Reservoir creating. Electricity producing. Flood preventing. To tweak a song title from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “South Pacific,” there is nothing like a dam.

In a country where thousands of man-made structures have been erected to impound rivers and other bodies of water, a select few dams have managed to demand the public’s attention. These are game-changing dams, seemingly impossible feats of engineering and innovation that have inspired, intrigued and, in some cases, infuriated, like the famed Hoover Dam, pictured.

These man-made marvels are structures with a myriad of benefits and negative impacts. Just as they are extreme in size and strength, dams can be extreme in their detriment — they are often dangerous, dated and responsible for the destruction of vital natural ecosystems. And dam removal projects — the world’s largest to date, the 2012 demolition of Glines Canyon Dam, was carried out as an ecosystem restoration project on the Elwha River within Washington’s Olympic National Park — are increasing in number.

Negative impacts aside, we’ve rounded up the 10 grandest American dams that are remarkable in their scope, size and historical significance. You’ve been directly impacted by these dams — whether you realize it or not. These are the dams that keep the lights on, irrigate the crops that we eat and create the massive lakes where we frolic on summer vacation. These are the dams that, for better or worse, have helped to shape America.

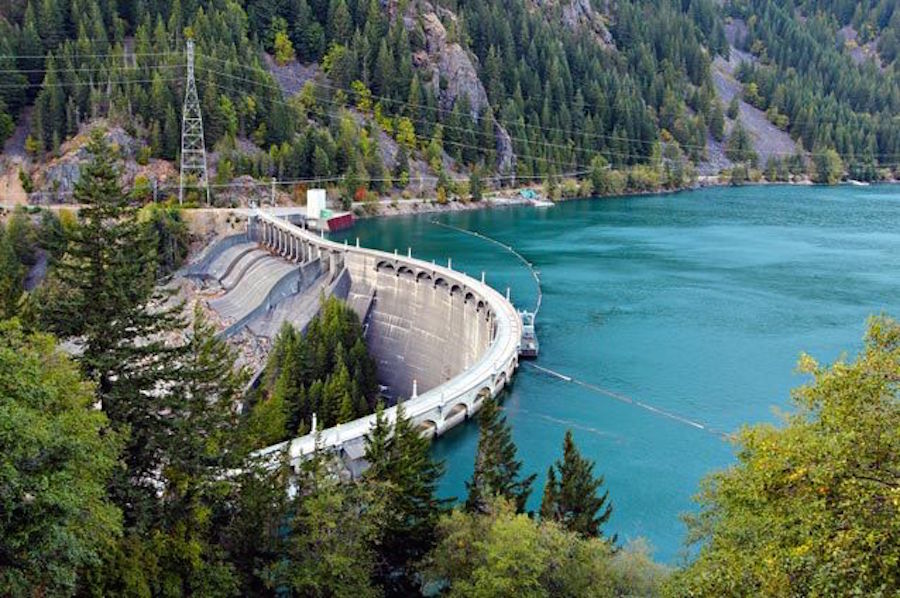

Diablo Dam, Washington

Nestled in the North Cascade range along the upper Skagit River, Diablo Dam isn’t the tallest (Mossyrock Dam), longest-operating (Monroe Street Dam) or most powerful (Grand Coulee Dam) hydroelectric dam in Washington. But when it comes to being enveloped by heavenly natural beauty, this 129-megawatt facility has its peers beat.

From our partners:

When completed in 1936, Diablo Dam — one of three National Register of Historic Places-listed facilities on the Skagit that provide Seattle with a decent chunk of its electricity needs — was the tallest dam in the world at 389 feet. (Today, that honor goes to China’s 1,001-foot-tall Jinping-1 Dam). While dam construction has gone on to reach more dizzying heights, Diablo’s Dam’s reservoir, Diablo Lake, has gotten no less beautiful. Located 1,200 feet above sea level, Diablo Lake, simply put, looks unreal. Traveling down the historic North Cascade Highway, the brilliant turquoise water of the reservoir is impossible to miss — it positively shines. (The crystalline lake’s distinctive jade-green glow comes courtesy of finely ground glacier sentiment suspended in the water).

