead, don’t call me, lose my number.'” Today, the mall is 90 percent occupied and receives about 5 million visitors each year.

Some malls, however, find life as something else altogether. Ellen Dunham-Jones, a professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Architecture and author of the book “Retrofitting Suburbia,” said there are more than 220 malls in various stages of being retrofitted. While about 100 are being made into community-serving buildings, including educational, medical or office space, about 110 others are being redeveloped. Of those 110, about 50 are being turned into the “mixed-use downtowns their communities never had,” she said. ICSC’s Tron pointed to CityCentre in Houston, and Easton Gateway in Columbus, Ohio, as examples of new city centers that are popping up across the U.S., and fuse together shopping, dining and residential buildings.

The locations represent a sea change for the fabric of the U.S., both for retailers and the communities where they were built. Back when the concept of turning a dead mall into a new downtown was first presented to the town of Boca Raton, Florida, in 1998, it was viewed as a “very risky, out-there idea,” Dunham-Jones said. Much of the concern rested on worries that consumers wouldn’t want to replicate the feel of a city in their smaller market. But the new downtown area, known as Mizner Park, has already outlived the mall that it replaced, Dunham-Jones said, adding: “Suddenly, developers began to get interested in this.”

The millennial factor

Build new or redevelop, the success of these properties boils down to one key factor: demographics. When malls began to proliferate in the 1970s, their target shopper was baby boomers, many of whom abandoned cities to live in the suburbs. Things remained mostly unchanged as the small-in-numbers Generation X grew up. But Generation Y—the largest generation in the world’s history, whose members are known as millennials—is spinning traditional retail on its head. “Gen Y comes along, and Gen Y is growing up in the suburbs but is bored to tears with them,” Dunham-Jones said. “They can’t wait to get into the city.

Redevelopment projects are driving much of the spending in retail, particularly in markets that have already proven to have a willing customer base. Manhattan’s Financial District is home to two such properties: Brookfield Place, which reopened in March, and Westfield World Trade Center, whose first shops will open later this year after spending 14 years in the dark.

Brookfield Place, formerly known as the World Financial Center, was headquarters for financial firms including Merrill Lynch and American Express when it first opened in the ’80s. The retail space looked like an afterthought. “[It] definitely had a Gordon Gekko aesthetic to it,” leasing director Ed Hogan said. The original design called for several European piazzas that were connected by zigzag corridors or pathways. “While this is a beautiful European model, it really didn’t allow itself for a successful retail model in the U.S.,” Hogan said.

As part of the revitalisation efforts of the Financial District, which had been left reeling after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Brookfield’s team invested $300 million into the center, doubled the number of shops and gave it a luxurious feel by housing high-end brands including Salvatore Ferragamo and Saks. The company’s hefty investment was justified by the newcomers to the neighbourhood, which doubled in size over the past decade, Hogan said. The area now boasts one of the highest average household incomes in New York City and is a stone’s throw from Tribeca, where the average apartment last year sold for $6 million.

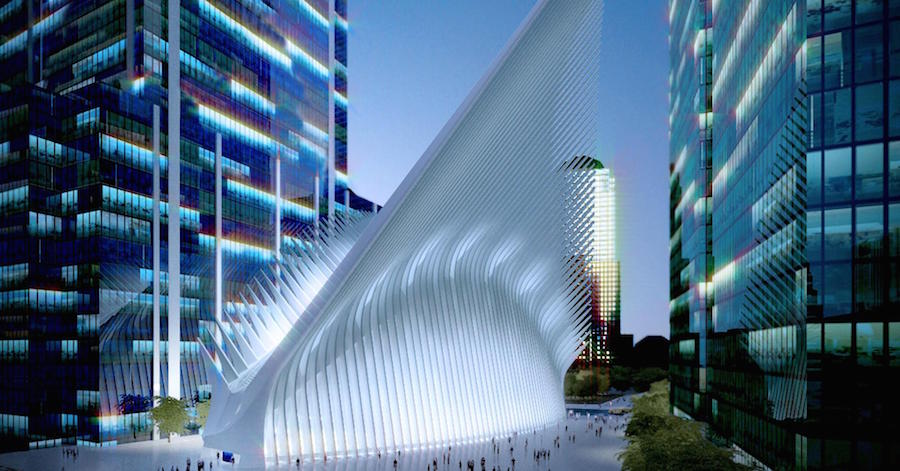

Joining Brookfield Place in Manhattan’s new downtown is Westfield World Trade Center, which has taken on a symbolic role for the neighbourhood, replacing the underground mall at the former Trade Center. Australian shopping center group Westfield acquired a 99-year lease on the mall two months before the Sept. 11 attacks. At that time, the firm already had plans to update the property, and had the rights to expand the retail space. Things took an unexpected turn when two hijacked airplanes flew into the World Trade Center towers in 2001, killing nearly 3,000 people. Damage to the underground mall was extensive and the space—once regarded as one of the most profitable malls in the U.S.—never reopened.

After receiving a face-lift, the property—which Westfield dubs a “retail district”—will relaunch with a decidedly different look. The centerpiece is the architecture of its 160-foot-tall “Oculus,” designed to evoke the image of a dove being released from a child’s hands. Most of the center’s retail will be housed in the multilevel Oculus, which also serves as a transportation hub for the city. Though the retail area is below ground, light shines through the structure’s “wings.” There’s also a retractable skylight that can be opened during the year.

The tenant mix also was reworked. The shops and food options at the former World Trade Center site catered to commuters passing through on weekdays, but now it will be tooled to serve workers, visitors—and most importantly, residents. To meet their needs, there will be a new outpost for the trendy Italian marketplace Eataly as well as Épicerie Boulud, an Upper West Side marketplace that sells charcuterie, breads and artisanal cheeses.

But Westfield World Trade Center won’t be all about New Yorkers. Nearly 4 million visitors a year are expected to come to the site’s three-level observatory. The company declined to offer sales projections for the center, but said it expects it to once again be one of the most productive retail areas in the world.

It’s a safer bet, some analysts said, that Westfield’s investment, which is being made in an already proven market at the site of a national landmark, will be able to meet its goals. As images of failed and abandoned malls spread across the Internet, however, the outlook for other major developments in riskier, frontier markets is less certain.

In the end, timing—and a bit of luck—may make all the difference. When the downtown Brooklyn site for City Point was purchased in 2007, the developers expected two new residential buildings would be built in the area, equaling roughly 500 units. But in the aftermath of a 2004 rezoning that allowed for more development, by the end of last year there were 6,000 units, causing rents to jump. Said Paul Travis, a managing partner of real estate firm Washington Square Partners, “For an old Brooklyn ham like me, it’s sort of unbelievable how that’s all happened.”

This feature originally appeared in CNBC.