Communities like Culver City, California, are focusing on urban forest plans to help protect a major economic and environmental asset: the tree canopy.

To paraphrase a beloved children’s book, trees are nice—they give us oxygen, filter air pollutants, and absorb rainwater. Plus, research shows that trees in urban areas slow down traffic, foster civic pride and identity, and improve property values.

These perks haven’t been lost on officials in Culver City, a neighbourhood in ever-greenifying Los Angeles whose picturesque tree-lined streets are among the most coveted and expensive places to live in the area. Like a growing number of American cities, Culver City is developing an urban forest master plan to ensure the long-term health and sustainability of its tree canopy.

Because of Los Angeles’s size and diverse geography, not to mention a stripped-to-the-bones tree maintenance budget, the city would have a tough time ginning up a unified plan. But incorporated areas of L.A. County like Culver City, a town of roughly five square miles and 40,000 residents, have the freedom to act more nimbly.

From our partners:

“Our trees provide measurable environmental and economic benefits year after year,” says Charles Herbertson, city engineer and director of public works. “It’s hard to imagine this area without the wonderful collection we have. People move here for the old-growth trees.”

At the same time, he says, a large portion of Culver City’s mature trees are reaching the end of their natural lifecycle. This increases the risk of losing many trees at once, especially in areas planted with the same species. The final urban forest master plan, which will be presented to the city council for approval in late 2015, will outline best practices for establishing a diverse canopy with respect to species, age, and pest and disease resistance, and will lay out criteria for adding trees when and where needed.

Culver City’s efforts follow similar moves in nearby Santa Monica as well as in larger cities such as Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and Tampa. Increasingly, cities have recognised that trees provide not only environmental benefits and curb appeal—they’re also good for business.

At Keep Indianapolis Beautiful (KIBI), a nonprofit partnership for creating public spaces, tree-planting initiatives are seen as a vehicle for community development, says David Forsell, president of KIBI. “When we first mapped our canopy in 2006, we noticed that tree cover was lower in areas with higher crime and poverty,” he says.

“So we began adding trees in those hot spots and engaging local residents to care for them, since we’ve noticed there’s a strong correlation between this engagement and higher social cohesion, people acting collectively on their own behalf. In planting more trees, we hope to set these areas up for success.”

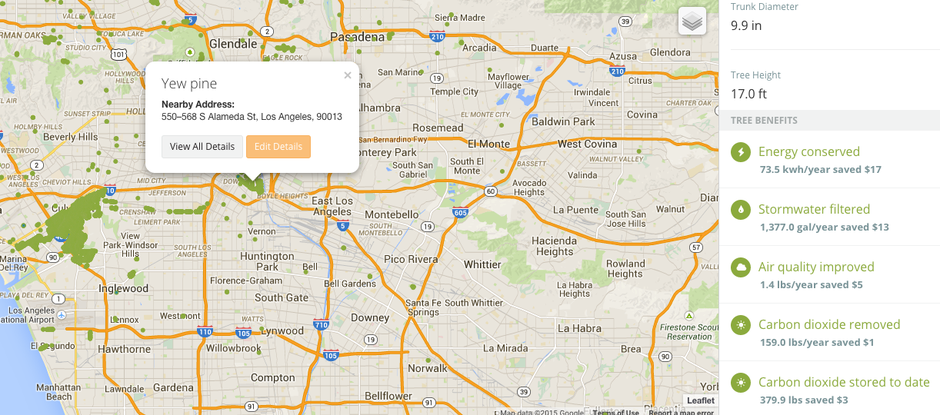

The uptick in urban forest planning has also been enabled by advances in technology that permit faster and easier analyses of tree data. The geographic information system (GIS)-enabled software program i-Tree, developed by the U.S. Forest Service in 2006 and upgraded in mid-2014, uses algorithms to calculate the dollar value of tree canopies and to assess future planting strategies; many other tools have followed.

“Mapping exercises are incredibly useful for urban forestry,” says Pamela Palmer, a landscape architect and president of Artecho, the design firm that’s working with Culver City on its plan. “They help us fine-tune which trees to plant where and identify areas where a change in planting strategy is needed.” Herbertson adds that easy-to-read maps and charts generated from Culver City’s tree inventory have been effective tools for generating public interest and feedback, and believes they’ll encourage buy-in and approval from the city council.

For tree gawkers, the collaborative effort TreeMapLA has put together an interactive map covering many areas of the county, a useful tool that lets you find your favourite local species or finger the nuisance one that drops sticky berries onto your freshly washed vehicle every January.

Though Culver City makes up a mere one-one thousandth of L.A. County’s land area, eco-minded Angelenos are glad for any initiative that chips away at the city’s oversimplified and undeserved reputation as a wasteland of tract houses and strip malls connected by freeways. Plus, there’s a case to be made that as a city’s trees go, so goes the vitality of that city.

A 2012 study showed that some four million urban trees in the U.S. are lost each year to development and natural causes, while impervious areas (read: pavement and buildings) are on the rise, a one-two punch leading to downers like more stormwater runoff and higher temperatures from the urban heat-island effect.

The solution is local action, says Sarah Anderson of the Washington-based advocacy group Alliance for Community Trees. “Most national forestry resources today are diverted to mitigating disasters like forest fires,” she says. “So collectively, cities and grassroots organizations must take up the slack, and they can have a huge impact by investing in their tree canopies. But there’s no one-size-fits-all approach—each place has different needs.”

In other words, think globally, plant locally.

This article originally appeared in CityLab.