A hiking and kayaking hot spot during the summer months, the reservoir also can be traversed along the crest of the dam itself on a dizzying, lamppost-studded roadway. It’s a short and somewhat panic-inducing drive but one of the most spectacular in the entire state. The dam’s owner, Seattle City Light, also operates boat tours of the lake itself.

Grand Coulee Dam, Washington

Mountainous and stuffed with mighty rivers, Washington’s rugged landscape is the perfect match for hydropower. And it would only make sense then that the Evergreen State, the top consumer of hydroelectric power in the U.S., is where you’ll find the single largest producer of electricity of any kind in the nation: a facility that generates a staggering 21 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually — enough juice to power 2.3 million households.

Straddling the Columbia River in the heavily agricultural central section of the state, the hulking, history-making renewable energy machine known as the Grand Coulee Dam is more than just grand. It’s positively colossal. When the Bureau of Reclamation opened the dam for business in 1942, there was nothing else quite like it — even today, this man-made marvel remains one of the largest concrete structures in the world. At 550 feet, it’s a couple hundred feet shorter than the Hoover Dam but is an altogether more massive work spanning nearly a mile. In fact, you could wrap a 4-foot-wide sidewalk around the equator twice with the impressive amount of concrete (12 million cubic yards) used to construct it.

Like most monumental dam-building projects, the construction of the fish ladder-less Grand Coulee also came with monumental consequences, including the blockage of migrating salmon. While many might argue the benefits of Grand Coulee Dam do not outweigh the costs from a socio-cultural standpoint, the myriad positive impacts it has had on Washington, and the Pacific Northwest as a whole, are indisputable. Added bonus: mind-blowing nightly laser shows projected onto the face of the dam all summer long.

Ashfork-Bainbridge Steel Dam, Arizona

As you’ll find out further into our abbreviated treasury of water-impounding structures, Arizona is a state with a decent number of major dams: Some are named after presidents (Hoover, Roosevelt and Coolidge Dams); some are supported by buttresses (Bartlett Dam) and some by canyon walls (Glen Canyon Dam); some are more famous for the reservoirs that they form (Parker Dam). And then there’s Ashfork-Bainbridge Steel Dam, a historic Arizona dam that’s in a league of its own.

Completed in 1898 in a far-flung corner of Coconino County, the Ashfork-Bainbridge Steel Dam is, you guessed it, constructed from steel — a wild departure from the concrete and masonry behemoths of the mid-20th century. In fact, the landmark structure, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, was the first steel dam ever realized — and one of only two extant steel dams remaining. There was a third in Montana but it failed just a year after its completion in 1908.

The innovative but modestly sized Ashfork-Bainbridge Dam also differs from a majority of other Arizona dams in that in wasn’t constructed to control river flooding, produce hydroelectricity or to supply nearby farms with water. Rather, the prefabricated-in-Wisconsin steel plate dam was commissioned by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (ASTF) to impound floodwater flowing through Johnson Canyon. Blocked by the curious-looking yet totally revolutionary steel structure, floodwater then drained into a pipe that flowed to a water tower in the nearby town of Ashfork where the ATSF had established a crucial water stop for steam locomotives, which required huge amounts of water. So basically, the dam formed a reservoir in the middle of the Arizona desert that helped power trains.

Fort Peck Dam, Montana

While it doesn’t win awards in the height department, northeast Montana’s mighty Fort Peck Dam remains an impressive feat of Depression-era ingenuity as the largest hydraulically filled dam in the world. Conceived and constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the dam itself isn’t a concrete structure but an artificial embankment formed by pumping sediment from the bottom of the Missouri River and filling it with rock and other materials. Stretching 4 miles across the Missouri, the embankment led to the creation of Fort Peck Lake, a reservoir-cum-recreation hot spot. As the fifth largest man-made lake in the U.S., Fort Peck Lake boasts more coastline (1,520 miles!) than all of California.

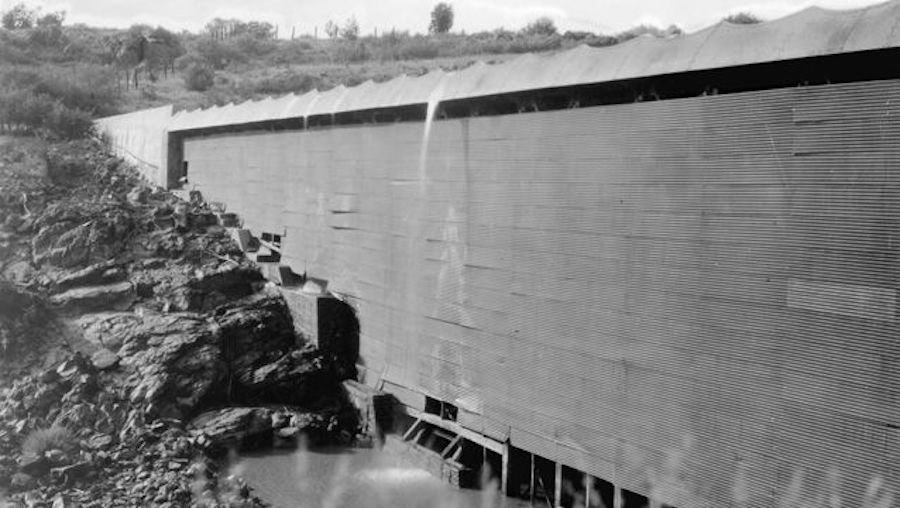

Completed in 1940, Fort Peck Dam started producing hydroelectric power in 1943. Fort Peck Dam’s biggest claim to fame, however, came on Nov. 23, 1936, when a photograph of the dam’s Art Deco spillway (pictured), still under construction, was featured on the cover of the debut issue of Life magazine. Nearly two years later, on Sept. 22 1938, Fort Peck Dam once again made news when the dam failed, killing eight workers in a catastrophic landslide. The bodies of six of those men were never recovered. Today, Fort Peck Interpretive Center, operated as a joint effort between the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is the go-to spot to learn more about the dam’s game-changing construction methods while viewing some grade-A paleontological exhibits.

Buffalo Bill Dam, Wyoming

There’s plenty to keep outdoorsy types merrily occupied at Wyoming’s Buffalo Bill State Park: hiking, trout fishing, wind surfing and more. It neighbors Yellowstone National Park, but the main event at this mountain-enveloped hot spot is a man-made one: a colossal structure that predates the foundation of the park by several decades.

Named in honor of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the legendary late 19th century celebrity showman who melded Wild West bravado with social progressivism, Buffalo Bill Dam, at 325 feet, was the tallest dam in the world when completed in 1910 as part of the irrigation-minded Shoshone Project. And while the concrete arch-gravity dam that impounds the Shoshone River has been dwarfed considerably over the years, it’s still very much a sight to behold, a feat of early 20th century engineering that paved the way for other seemingly impossible infrastructure projects. It wasn’t until 1946 that the dam was renamed in honor of Cody.

Centered around the dam’s reservoir, Buffalo Bill State Park was established in 1957, although most of it was flooded and rebuilt following a dam raising project in the early 1990s. The dam was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. Also equipped with three hydroelectric power stations, two of which have been decommissioned, the Bureau of Reclamation-operated dam and its popular visitor center are located just a few miles from Cody, a Buffalo Bill-founded town that functions as a sort of Old West theme park. Visitors will find a cornbread-‘n’-Cesar salad-slinging cowboy dinner theater, a firearms museum and a rodeo held every single night.

Hoover Dam, Arizona/Nevada

The state-straddling grand dame of North American dams, Hoover Dam — née Boulder Dam — requires little in the way of introduction. Completed in 1936, this Bureau of Reclamation-operated concrete arch-gravity marvel noted for its impressive height (at 726 feet, it’s the second tallest dam in the U.S. behind California’s Oroville Dam) and Art Deco flourishes serves several functions: It produces hydroelectricity (4.2 billion kilowatt hours annually), tames flooding along the Colorado River and provides both drinking and irrigation water to millions via the formation of Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the U.S. by volume.

The Hoover Dam is also, of course, a top American tourist attraction, especially with Las Vegas day-trippers. Constructed over the span of five years at a cost of $49 million, the 6.6 million-ton structure is just as mind-blowing as the kitsch edifices towering over Sin City — and minus all of headache-inducing neon light. New security measures and the opening of the Hoover Dam Bypass/Mike O’Callaghan-Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge (the second highest bridge in the U.S., pictured) in 2010 have made areas of the dam somewhat less accessible to visitors.

Still, it remains a highly bucket-listed destination with considerable pull, especially for those easily wowed by concrete: The dam along with its power plants and other structures were constructed with 4.36 million cubic yards of the stuff — enough to pave a 16-foot-wide highway from NYC to San Francisco.

Mansfield Dam, Texas

For a state that prides itself on bigness and has more dams than any other state (upwards of 7,000), Texas has very few exceptionally tall dams. Many Texas dams are over 50 feet tall, but none rank among the tallest in the nation.

Spanning a deep canyon, the Colorado River-impounding (not to be confused with the other Colorado River in Arizona) Mansfield Dam is a concrete gravity multitasker and the tallest in Texas at 278 feet. Like many dam projects built during the same era, the purpose of Mansfield Dam, completed in 1941 as the Marshall Ford Dam, is threefold: to control flooding, to store water and to generate a modest amount of hydroelectricity (102 megawatts). The 64-mile-long reservoir created by the dam’s construction, Lake Travis, is the largest and most famous of the Central Texas’ septet of dam-formed Highland Lakes. With opportunities for boating, fishing, camping, zip-lining and, famously, clothes-free recreating at Hippie Hollow Park, this crystalline reservoir, alongside Barton Springs Pool, has long served as an oversized community swimming hole for the city of Austin. And while Mansfield Dam itself can’t complete with Austin’s top tourist-snaring concrete structure, Congress Avenue Bridge, a visit to the Lone Star State’s capital city just isn’t complete without a pilgrimage to the shores of Lake Travis.

Roosevelt Dam, Arizona

Behind every great man-made dam in Arizona lies an even greater man-made lake. This most certainly applies to the huge fishing and boating hot spot of Roosevelt Lake, which was formed by a landmark arch-gravity dam of the same name. At over 22 miles long, it’s the largest reservoir confined entirely within Arizona state lines.

Blocking the Salt River in the northeast section of the state, Roosevelt Dam has somewhat of a misleading name. Given the flurry of noted civic infrastructure works, Hoover Dam included, that were initiated and completed during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, one might assume that the dam, named a National Historic Landmark in 1962 but delisted in 1999 following an extensive reconstruction project, was named in his honor. Completed in 1911 largely for irrigation purposes and (to a lesser extent) hydroelectricity, Arizona’s Roosevelt Dam was actually named after — and dedicated by — FDR’s distant elder cousin, Theodore Roosevelt. And even then, the dam, once the world’s mightiest masonry structure, wasn’t even bestowed with its current moniker until 1959.

Adding to the confusion is Roosevelt Lake in Washington state, a reservoir-cum-outdoor recreation destination formed by the Columbia River-impounding Grand Coulee Dam constructed during the FDR era. What’s more, Roosevelt Lake in Washington, the state’s largest reservoir by surface area, is famed as a houseboating mecca as is Powell Lake, a reservoir — the second largest man-made lake in the country behind Lake Mead — formed by Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona.

Fontana Dam, North Carolina

Towering 480 feet above the Little Tennessee River, the Fontana Dam is something of an anomaly: a huge hydroelectricity facility that’s not located in California, Arizona, Washington or Montana. When completed in 1944 by the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Fontana Dam — like its out-West contemporaries, the soaring structure is a concrete gravity dam — was the fourth-tallest dam in the world. Nowadays, it doesn’t come close to other dams in height, but it remains the tallest dam east of the Rockies.

The Fontana Dam is most famous for its foot traffic: The Appalachian Trail crosses the top of the structure as it enters the southwest section of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The dam, boasting a net dependable capacity of 304 megawatts, is no doubt an impressive work of engineering. However, hikers who have just completed one of the more grueling sections of the legendary 14-state hiking trail are generally more appreciative of the facilities adjacent to the dam than the dam itself. This includes the Fontana Dam Shelter, a relatively deluxe rest area — Flush toilets! Hot showers! — best known by its nickname, the Fontana Hilton.

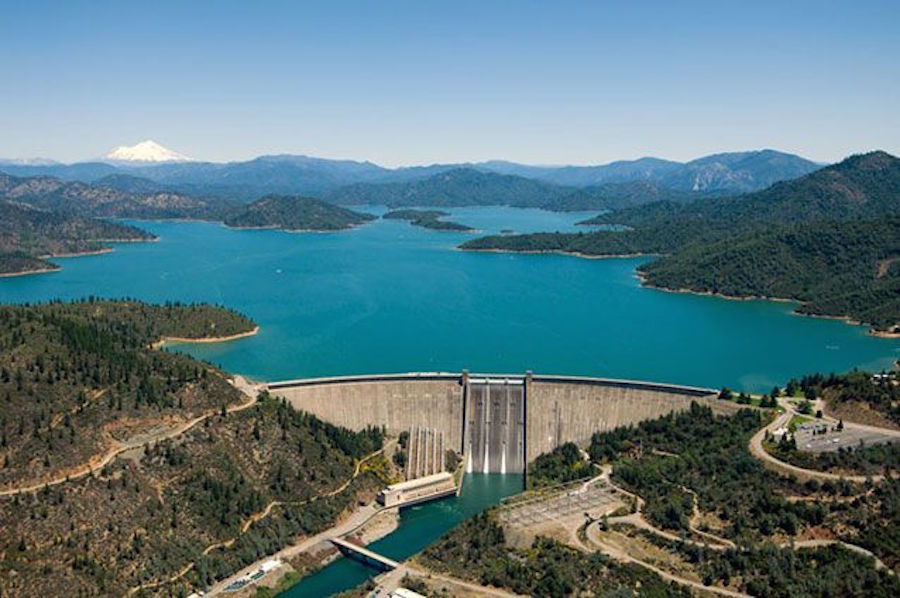

Shasta Dam, California

While no longer the highest dam in California (it currently ranks fourth in the state and eighth in the country), the significance of the 602-foot-tall marvel known as Shasta Dam cannot be underestimated.

Completed in 1945, this Bureau of Reclamation-operated concrete gravity-arch dam that impounds the Sacramento River is one part power generator, one part irrigation machine. This is the dam that created Lake Shasta, California’s largest man-made lake — the immense reservoir that distributes water to the state’s main agricultural region, the Central Valley. So all of those delicious California-grown fruits and veggies you enjoyed with last night’s dinner? You can thank the Shasta Dam for helping make them possible.

While the creation of the 15-million-ton dam generated thousands of jobs and still helps to keep the lights on and agricultural operations in America’s breadbasket well-hydrated, the construction of Shasta Dam, like many other major dam projects, didn’t come without severe consequences, including the destruction of ingenious villages and ecological damage along the Sacramento River.

Although feasible from an engineering standpoint (the dam was originally designed to be roughly 800 feet tall), a $1.1 billion expansion project proposed by the Bureau of Reclamation to increase Lake Shasta’s storage capacity has been met with further controversy. Opponents claim the raising the dam by a proposed 18-and-a-half feet to increase capacity by 14 percent would wreak further havoc on local ecology, destroy sacred native sites and require crucial infrastructure around the reservoir including roads and bridges to be removed and replaces. And in the end, opponents argue that such a massive and potential destructive project — a project not supported by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — wouldn’t produce what the state really needs: more water.

This feature originally appeared in MNN.